TAPE 1 Searchable Text

Collapse

[These digitized texts are based upon 1964 typed transcripts of Robert Penn Warren’s original interviews. Errors in the original transcripts have not been corrected. To ensure accuracy, researchers should consult the audio recordings available on this site.]

Box23

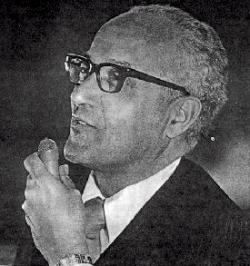

Avon Williams

Nashville

Feb. 14

AVON WILLIAMS Tape 1.

[00:00:43] Q: Let’s start with your vital statistics.

A: December 22, 1921.

[00:00:51] Q: Well, you’re a lot younger than I am. I was born in 1905.

A: Primary and secondary grades in Nashville, Tennessee, in segregated Negro schools there, college, Johnson C. Smith University, Charlotte, North Carolina, a segregated college, law school – Boston University, Boston, Mass.

[00:01:29] Q: Do you know why Boston University has had so many Negroes as students?

A: I do not know why of my own knowledge, because I never discussed it with any university official. However, I have gathered and I think my experience there verified that Boston University has been very liberal, when I say liberal, I mean, in the sense of disregarding ethnic difference in people in terms of their admissions and their teaching of people.

[00:02:10] Q: I know that a great many Negroes have been there, either in undergraduate or graduate.

A: Well, as a matter of fact, my enrollment in Boston University is an interesting story. When I was a senior in college, I wanted very much to go to Harvard, although I knew I might not have been admitted to Harvard anyway. But I did write to Harvard for an application, and they sent me a letter that Johnson C. Smith was not on their approved list. I was very young, and I went to see the dean of the college at Johnson C. Smith, and he suggested to me that instead of trying to do anything about getting Johnson C. Smith on the approved list, why didn’t I make application to Boston University, which was his alma mater. And so I did, and that, combined with the circumstances that tuition was less expensive at Boston University, caused me to finally end up there.

[00:03:27] Q: Did you settle in practice here immediately on ending Law School, or did you, were you somewhere else first?

A: I, my first experience in the practices of law was in Nashville, for on completing my legal education in 1948, I came, I was persuaded by my folks to return to Tennessee, and I had heard a great deal of Mr. Looby, so I wrote him, about coming down here, and as a matter of fact, came down for an interview, and as a result of that, I did spend six months with Mr. Looby in the year 1948-1949, on an interne basis, and then I returned to Knoxville in September of ’49, and initiated my practice there alone. And remained there until February of 1953, when I returned to Nashville, in association with Mr. Looby.

[00:04:34] Q: Were you in the war?

A: I was. I was drafted in 1943, February of 1943, the 9thof February, as a matter of fact, and was separated in August 1946, approximately 2-1/2 years overseas.

[00:04:56] Q: Did the war experience, as it did in so many other people, have some effect on you, in your attitude toward civil rights situation? Was it fixed before hand, or did it become fixed afterward in developing part of your convictions and career?

A: I would say that anyone born in the south, and reared in the south, would have, any Negro, with any powers, of perception at all, would have to, would have to have some rather fixed attitudes, long before the age that I went into the army, which was 21 years of age. I would say, however, that some of my attitudes were intensified by reason of the experience in the army, in a segregated army, and in the, in some instances in places where the discrimination was just rather open and vicious, in addition to being discrimination in terms of segregated organization, units and that sort of thing. Such things as px’s and certain other types of discrimination, and that sort of thing. Yes, I would say service in the armed forces, did intensify some of the attitudes that I had already developed as a result of my experience as a southerner.

[00:06:47] Q: Let’s go for the moment to the matter of the Nashville sit-in and the boycott. How did the sit-ins arise, just how much, how much was organized and how much was spontaneous?

A: I frankly do not know how sit-ins arose. I had read very little of the movement, prior to the time that it happened, I knew nothing whatsoever of the organization of the movement, prior to the time that it happened. I had of course, read in passing, of the Greensboro incidents a few days before they began in Nashville. However, I had no idea that it was going to occur in Nashville, and I was as surprised as anyone else, when the news came out on, I believe it was either the 17thor the 27th, I forget which, of February 1960, when they had the mass arrests here. I believe it was the 27thand we were called into it to represent them.

[00:08:12] Q: You’d been active of course, for a long time, in civil rights?

