Smith provides a brief personal history, then he describes nonviolence training and sit-ins in Nashville. He explains how students came to be a part of this movement, as well as Vanderbilt Divinity School student James Lawson's central role. He tells about the boycotts against downtown stores that came in the wake of the sit-ins. He describes at length the negotiations that finally brought change, noting that southern-bred store and theater owners were often easier to convince than northerners. He describes violence against the demonstrators and the police's role in it. In response to a question by Warren about the dilemma of maintaining black identity on one hand and joining American culture on the other, he advocates being a part of America, not a nation within a nation. He disagrees with Kenneth Clark's charge that the doctrine of nonviolence is psychologically intolerable to the African American. He discusses issues of the participation of northern whites in civil rights work in the South. He talks about the future of black colleges in the face of integration. He feels the church has not taken as large a role in the civil rights movement as it should. He gives his ideas on why so many civil rights leaders came from the South, referring to a "false concept" northerners have of progress in race relations in that section.

Notes:

The first audio tape begins with Warren announcing the end of another interview (with students of Jackson State College); then he announces Smith. The first tape ends with about 50 seconds of silence. The second tape overlaps slightly with the third.

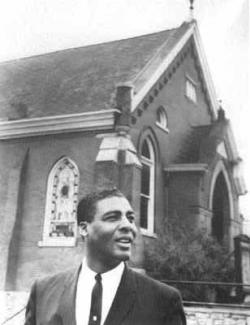

Photo: Vanderbilt University Special Collections.

Audio courtesy of the University of Kentucky.

Kelly Miller Smith

Kelly Miller Smith (1920-1984) was a clergyman and civil rights activist in Nashville. He earned a Bachelor of Divinity degree from Morehouse College and a Master of Divinity degree from Howard University. He came to Nashville's First Colored Baptist Church in 1951, and served as the president of the Nashville chapter of the NAACP. In 1955, he and twelve other African American parents filed a federal lawsuit against segregation in the Nashville public schools. In 1958, he founded the Nashville Christian Leadership Council. He played an important role in the Nashville sit-in movement in the early 1960s. He served as Assistant Dean of Vanderbilt University's Divinity School from 1969 until his death. In 1994, the Jefferson Street bridge in Nashville, Tennessee, was renamed and dedicated to honor the Rev. Kelly Miller Smith.

Transcript

TAPE 1 Searchable Text

Collapse[These digitized texts are based upon 1964 typed transcripts of Robert Penn Warren’s original interviews. Errors in the original transcripts have not been corrected. To ensure accuracy, researchers should consult the audio recordings available on this site.]

Rev. Kelly Smith

Nashville

Feb 13

USE THIS TEXT *

*All text handwritten on single sheet of paper preceding interview with Kelly Smith.

Box 12

(second half of tape)

KELLY SMITH

Nashville

Tape 1

Feb. 13.

[00:00:01] Q: This is conversation with Reverend Kelly Smith, Nashville, Tennessee, First Baptist Church.

[00:00:27] Q: I would like to ask you just something about your personal history for one thing, just for the record. You went to Boston University, didn’t you?

A: No, I did not, went to Howard University, and I did a little work here in Vanderbilt, 1955. Rather early, time, I was among the first four Negroes to attend the University. But well, my grade school days were spent in the state of Mississippi. I was born in the all-Negro town of Mount Bayou, Mississippi, and went to college at Morehouse College, in Atlanta, Georgia, and then to these other schools.

[00:01:20] Q: How long have you had this pastorate?

A: Well, I’ve been here 13 years, 13 years next month, actually.

[00:01:34] Q: Can you remember at what point, and how you became involved in this civil rights effort?

A: Well, I suppose in a sense actually growing up in Mississippi automatically involves one in civil rights efforts, one way or the other. You don’t ignore it, in other words, but I don’t really know where I began to take – I don’t really say leadership but rather aggressive part in some of the efforts being made, I don’t know when that started. I remember as a college student in early forties, being a member of the campus chapter of the N.A.A.C.P.

[00:02:33] Q: Was this at Morehouse?

A: This was at Morehouse, yes. I served a church in Vicksburg, Miss., from ’46 to 1951. And had a Sunday night radio broadcast and all, we had occasion to become involved in some things there, I was on the Executive Committee of that branch of the N.A.A.C.P., and well, then our church, somehow the other, we developed the kind of image, which made people who had some sort of difficulty, racially, feel that if they come there, they can get some form of help. Well, this kind of involvement sort of characterized my staying there in Mississippi, and then when I came here, I got more involved in it, still with the N.A.A.C.P. to start with in leadership, and then forming another organization which is an affiliate with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. And then things went on from there.

[00:03:48] Q: How did the Nashville sit-ins begin? What started it?

A: As I think back on it, it’s interesting, because I don’t think the facts are generally known about Nashville’s involvement in the sit-ins, in relation to the involvement of other communities.

In 1958 when we formed an organization called the Nashville Christian Leadership Council. We had been in existence a very short time before we adopted the methodology of nonviolence. The organization was formed in January ’58 and in March of ’58, we had a workshop on nonviolence, that soon, and then we had them off and on, for some 15 or 18 months.

[00:04:49] Q: Were these the clinics?

A: Yes, yes, sort of clinics, that’s right, and we had many Sunday night coffee sessions. At this time it was all adults, there were no students involved anywhere, and the thought of students hadn’t really entered our minds at that time. At these coffee sessions we discussed the problems of Nashville, and which problems we could perhaps best approach. And having adopted the nonviolent methodology, we had to think in terms of a kind of project which would lend itself to a nonviolent demonstration, which could also serve as an opening wedge for other things. It was after a good deal of discussion that we, independent of any other community, arrived at the matter of lunch counters. This is an interesting coincidence. We had decided this, and in 1959, we went to some merchants here, some businessmen here, and attempted to negotiate with them on the matter of opening up their lunch counters, desegregating their restrooms, and employing Negroes in white collar, blue collar positions. Well, of course, this was considered all utterly ridiculous in 1959; in some instances, people that we went to see, felt, you know, that this was just sort of a frivolous thing, that you couldn’t really be serious about, you must be kidding us. But after having been told what the policy was, and having been told that they would not change, in the fall of ’59, we had kind of staged what we call, well, kind of a pre-sit-in sit-in, it was not really a prolonged sit-in, it was a testing kind of thing, where we had gotten the verbal answer from the merchants. We had gotten the verbal answers that the place was closed to us, but we wanted to find the answer in an “action” situation, for it is possible, we felt, that people might say their place is not open, while maybe they would serve us, maybe they don’t admit. I have known situations like this. So we had a cross section of people, some Negro ministers, some white workers, and some foreign persons, to go down to one of the department stores, and attempt to be served. This was in the fall of 1959. And of course they were refused and had a very interesting discussion with the floor walker there.