A: Yes, in N.A.A.C.P. activities, local and national, right. Your initial remarks were interesting to me, because as a matter of fact, when I finished, I – all the way through Law School and when I finished Law School, I said that I was not interested in civil rights, as an area of legal endeavor, and of course, I have a cousin, who was an active lawyer in the area of civil rights, with the N.A.A.C.P. – an older established lawyer, and when I, as I say, my folks persuaded me to come back to Tennessee, I said -- “well I don’t know what I can find to do here”, my father said – “why don’t you be an N.A.A.C.P. lawyer”, and I said -- “I don’t want to be an N.A.A.C.P. lawyer, I just want to be a lawyer”. In fact, I didn’t want to be a Negro lawyer, I want to practice law. But one could hardly, even interne with Mr. Looby, without developing some sense of obligation in this area, and I think that that probably began at that time, and then when I returned to Knoxville, Mr. Carl Cowan, who had been a stellar figure in that area, as a lawyer representing people in that area, was Chairman of the Legal Redress Committee of the N.A.A.C.P. there, and he asked me to serve as a member, and of course, I couldn’t turn that down, and then we very soon got involved in the University of Tennessee case, and then just kept on going.

[00:10:20] Q: So that one encounters very often, the question of ambitions and aspirations have no relation to civil rights, and somehow, you’re suddenly in it.

A: Yes, after that, well, I told, it’s sort of like Mr. White, a lawyer who has an office here on the same floor, says. He’s a graduate of Howard Law School, and he says that when he was there -- Howard of course, is the place where Thurgood Marshall was educated, and people whom we think of as being the great and familiar -- The Negro leader greats like Charlie Houston, and Andy Ransom and Jim Nabritt and others, either taught or attended the school, and White was there during that time, and he says that he doesn’t see how anyone, could attend school at Howard without being infused with a sense of obligation in the field of civil rights, obligation and duty to participate in this aspect of legal activity. And so I suppose that in a sense you could broaden this out and say that any Negro who has lived, who has lived in the United States, and seen what goes on, must have a very poor sense of obligation or duty, if he doesn’t sooner or later, whatever he may do, come up against some situation that involves him actively in this field, and which he can’t turn down.

[00:12:17] Q: Well, Robert Moses told me he was registered in Harvard in Philosophy, for a year, ________Ph.D., and he walked away from that, when he was in Mississippi, changed direction, almost immediately, ________ philosopher.

A: I didn’t know that.

[00:12:43] Q: I had a long chat with him, three hour talk with him.

A: I suppose you talked with Martin Luther King,

[00:12:50] Q: Not yet, I’ve talked with Abernathy, ________ going back again.

A: Well, I do not know Dr. King personally, but from what I have read him, he falls in that same category.

[00:13:06] Q: Let me ask you a question that I’ve run into. I ran into this long ago with DuBois. He says -- this is a dilemma for many Negroes, a real split in the psyche, for many if not for all, on the one hand, the pull toward Africa, the mystique, the sense of community of the Negro in America, the sense of a Negro conscience, a Negro tradition, a Negro involvement. He outline the ________ , and black mystique, ________ emerging in the African picture. And appeared in what we see in form in the Black Muslim. And on the other hand, the impulse to identify with the western culture tradition, western European culture tradition, the American aspect of it too, and to move towards that, to embrace that, to be integrated with that, and to perhaps eventually absorb in that stream ________ into the bloodstream of western European world, with the loss of identity, absorption and loss of identity. To some Negroes it is a real problem, as it is for some Jews, a question of maintaining the Jewish, not necessarily religion, but cultural identity, in the place of the pull toward the ________ Christian tradition or ________ tradition. Does this present itself to you as an issue or not?

A: Well, yes, I suppose as, although I don’t know whether I would consider it very much of an issue. I think, I just don’t know, I believe that people are taught, after they are born, -- I don’t think, -- I believe that here in the United States, here in the south, let’s say, I believe that white people are taught by their own people, and by themselves to be proud, they are taught to love white people, and to think that white people are beautiful and wonderful and intelligent, and, in fact, that they embody all the desirable attributes of life. Negroes, on the other hand, from the time they are born, are taught not only by the white people, but by their own people, that there is something dirty about them, that there is something substandard about them --

[00:16:18] Q: By themselves.

A: By themselves. And they consequently have what we call an out-group preference. Even many Negroes who have been characterized as among the most militant, sometimes catch themselves doing things and saying things that are part of this early training, which can be described by the phrase “white is right”, what the white man says and what he does, is the correct thing. And of course, I think Dr. DuBois is right in this sense, that the ego, that the ego, of the individual certainly rebels against this sort of training, and this sort of indoctrination, it rebels at some point along the line, although sometimes a man is an old man, before he all of a sudden realizes that this is after all, a whole lot of junk, and many people maybe go to their grave, never realizing it. Maybe this is one of our problems in the south. But as I see it, this is not so much a problem, or an issue, of psyche, as it is an issue or a problem of training and -- just straight training and indoctrination. And I’m just afraid, of course, the Black Muslims, represent an application of this same type of training in reverse. In other words, doing the same thing, except doing it the other way. And it may be that the world needs something like that, it may be that the only way that the white people can be taught to see that they are not after all, the essence of perfection is to be exposed to a world in which the majority of people in power look some other way and act some other way, and talk some other way, and discriminate against them in the same way that they’ve discriminated against Negroes, and have the power to teach them in the same way that they’ve attempted to teach colored people, to hate themselves. It may be that they require it, but I don’t think that they require it. I do think that Negroes to some extent – no Negroes, have been exposed to this, and maybe in the present situation, it happens even with regard to white people, the Negroes do need to be, need to come to the realization that after all, black is beautiful – that black people are beautiful. For instance, we ourselves say “the picture looks black”. We say it looks black, and we picture it as unpleasant. And for instance, right now, I am having to undergo a conscious course of self-indoctrination, to eliminate these expressions from my vocabulary. I’m having to teach myself to remember that black, after all, is a warm color. That the connection of white with knowledge, and black with sin, is a man made connection, not a God made connection. And we could have it just the other way around. For that matter. So I, with regard to Africa, of course, that’s _______, but I think I got what you were driving at, what you were saying, what you were suggesting, that Doctor _______, I wasn’t familiar with that particular book of Dr. DuBois. But I think that what you were saying, was that he was saying that the Negro psychologically is pulled two ways.

[00:20:53] Q: That’s right.

A: Well, I think actually the Negro is actually, pulled one way – he’s pulled toward the white culture, of which he’s a part, and there’s absolutely nothing, there’s nothing wrong with the Negro submitting himself to a pull towards the culture of which he’s a part. But when that culture teaches him that he is inferior, and teaches a majority group, which is only one of its many components parts, that they are superior, well this does create a problem for him.

[00:21:36] Q: Very astute formulation, I think, very different formulation from the other one, isn’t it? There’s a lawyer that I talked to in New Orleans ten days ago, a man of highest quality intellectually and personally and he’s very active in civil rights. In fact, I was back, in New Orleans, Louisiana. He said to me, on this general point,

A: Was that Mr. ________?

[00:22:11] Q: No. He said to me, I hate to say it, but it’s been my experience, that I don’t see how the white man can be changed. He said -- I am leaning to the Black Muslim position. This is a man who is not the ordinary person at all, this man has a successful law practice, and he said – it’s against all my philosophy. He said -- I’m beginning to feel this emotional drag toward it and conviction that they are right. The white man is unredeemable.

A: Well, of course, I could not agree with this, -- if you intend by that to ask me what my thinking would be, with regard to that.

[00:23:05] Q:: Well, ________ this is a man, who says this is against all my philosophy, and all my beliefs, it’s beginning to take hold of me.

A: Well, I wonder if that man, I wonder if he has read anything about what the Black Muslims propose. I don’t think that I have read anything, not even a great deal of it, but I do understand that one of their, one of their ideas is, that segregation is a natural and desirable and a good thing, a proposition with which I am in complete lack of agreement. They likewise seem to propose that you can fight violence with violence, a proposition which does not appeal logically to my mind; but I think more basically, it seems to me that we can hardly argue against arbitrary prejudice, and discrimination, if we are guilty of this ourselves. And of course, the philosophy, as I understand espoused by the Black Muslims, does involve simply meeting the problem of the white man’s arbitrary prejudice, by being arbitrarily prejudiced against him.

[00:23:05] Q: The white devil.

A: Yes, which, of course, is like saying, you see a mad dog coming down the street, the way to solve that problem, is to start foaming at the mouth yourself, and run down the street and bite him first.

[00:25:05] Q: That’s pretty good. May I read you a quotation from Dr. Kenneth Clark, the psychologist at C.C.N.Y., on Dr. King and nonviolence? “On the surface Dr. King’s philosophy to have health and stability, while that of the Black Nationalists, betrays pathology and instability. But a deeper might reveal that there is also an unrealistic if not pathological basis in King’s doctrine. The natural reaction to injustice brings bitterness and resentment. The form which such bitterness takes, need not be overtly violent, but the corrosion which is involved is inevitable. It would seem therefore that any demand that the victim of oppression be required to love those who oppress them, places an additional and probably intolerable psychological burden upon the victims.” How would you respond to that?

A: I would agree with that only if I were not a believing Christian.

[00:26:28] Q: Only if you were not a believing Christian?

A: If I were not a believing Christian, that is, if I did not believe, in the, for want of a better word, I can say, the improving nature of self-sacrifice, then I would say that what Dr. Clark says, is logically true. I of course, agree with this – I would agree with something that he implied in there, but he didn’t get around to, and that is, that Dr. King’s philosophy is not a single solution to the problem of human relations in the United States or in the world.