[00:07:44] Q: How was that, what passed between them?

A: It was a kind sort of thing, interestingly enough, one thing that we remembered straight through the struggle, was that the floor walker said then that – “if you people wanted to you can change this policy.”

[00:08:04] Q: He said that to you.

A: Yes, he said it to the group.

[00:08:04] Q: Were you in that group?

A: I was not in that group. No. I was not in that particular group. But, and then, from there, it became clear what we were going to have to do, so then we followed intensified workshop training, and Jim Lawson, I imagine you’ll be seeing him.

[00:08:26] Q: I’m going to see him, I want to.

A: Well, Jim was extremely important to us, in what happened here, because Jim was really the only person who was not a neophyte in this matter of nonviolence. He lived it and breathed it, it was his true philosophy, he had spent some time in India and so forth. Jim had come in town just a little after we formed the organization. He had come to live here, so we made him projects director, Chairman of the Projects Committee, and as such, his committee would select the projects, and put them to the group.

[00:09:04] Q: Was he at Vanderbilt at that time?

A: He was at Vanderbilt, yes, he was at Vanderbilt at that time, because I think that was really his mission in town here. So the Projects Committee was conducting the workshops, well, Jim actually conducted them for the committee. Jim came to me one time, and, as I was President of the organization, and asked – what about getting some students to become involved in this? I told him I thought it would be a very good idea. And so he did. The students, and the thing that surprised us, I suppose we shouldn’t have been surprised, but we had no precedence upon which to depend, so that the students became very interested and outnumbered the adults, quickly and easily, and became part of the workshop, and the sit-ins, actually became a student affair, there were so many many here.

[00:10:09] Q: Did you meet any resistance on this, about the recruitment of students?

A: Not at that point, no.

[00:10:14] Q: I mean, not from parents, or from authorities of any kind?

A: No, not at this stage. Later on, we did, once the battle got sort of hot, you see. Then there were parents, there were school officials who felt that we were culprits for doing this. But now we recruited students for workshops, we never recruited anybody for actual participation. These were always volunteers, they had to be volunteers. For one thing, we would not like to have the responsibility of this. For another thing, we believe that a person conducts himself better, if it is something that he wants to do, rather than sort of being talked into, or almost forced into doing so. For the actual participation, this was purely a voluntary matter. And this was something we had to say over and over and over again, because there were teachers, college teachers, and parents, who gave us a pretty bad time, because they felt that we were pushing the kids out there, to get arrested and all this. They just didn’t know that the kids insisted upon doing this. So this is really the background of this, and of course, it was in February I believe of 1960, when we had our first sit-in. The first real trouble came the latter part of February of 1960, when we had violence and arrests, and everything, and the whole community, sort of found itself involved without really planning it.

[00:11:58] Q: The boycott began at what time.

A: The boycott began, I suppose, in about less than a month or something. It almost automatically began, because with all the difficulties, going on downtown, people being arrested and beaten and the hoodlums in the streets and all, people simply stayed away from the stores. We never have found out quite who, started it.

[00:12:24] Q: Started the boycott?

A: The boycott, yes, the official boycott. It was kind of a word of mouth thing.

[00:12:31] Q: I see, spontaneous to begin with.

A: Yes, it really was. What we tried to do, the Nashville Christian Leadership Council, was to give some kind of form and substance, to the boycott, and to try to interpret it in the light of our nonviolent discipline, that is, make it make sense, in this regard and all, and then to, well, to work with it, as best we could, and with the people who were involved in it. And to get maximum mileage out of it. In the pursuit of the goals, of desegregation.

[00:13:09] Q: How did the crack come?

A: The actual change?

[00:13:13] Q: Yes.

A: Well, it was through negotiations.

[00:13:19] Q: Who negotiated, this came different times, different methods of negotiations?

A: Yes, we had to learn, because we made some mistakes in everything, but in negotiation we had to learn that there were certain kinds of people who were not adaptable for this purpose. The Nashville Christian Leadership Council sponsored the negotiations. I was chairman of the group, was chairman of the Negotiations Committee for most of the negotiations sessions we had. Well, we had to frankly see out people who were of the right temperament, as well as determined spirit, to and this isn’t always easy to find.

[00:14:03] Q: For your side.

A: Yes, for our side, we needed somebody who would not “blow his top” so to speak. When something is said that everybody knows is wrong, you say okay, we don’t accept it. But if you become pretty emotional about it, then we would render ourselves useless in going further. So somehow we had to learn that certain people could not be used for this, but could be used in another area. And we finally developed a negotiating team, which worked rather laboriously in this, and this is, well I don’t want to compare aspects of the struggle, but this is an aspect of it that is much more strenuous and significant, than many people seem to think. It’s less dramatic, but it’s a tremendous thing, to sit there with a group of people who come from two entirely different worlds. You don’t speak the same language, and they perhaps have never seen Negroes close up except as janitors and maids, never talked across the table on an equal level, you got to overcome this kind of barrier. So, and then, once you overcome that you must remember that they are part of an economic world about which we know nothing. And to sit there and to try to get together on something is a rough experience. But it was through the negotiations, of course, coupled with the openings that came from the demonstrations that we were able to get the crack in the wall.

[00:15:52] Q: On what spirit did the crack come? Was there any recognition or was it purely a matter of force? Across the table.

A: It was not force in the usual sense of the word. There are differences of opinion about this. I certainly feel that there were people across the negotiations table who were sold on what we were trying to do, on our sincerity. And you see, some of them thought, before hand, I think, that we had horns and that we were all demons, who had come down to destroy their way of life, or something or other. But when they found out we were real live human beings who wanted the same things that they wanted, and had reasons for it, and had talked things out, and who were willing to suffer, sacrifice in order to get this I think this helped. And of course, I think some of the things that we said also helped. Now one of the things we had to learn as negotiators, is that you’ve got to try to, best you can, sit where the other man sits, and try to understand his point of view, even though you don’t agree with him, and this is terribly important. So we tried to do this. In our negotiations we agreed to a control period. A control period is one of thee things: we understand what your problem is. We say: we know that there are segregationist customers who would not like this at all. So let’s have a control period where we would start off with one or two Negroes coming to your counters, at maybe 3 o’clock, something, not a lunch hour, people we have designated, and there will be detectives, plainclothesmen, not uniformed policemen, because that’s too much excitement, but plainclothesmen, sitting there as regular customers. These people will go in, your people will be expected to serve them, then they would go out. You see – this kind of thing, to start with. So we did this for two or three days, it didn’t take a week, I don’t think, really.

[00:18:08] Q: The city government cooperated with this program, putting the detectives in

A: Yes, yes, the city government cooperated

[00:18:13] Q: Mayor was relieved with this solution, you think?

A: I think he really was. I think he was relieved because this was quite a problem to him there, and there had been some things that we had hoped that he would have done, that he didn’t see fit to do, some things that he did, that did not seem to have been the wisest course, to take. And we know that this was pretty upsetting to him and all. I think he was sort of relieved.

[00:18:45] Q: How much of the violence, the brutality, was random and how much was under the aegis of the police force? Or can’t you distinguish?

A: It’s a little difficult to distinguish, because in some instances, the police would seem to sort of give license to this other element that participated. This was not a general thing, there were some fine people on the police force too. Like anything else, we have some of all kinds of people there. And there were some who participated in violence themselves, and others who permitted it. You know. And, of course, always if one of our nonviolent demonstrators would be struck downtown, they would both get hurt, he would get arrested for being struck and the police always called it fighting, and we had many instances where the police claimed that these kids were fighting, when we knew better.

[00:19:56] Q: Were there any convictions of the hoodlums,

A: No.

[00:20:01] Q: No convictions. Any convictions of Negroes for fighting?

A: Yes, yes, and of course, we finally would get cleared, we still have a case, by the way, we have one coming up on the 21stof this month. But oh there were convictions, till we get it up high enough.

[00:20:34] Q: I was interested in what you said about the attitude of the white negotiators, and what bearing it might have on general observations that have been made by a number of people, I mean, a number of Negroes. James Baldwin, said that the southern mob, does not represent the southern white majority. They move in to fill a moral vacuum. Does that make any sense to you?

A: This could very well be true. There are many non-vocal people who are often potentially good people in this thing, if they once would become vocal. And I don’t think the mob does represent this other white man, not necessarily. It represents him in a sense though, it represents him in a permissive kind of sense, because he’s in charge of the police force, he’s in charge of the city and this kind of thing. If these people are permitted to exist, then in many cases, what they do, is awake that. So in that sense, they sort of represent them.

One Page Missing

[00:21:56] Q: It’s an old question of what, whether fascism represented Italy. I was there for the first year of the war, evacuated in June ’40, and I was convinced that fascism did not then represent the will of the Italian people. But it was in a position of authority, over all the country.

A: Yes, yes, this is what happened.

[00:22:22] Q: But now I find this question, I find all sorts of answers, and I know it represents the majority all the way, to those that is simply a question of overall aim, this organized majority who have no point of focus. Now, this is said, in every corner ________ every single spectrum, it’s said, But I think the attitude held must modify the course of action, the person takes.

A: I think so.

[00:22:59] Q: If a person says, and a very able, a lawyer who’s been deep in civil rights, very intelligent and competent man, said here the other day, not in Mississippi either, he said, I’m about to become a Black Muslim.* It’s hard to believe it’s anything but white devil, in answer to this question. Pity that’s one course of action may stem from this. Now he’s affiliated with CORE and yet, he’s active for CORE, but his personal view are getting more and desperately outside of this program. And he admits the feelings now, and these lead to one kind of actions as opposed to what you’re saying.

A: Yes, yes, I can understand. I think I have seen some of this develop. One thing about people here, the feeling that all white people are * “bad”. That there are none upon whom you can really depend, really care.

* “recent” handwritten in margin

There are some people on our board who have said this, the Nashville Christian Leadership Council board, we’ve had this kind thing done, and oh I believe we had one, at least one such person on it since we’ve been organized.

[00:24:32] Q: Mr. Evers yesterday said to me, on this general line of discussion, that one thing he thought was true. That most of the segregationists, not all, but most of them would respect courage, when stood up, ________ peace. And found that the words of most people would stick, once the word was given. You cross a line, and the line would be met in the crossing. And of course, has had a very rough time. Now I, he then talked about the other aspects, other people in ________ but even he ________ had some hope of workable agreements. The word would stick, ________ a lot of them respect courage any way, respect that.

A: I think he’s right. I would go along with it. And I think the courage is expressed in different ways, including nonviolent demonstrations. I think that has met great respect. Well, we have some interesting stories to tell here, like the one of the two boys, one white and one Negro. The white boy had attacked the Negro boy, and going back in the paddy wagon, and the Negro boy talked to him, and before they got to the jail, the white boy was ________ sorry, and he felt guilty and wrong, about what he had done. The Negro boy had not shown any bitterness toward him or anything, and that’s a little bit too much, you know.

[00:26:21] Q: This is a slavery that the man in the mob yearns to be released from the, ________ devil.

A: Yes, yes, I think so. I really do. He may not be aware of it.

[00:26:37] Q: Yes, but he has some inner tension about this, at least, he wants to justify as right, and not just as a piece of offensive violence. Let me ask you another question, sort of leading question, lead where it will ....

THIS IS THE END OF TAPE 1, with Rev. Kelly Smith,

Nashville, resume on tape 2.

CollapseTAPE 2 Searchable Text

Collapse[These digitized texts are based upon 1964 typed transcripts of Robert Penn Warren’s original interviews. Errors in the original transcripts have not been corrected. To ensure accuracy, researchers should consult the audio recordings available on this site.]

Box13,

Kelly Smith

Tape 2.

Feb. 13

THIS IS TAPE TWO, REVEREND KELLY SMITH, NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE

[00:00:23] Q: You were going to say something about negotiations with Nashville businessmen.

A: Yes, there are one or two things about this that are particularly interesting to me, and well, it was, it was particularly startling, sort of. We found out that the southern owners of businesses were, in the final analysis, more easily convinced than the northern owners of businesses.

[00:00:58] Q: You mean, the northern owners in Nashville.

A: In Nashville, that’s right. In the first, well, our first, in the first crack, as you called it, we had six businesses that were opening up. Well, the first to agree, to desegregate were southern owned and operated businesses. We were held up for a full day, waiting for New York, to agree to open up too, because it was kind of a package thing, we agreed that all six would open at the same time. The same thing happened in the case of the theatres. Most of the theatres are owned by a chain in Columbus, Georgia. Martin chain. But we had one that was owned by somebody in New York; where we were able to get the Martin chain to agree, before we were able to get the New York people to agree.

[00:02:00] Q: How do you interpret this?

A: I really don’t know, I really don’t know, I think being absent has something to do with it. Being absentee owners, the fact that they aren’t on the scene, and the other men are. Also I think perhaps they have some false notions about things, I don’t know.

[00:02:30] Q: You mean, they are misinformed about the southern temper, is that it?

A: This is very possible.

[00:02:37] Q: If the absentee ownership is in Georgia, for one thing, that’s the Deep South, and they agreed, is that right?

A: Oh yes, in fact, the president of the chain, chartered a plane, and came for a conference which was held right here, in this office. In the first session he actually agreed to desegregate, the only thing we had to do was to work out how we were going to do it, and include the other theaters and what would be the best way to do and so forth. Yes, they came through first and then they offered their assistance and made kind of a joke out of it, they said, here we are Georgia white people trying to convince New Yorkers that they ought to integrate. Which is what they did. And of course, the others came through.

[00:03:25] Q: What about the hotel situation here? In Nashville, now.

A: Yes, well most of the hotels are open to all people here.

[00:03:37] Q: Which ones are not, at the moment?

A: Let me see, they are the small hotel and I forget which ones they are.

[00:03:46] Q: You mean the big ones are open.

A: The big ones are open. The main hotels and motels.

[00:03:51] Q: Are there any restrictions in the hotel situation?

A: Not since we got them open. This was just a year ago. One of the most recent things, we were able to accomplish. And the hotels were open largely through the Human Relations Committee, appointed by the Mayor. Now we did have some sleep-in demonstrations there, ahead of this.

[00:04:15] Q: How were they organized?

A: The sleep-ins?

[00:04:17] Q: What did they actually do?

A: They went in, they weren’t really sleep-ins, they went in and had lobby sit-ins, that kind of thing, sit in the lobbies, there, and sometimes get arrested, sometimes not get arrested, but just being there, staying there as long as they could.

[00:04:33] Q: But once the Mayor’s committee took action, there was no problem.

A: That’s right, part of it is the fact that a significant chunk of your economic power structure is on the committee. A number of bankers, and this is very important, I think, a very wise move on the part of the Mayor. And so these fellows agree to go after something, then there’s a great deal behind what they say, which the business operators respect.

[00:05:02] Q: It’s not a lecture from the “liberals”, it’s a lecture from the pocketbook.

A: I think this is what happens, yes.

[00:05:10] Q: Let me ask you a more general question, which, I encountered first years ago in a reading Dubois {Du Bois]. I’ll read a brief quote – “The Negro group has long been internally divided by dilemma as to whether striving upward should be strengthening its inner cultural and group bond, and identify, for intrinsic progress and for offensive power against ________, or whether it should lean toward the surrounding American culture.” ________ But the Black Muslims represent one pole in the extreme form, and the other people who pass, Negroes who pass, and disappear. But ________ encounter sometimes the loss of all cultural and nonidentity if you move toward a cultural acceptance. _________ How does this present itself to you and the people whom you are acquainted with?

A: Well, I think most of the people with whom I’m associated and this also represents my own point of view, believe in becoming a part of America. And not a nation within a nation, not a little cultural island of some kind here, but we want to get into what is called the melting pot. America is called a melting pot. And this is what integration is all about. There are some things, I believe, that have been contributions to our culture which have come from Negroes and which would not have come, had it not been the practice of segregation and all this. I think there are some risks that are involved with integration, in other words, but I think that the rewards of integration are worth the risk.

[00:07:15] Q: I was thinking about the sense of regret of the possible loss of identity. Now some southerners feel that, that they have a loyalty to southernism, _________________. A resistance to Americanism. And ________, in the same way, has viewed ________ torn the same way. Become Americans and enter into a totally integrated society, seems the death of some part of the soul. And some do. *

A: Of course, the situation involving the Jew is very different from ours in that there is a religious matter, but I really don’t see any merit to the argument that we ought to retain anything. I simply think whatever we have to offer, we ought to become a part of the whole, let it be melted and let the identity be lost, so far as this, this, -- in fact, I think this has already happened to a great extent. I think it’s a little late to stop it if anybody wanted to.

[00:08:34] Q: Let me tell you briefly one thing. At Howard University, in early November, at the Nonviolent Conference, one of the main speakers, was a young girl who _________ are a lot like mine, Phi Beta Kappa, said she’d been in all the jails. And she rose on the platform, and said, “I have a great joy, I have a discovery. I am black. Now your faces are so and so and so, but your hearts are white, and your minds are white. I am black. You are white. And this brought down the house. The black mystique ________ like a brush fire.

A: Yes, this is interesting. I was supposed to attend that conference, and I couldn’t make it.

* “recent” handwritten in margin

[00:09:27] Q: Well, I was surprised by this, the, by the wild quality of this response, really. I thought there would be more variety. It went through the university of course. The next day is different. Let me ask you another question. As a talking point. This is a quotation from Kr. Kenneth Clarke [Clark], on Dr. King, as opposed to the Muslim philosophy.

“On the surface King’s philosophy appears to affect health and stability, while black nationalism displays pathology and instability. A deeper analysis, however, might reveal that there is also an unrealistic if not pathological basis to King’s doctrine. The natural reaction to injustice is ________ resentment. The form which such bitterness takes, need not be overtly violent, but the corrosion of the human spirit is inevitable. It would seem, therefore, that in the demand that the victims of oppression be required to love those who oppress them, places an intolerable psychological burden among them.”

A: Well, of course, it seems to me that Dr. Clarke [Clark], is and the last part of that quotation, confusing the actual philosophy which King represents, with an inadequate expression of that philosophy. I think that perhaps there is something pathological in some of the expressions of this, on the part of some of the individuals who are adherents to it. But now, as far as placing an intolerable psychological burden upon people to love his enemies, well, this, I don’t know, I’m not a psychologist.

[00:11:41] Q: ________

A: Yes, this is what I’m saying. This is not new at all. In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus Christ says, “Love your enemies, pray for them that despitefully use you, bless them that curse you.” It is impossible, and I frankly think that it is, ( now this is from a layman’s point of view), psychologically healthy. For an individual to do this, difficult, yes. But I think it is highly healthy. I think the absence of this, the inability to do this, may be a greater psychological burden. Certainly feel it would be a greater spiritual burden.

[00:12:33] Q: They can’t really be separated, can they?

A: I don’t see how you really can.

[00:12:37] Q: The psychological and the spiritual.

A: Right.

[00:12:50] Q: We know a good deal about the white man’s stereotype of the Negro, it’s been ________ many times. What about the Negro’s stereotype of the white man?

A: Yes.

[00:13:06] Q: How do you think, how would you describe that stereotype,

A: I think part of it is expressed in the feeling that all white people are bad, as far as the racial problem is concerned. And there are people who definitely believe that. They have had some kinds of experiences, they have observed something, and they use these experiences, to represent everything. They have generalized on something that is a particular specific experience. I don’t know, I don’t think for the moment, how this idea of stereotyping further expresses itself. I think that there are people who think that the attitudes of all white people are alike. There are some who are frank about it, and some who disguise it. Of course, I think this is a very false and wrong kind of thing. I used to have a similar feeling. Of course, I grew up in an isolated kind of community.

[00:14:18] Q: Mound Bayou.

A: Yes. And I didn’t know very much about white people. So whatever I saw of them, I thought that more or less represented all of them. I had this kind of fallacious point of view, too. I remember once, when a mob came to our town. This was the first time I had ever seen that many white people. On any occasion at all. And

[00:14:45] Q: What was the occasion?

A: Well, a Negro farmhand had been shot in the foot by a, I started to say a slave master, that’s about what it amounted to, by the plantation owner, or boss, or somebody, and he returned fire. And while the white man only shot him in the foot, the Negro shot and killed him, and he left, and Mound Bayou being all Negro, was considered, the logical place where a person like that could come. And that had happened, this fellow had been there. He was gone, however. I think he was outside the town but a mob came into town, with, many of them wore hunting clothes, they had guns, they had a rope, about this high off the back of a truck, real large rope, and a barrel of gasoline. All of this, you know, looking for a Negro. It was a kind of sport to them, apparently. Well, word reached us at school, I guess I was maybe 12, 13 years old, or something, and so coming back through to town, I saw these people there, and they had the only doctor there surrounded; they were surrounding him and were asking him questions, and he was, answering the way he wanted to, not the way they wanted him to, and if he would give a wrong answer, they would raise their guns like this, and you would just know that they were going to fire on him. They never did, in fact, he’s still living. He had treated this man, and somebody had told them that the man had been treated by him, and the doctor would not give the facts to the mob, and I don’t blame him. He was morally justified in that situation. Well, these were white people to me, the first time I’d seen this many white people. So I developed a rather distorted notion, it was some years before I came to know white persons on a different kind of basis, and to realize how wrong that I was, and this kind of stereotyping does happen, and I think it’s bad in either case.

[00:17:18] Q: I have been told in Mississippi by several people, that there had been very strong resentment on the part of Negro students and other Negroes who work in the Civil Rights movement, voter registration and so on, against whites, and also against northern Negroes who came in, to work in this too. This had been a real problem in Mississippi. Three different people brought this up, and told me, this is ________ same episodes. But primarily against the younger white people who came in, students, and either just out of college, or just of school, who came, real friction had developed. And real problems had occurred. And real possibilities of a little bit of violence there. Have you seen any of that here in Nashville?

A: Not very much of it. We welcome people who come in from other communities. I can conceive of problems developing, but I cannot conceive of a problem being so acute that it would mean that we need only ourselves, we don’t need meddling outsiders. You see, I think this is just so much brainwashing, I think we have fallen victims of some of the propaganda of the bigots. The meddling outsiders, you know. I was accused of being a northern outsider, until I told them that I was from northern Mississippi. This changed. I can conceive of people going off half-cocked, who come from the north, and who have a very distorted and false notion of what the real problem is, and maybe of their own importance, to the solution, and to come in, and to assume a role that would be harmful, I’m sure that this can happen, and probably has happened.

[00:19:23] Q: Some of it has happened. In some cases I was told, this is because well-trained people, who moved quietly in, in what you might call command posts, not through any will of their own, but because of the need. And this created friction, human nature ________ itself.

A: Yes, yes, can happen.

[00:19:44] Q: But also involved in this, there was something of the white stereotype, that

A: Yes.

[00:19:50] Q: got mixed up with this. ________

A: Yes, and I’m sure this must have been involved.

[00:19:57] Q: As much as I hear, I gather, ________ had been.

A: We have had many people to come in who appear to have genuine interest, but who try to take advantage of this situation. We’ve tried to be alert to this, as nearly as possible, because we know very little something about the people who come in, and we have not always judged them correctly. But this hasn’t really worried us too much because we think that the authorities, federal authorities, understood the situation.

[00:20:39] Q: Of course, it could be used, in some communities, it could be used as a very useful weapon for segregationists.

A: We had one situation here that surprised us that it never hit the press, never really reverberated against us. That was a couple of boys who came in here, a couple of white boys, who came here from some place, and got arrested by the police, and the police found communist literature on them. In their possession. And they had participated in some demonstrations, since they had been here. That never really hurt us, to my knowledge. I don’t quite know why. For I know one thing, I think that the federal authorities, and I underscore federal authorities, were aware of what we were doing, and were aware of some of the problems, in this kind of thing, and therefore no doubt were not too much worried about kids like that.

[00:21:38] Q: Of course, it was exploited even with no basis for it, in Mississippi.

A: Oh yes.

[00:21:41] Q: It was distorted practically the newspapers were turned over to this notion.

A: Yes. Anybody who is for integration is a communist, some people think.

[00:22:01] Q: I remember that Hoover’s appointment in Judge John Parker’s Supreme Court, was opposed by Negroes, and I’ve read that this was the first successful organized political protest on the part of the Negro. Parker was not confirmed in the Senate. He was opposed as a southerner. It appears later that Parker was a quite impartial judge. This same kind of opposition later developed to Judge Black.

A: Yes, I remember that case.

[00:22:47] Q: Do you think that kind of stereotyping of a southern white would occur now in Negro policy?

A: Not as emotionally but I think the question would be raised. Yes, it would be considered an issue, and something to be concerned about. But I don’t think it would be quite as, I don’t think the reactions would be quite as emotional as they were then, because we’ve learned a good deal about southern whites; one thing is that they are individuals, rather than everybody being of the same disposition and set of values.

[00:23:25] Q: Let me switch to another topic just for a moment. It seems that the White Citizens Council people are now running ads with quotes from Lincoln.

A: I saw it yesterday.

[00:23:41] Q: Well, long before that, many people have remembered what Lincoln’s views were. ________ him as a racist. Now, this fact, of his racist attitudes, what does that mean to the Negro now today? Why go to Lincoln’s monument if he is a racist? The march on Washington. What problems are inherent in this simple fact, and what solutions are there for the problems? Emotional problem, you see.

A: I think there’s a good deal of ambivalence, in our attitude toward Lincoln. Of course, when you consider Lincoln against his setting, you might find a different kind of thing, than what you would find if he’s twisted against the setting of the present.

[00:24:44] Q: That’s the question I’m really raising. How much certain judgments are historical, or merely place some abstract notion outside of history. If you ask, say, a not too informed Negro student, the question, you see, well, Lee was an emancipationist, and willingly emancipated long before. * If they, you know, are older, and an older student knows his history, you get one whole body of feeling, from the younger person who’s never know about this _________, another kind of ________ unhistorical answers, you get a violent confusion, ________. I don’t know what, there’s not price tag on this question, I don’t know what you’d say about this question.

A: Yes. Well, that’s one thing that I would try to take into account. The facts of the setting, and of course, the whole setting, against which Lincoln lived, and then the particular context of specific statements which he made. Just a quotation from Lincoln, would not present

[00:26:04] Q: No, a single quotation is not fair.

A: That’s right, no. What he was getting at, you know.

[00:26:11] Q: As one eminent historian said to me, some time back, it would be almost impossible to find a man in Europe or in America, in 1860, who was not * a racist.

* “recent” handwritten in margin

A: Well, this is what I mean.

[00:26:26] Q: You might have found one, but it would be a very long ________ getting at him.

A: Yes, a rare find.

[00:26:31] Q: This question of time, of history, is what I’m coming at now. I’ll read you a quote, if I may. This is from Gordon B. Hancock, Dr. Hancock, you remember: “The color question is a social problem, and as such is not essentially different from any other social problem, and by leave of this fact, can respond to the same _________ of adjustment or maladjustment. Social problems, by their very nature, do not lend themselves to instantaneous and absolute solution.” This over and against the slogan, “Freedom Now,” at two poles of the problem of the Negro movement, the civil rights movement, the Negro ________. The two poles, you know of feeling and discussion. Now can Freedom Now, be interpreted in this context?

A: Well, Freedom Now, I think has to be the goal of anybody who is sincere, in the struggle. I think it has to be, for, I suppose for strategic reasons, you can’t ask for less. Let me give you just one example here. Our ministerial association was an interracial group. I talked with the President and we got them to agree to ask for complete desegregation of the schools, immediately. He says, well I don’t think this is practical, because the people aren’t educated up to this, and we’ll have all kinds of problems. Well, I said, whether this is practical or not, this is what we want. Now what we will get, will perhaps be as close to this as the circumstances would seem to warrant, and this to me, seems to be the same kind of thing.

[00:28:47] Q: ________

A: Now you aim at the maximum, you aim at the moon, and try to get it, come as close to it as one possibly can.

[00:28:58] Q: To say back, in other words, if I still get what you mean, that the Freedom Now represents a concept of ideals and justice.

A: Right.

[00:29:12] Q: Which, to implement in the imperfect world, the implementation is subject to the pressures of the occasion.

A: Right, this is exactly right. This is what I mean. But now the Negroes for the most part, are not satisfied with less. This is something that’s been very difficult for whites to understand in communities where we have made some progress. I have had occasion to speak on progress in civil rights, or something, and my statement has always fallen on very unsympathetic ears, when I say that no amount of progress is satisfactory, because progress suggests process, it suggests a piecemeal kind of thing. And none of that is really satisfactory. What we want is not progress, we want complete freedom. Now, progress is something that fits into the picture, in order to get towards it, but we want everything right now. When we would go down and talk to business people, I would always start the conference, by saying, “We would like, to have your business desegregated by 9 o’clock tomorrow, since you’re closing within a few minutes today. In the morning when you open up, we’d like to have this business desegregated. And they say, “Well, of course, this is impractical, you know we can’t do this, and maybe some time in a distant future it will happen in the south.”

Well, then we try to come to some point between his distant future and my tomorrow morning.

[00:30:49] Q: Yes. Well, negotiating in those terms is one thing. The philosophical view would be quite different, relationships, wouldn’t it?

A: Yes, I would say so.

[00:31:01] Q: They’re not quite the same thing.

A: I would say they’re quite different, yes. But I’d, I don’t think that any ambition for any less than everything is adequate.

[00:31:16] Q: No ambition for that desire.

A: That’s right. Now, of course, ________ you will realize that all things cannot happen as you want them to.

[00:31:26] Q: As one young man said to me, in respect to this general topic, he said – I know about all the processes of social change, from my courses. But I hate to say it.

A: Yes, this is what I mean. ________. But you just don’t like it, this is just gradualism, this is less than the ultimate.

[00:31:53] Q: Words yet symbolically charged, don’t they, so they are not really used for this ________

A: That’s true, true.

[00:32:06] Q: Have you had much acquaintance firsthand with the matter of well, protection of ________ and advantages in the segregation pattern of Negroes, that they have a privileged position inside segregation, and therefore resist it in one way or another. The supreme case I know is an editorial I know written by the _______ this isn’t the title, but the Negro Business Association of St. Louis – integration would set the Negro business back 25 years.

A: Yes. Here, we have had a little, very little in fact, we’ve had people who had advantages because of segregation. There are all-Negro wards and this type of thing, and Negroes get elected as long as you have segregated housing, and you probably won’t if you don’t have it. We elect our councilmen by districts rather than by ward. Nobody is elected at large, except the councilmen at large. Others come from district. So if we didn’t have segregation, you wouldn’t have Negro councilmen. I understand that one hotel man, a Negro, was somewhat critical of our interest in desegregating the hotels. However we have very little of that.

[00:33:46] Q: I know that one of my friends in New Orleans, tells me that the Negro caterers in New Orleans, have protested, he did not, he is a caterer, have protested because, they desegregate facilities at the Hilton.

A: I see.

[00:34:10] Q: This has come to a real showdown between the caterers association and the Negro civil rights groups.

A: Of course, the Negro businessman ought to be able to compete with any other businessman. Integration has been seen much too much, Negroes wanting to get in something which white people own. ________ There’s much more to it. This is one of the efforts we have here; trying to lead the people into a real integration effort at our church here. Sure, I think that the other churches downtown ought to be open to all people, but I think we have an obligation here. We have to do something aggressive and overt, to make known the fact that persons of other ethnic identities would be welcome here.

[00:35:19] Q: It works both ways.

A: That’s right, it works both ways. I suspect our emphasis has been a little one-sided, in that regard. This may be part of the reason why some people are rather disenchanted about the progress that’s being made.

[00:35:38] Q: Is that true of the teachers at southern colleges, I mean, the southern Negro college?

A: I think so.

[00:35:44] Q: The segregated college, that’s the other possibility, what you just

A: I think for some, yes, but for those that are trying to measure up, this is very different. The difficult ideal thing is a college where young people will want to come, regardless of their race. Some will be weeded out.

[00:36:05] Q: Just not good enough.

A: Not good enough to stand the competition, that they will have to face.

[00:36:13] Q: It’s rather parallel to the old church colleges ________, church schools, isn’t it?

A: Yes, I suppose it is.

[00:36:20] Q: I mean, many colleges, with church schools, and withered away because they couldn’t meet the competition. Some, well all the church schools literally, except ________. Maintained their ________.

A: That’s quite true. The weaker ones will pass. There are calculated risks and we’ve

[00:36:20] Q: It’s very hard to know what will happen to some of the southern state-financed Negro schools.

A: Very hard. In West Virginia, the state Negro university became integrated and now there are more whites than Negroes there.

[00:37:06] Q: So I understand, they’ve had two or three departments that were better than anything around. Attract the white students in. At least partly.

A: So far, this has been the exception, rather than the rule.

[00:37:25] Q: Have you noticed any antisemitism among Negroes here? It’s very strong in some patches, you know, around the country.

A: I think you have more stereotypes here than genuine antisemitism. I think you have more actual stereotypes. You know, he’s a Jew and he’s thus and so, and thus and so. I don’t think it’s overt. Really. In any large measure at all.

[00:37:57] Q: There’s been no problem about it anyway.

A: No, no, we’ve had to meet with some Jewish merchants and so forth in connection with the same thing.

[00:38:09] Q: And they have been as cooperative

A: Yes. Yes.

[00:38:12] Q: Of course, we all know how this prejudice arose, in the Jewish ownership of housing, and the corner grocery and living in big cities. He’s the local credit guy. Local landlord.

A: Yes.

[00:38:30] Q: And have the stereotype around him. One more question, if I may, I won’t keep you forever. I’ve read and seen figures on it, and from very sources, the ratio of – tow things, one, Negro philanthropy to the Negro has been less than in relation to the resources, than that are due to Jews, or any other single ethnic group. Less giving to their own race, in terms of ratio resources. The second thing, in terms of supporting financially the civil rights movement, their ratio has been less than, say, the ratio of Jews, on anti-defamation, not a question of absolute figures, but a question of ratio of figures.

A: I would suppose that this is true.

[00:39:29] Q: Do you think that this is true here, or don’t you have any figures on that.

A: I don’t have any figures, I’ve heard many statements about it from people in various walks of life.

[00:39:39] Q: How would you account for this?

A: I don’t know, ________ I suppose I find myself becoming a kind of an apologist at times. It’s a rather easy thing to say – well, the circumstances to which Negroes have been subjected, would make them cautious and maybe not always even wise, not liberal, with their funds. There are no Negroes for whom money has been in the family for generations, you know, handed down, no Negroes like that.

[00:40:25] Q: There’s been no Negro Rothschild.

A: This is right, you see, no this generation just got it. The one who has it, you can be sure, struggled from the bottom up to get it, and this kind of thing. Well, this is part of what I would say I think I’m assuming the role of apologist. There is probably more to it than that.

[00:40:45] Q: Well, it isn’t an apology, that’s a question of fact, on the fact of records.

A: Oh, this is what has happened, yes. Whether or not this is the only reason, I don’t know. I think it’s related, I think it’s part

[00:40:59] Q: Some sociologist said, this is “the psychology of poverty,” yet ________ sociologist said, “Yet you have to conspicuous consumption.”

A: Yes, you do.

[00:41:13] Q: The self-indulgence, in our present time, which means not the psychology of poverty. That means two impulses in effect, that both can be said at just the same time. Do they have a common psychological ground, or common _________ ground?

A: I think so. That’s what I mean. ________ poverty and conspicuous consumption. Come out of the same soil, naturally, and they are in a sense, trying to do the same thing. It shows that there is no limit in what we have had and where we go and all, that we have tried to take what was accessible, and make it do for what wasn’t accessible. Like, riding a Cadillac, cannot substitute for first class citizenship, but sometimes you want to do something, which actually may not be wise, but you do it. And churches, the church may be the means of ________.

[00:42:36] Q: Yes, and just to get back to something else, I won’t torture you any further with this interview. One other question, how much of nonviolence is secular tactic, and how much do you feel in the range of your ________ is grounded on philosophical or theological basis?

A: I fear very little on the latter.

[00:43:06] Q: Tactic.

A: It’s a tactic, it’s a technique. It’s expedient tactic too. This is very unfortunate, I was talking with some British newsman, they weren’t really newsmen, ________ in this area yesterday. I was saying as I say now, that I feel a personal guilt for this, in this community, because I don’t think that we did the wisest thing in our movement here. In our workshops. We should have included a little more of the theological basis for our methods and goals.

[00:44:20] Q: The newsman, the British newsman, your guilt.

A: Actually I was saying yesterday to them, that now, that I feel, you know, that in our workshop sessions, we should have done more than we did. We should have kept the things that were happening within some kind of a theological frame of reference, which we did not do. I suggested it, but I was not insistent, and I was the leader, so I feel, I think some of the things that we did outside the church, should have been done from within the church. Of course, I’m using the church in the ordinary sense of the term. But we have not seen, not only nonviolence, but the struggle itself from a theological vantage point.

[00:45:12] Q: You know, well he said, of course, that the church has missed a big opportunity.

A: yes, I think he is exactly right. I think he is exactly right.

[00:45:20] Q: ________ missionaries in the Congo, ________

A: Yes. This is true. And of course, the church among the white people, (this is a very bad thing to do, describe the church in this manner) has not done it’s done its part. And the leaders in the movement, have for the most part, been ministers, or people connected with the church, the church buildings have been the places where you meet and this kind of thing. This church had to do a lot. The fire department required us to do a lot of things that cost this church, they usually said that the reasons had nothing to do with the struggle, but we recognized what was happening.

[00:46:01] Q: Putting pressure on you to fix it up.

A: Yes. Yes, we recognized this as pressure at the time. We spent money for this purpose. But even the involvement of Negroes, with ministers in the churches, this involvement has been non-theological, for the most part. This is the thing where I feel guilt, because I didn’t do my part in leading in this direction. I felt it, mentioned it a couple of times, but never pursued it.

[00:46:31] Q: Let me ask one more question, it’s really be defined. On the matter of a great number of Negro leaders who have come out of the south, or in the south still, there’s been a vast disproportion of the population in terms of education. The south has done much more than its share, of leaders in all levels, to the movement. It seems strange in the light of the, you might say, the more advanced situation, of northern Negroes in education ________.

A: This is the reason, I think. I’ve been wanting somewhere to speak to the subject of “the dangers of progress”. Because I think, for instance, people were more apathetic in Nashville, than they were in Montgomery, AL.

[00:47:26] Q: They were?

A: Yes. There were some things that we had in Nashville, we were not quite as segregated as they were in Montgomery, you see. And we weren’t really as aware of the problems here, as they were there. Here your eyes were opened. But the people here became involved once the problem was dramatized, they began to see what really happened. In the north, the concept of the problem, I think, is at fault. The concept of what the problem really is.

[00:48:04] Q: Could you say how you think that to be true?

A: Well, I spent a few months, in, well let me put it this way. This kind of illustration. During the heat of our battle, I was asked to go to many places in the north to speak, and the people wanted to sit there and sob and hear the horror stories of the south, the things that are happening there. I went to one community in Ohio, where there was a little lady sitting there, there were about three Negroes in this audience, and one of the colored ladies wanted to speak on a problem which she had in that community. The chairman did not want to hear about this, you see, because, “We came to hear Mr. Smith, and tell us about Nashville.” Of course, this is when I told them I would just end my part right there; let’s see what can be done the local problem. But there is a kind of hypocrisy, I think, the kind of false concept of the relationship between people of different races in the north, it is not as dramatic as it is in the south, you don’t have signs up, and so forth. Those people don’t really recognize what the problems are. It takes something like what happened in Cleveland the other day, to sort of dramatize in fact, that you have the same kind of problems.

[00:49:36] Q: Are you referring to Negroes as well as whites in the North?

A: I’m really referring to both. Now we went to Cleveland last year, spent a brief period there, and our children were in segregated schools for the first time.

[00:49:54] Q: Oh you had a church there, didn’t you?

A: Yes, that’s right, and returned here. But there in Cleveland, our children were in segregated schools for the first time. Never been in segregated schools in Nashville.

[00:50:11] Q: Because of their age, you mean?

A: Their ages. Their ages happen to be just right. You know, for the integration here. But there are many people who didn’t care too much for my saying that in the Cleveland community, in “enlightened” Cleveland.

[00:50:29] Q: This is de facto segregation.

A: Oh yes, yes, de facto segregation. Systematic and one of our real diseases in human relations.

[00:50:40] Q: Well, everything’s been fine, really fine, I appreciate it no end.

A: Well, it’s all right, I’m

[00:50:48] Q: And I’ll be sending you

THIS IS THE END OF TAPE 2, AND THE END OF THE CONVERSATION WITH REVEREND KELLY SMITH.

Collapse