I think for instance, Dr. King had a great deal of difficulty solving the problem which all of us have, with regard to the -- that part of the doctrine, which says -- we observe only God’s law, we are entitled to break man made laws, if our conscience says that they are wrong. Of course, he wasn’t the originator of this and he’s not the last man who will ever say it either. And yet, we strive to change man’s law, and once they are changed, to exact obedience to the laws, and if someone attempted to break them, we wouldn’t talk about God’s law first, we would talk about breaking the man made law first. This problem of the, I don’t know whether he uses the word dichotomy or not, but anyway, this problem of conflict between God’s law and man’s law, and how man can reconcile the adherence to man’s law with the conscience, and at what point one can break man’s law. I think this is the most interesting thing about Dr. King’s philosophy. But insofar as it’s being erosive or corrosive or anything, or pathological, if you tell me to love a man who hates me, I think it’s so far from being that, that on the contrary this sort of ________ improves a man, that it makes him a stronger man, emotionally and intellectually.

[00:29:24] Q: James Baldwin writes about the southern mob and the southern majority will, as follows: “The most trenchant observers of ________ south, those who are embattled there, feel that the southern mob are not an expression of the southern majority will.” Their impression is that these mobs fill, so to speak, a moral vacuum, and that the people who spawned them, would be happy to be released from them.

A: I don’t agree with that. When I got the word that President Kennedy was dead, I happened to be in a group composed primarily of white men. These were several men there, and I caught – when this word first came, someone came to the room, and came directly to me, I don’t know why he came directly to me, and said, “Avon, the President has been seriously hurt, in Texas, he’s been shot in the brain”. And I saw a white man with an unholy grin on his face. And then the person went on to say “And Governor Connolly and Vice President Johnson were also shot, critically injured”. And all of a sudden, the grin wiped off his face. This type of -- I think that really epitomizes my answer to that question. This man was a respectable man. He was a high ranking officer, in the United States Government. I think, I would like to go back, I really didn’t, in answering this, I would like to, I really didn’t say what I should have said about this matter of loving those who hate you. I think that many of us misconceive what loving those who can hate you, means. Loving -- love does not mean what the white man has traditionally thought it meant. It does not mean being blind to faults. It does not mean being afraid to tell him when he is wrong, or when he’s being stupid. It does not mean being afraid to fight him, in a legitimate way. The love that I’m talking about, is the type of love which is a very intelligent Christian has for a child. After all, as I see it, although the white man has accused the Negro of being a child in the American society, I think that if you look at it realistically, you will find that the white American, has displayed the more childish tendencies. That it is he who has failed to accept the responsibilities of a mature man. Take, for instance, his violation of the Negro slave woman -- a completely unrestrained and childish impulse that ignored the mature recognition of the facts of life, or any insights into the future. The Negro woman, on the other hand, I think, although she was unable to help herself, I think history teaches that she has come off far better, in terms of demonstrating a maturity, a recognition of the responsibilities of life, to herself and to her children. The fact that we have so many Negro men now who have gone so far in life, is a result of some Negro mother washing and ironing and working hard to get that child into school, and to gain an advantage for him. So I say that love, involves chastisement, and I think that the White American needs a whole lot of chastisement. It involves other forms of correction. It involves making an individual receptive, whether he wants to or not, it involves a whole lot of things that we don’t think about when we talk about love. And I think Rev. King’s philosophy has something to do with this. I think the fact that they don’t draw back at all. But, with regard to faith -- and I think that to say that this very last thing, this quotation from Baldwin, is this type of unrealistic thinking that wants to love the white man because he’s pretty, according to what he has taught us; he’s intelligent and he’s good, according to what he’s taught us -- so we just overlook all the mean, evil traits. For instance, a little elderly lady who here in Nashville, is a secretary over at the courthouse, 60 or 70 years old -- just as sweet as she could be -- but every time she would get me by myself, she would start telling me about how race relations were bad nowadays, and she “wishes we could go back to the old days”, and “Negroes don’t want this”. Now this is mean, you see. This was not a real desire to help us, but rather a plan for us to try to relieve white people of the responsibility for the mobs which they permit to exist, you see, or the mistreatment, you see, which they permit to exist, or the evil in their own lives, which they permit to exist. If we’re going to relieve them of it, then this shows that we haven’t even recognized the responsibility of driving similar ideas and similar evils out of our own lives. So I first say, I would say that the quotations from Baldwin is incorrect, but I would say that the solution to the problem, is not condemnation, I would say the solution to the problem, is to attempt to make the white society which does not actively participate in the mobs -- I think the ones who are in the mobs, want to be there -- but to attempt to make the majority of the white society which does not participate in the mob, recognize its responsibility, for after all, that same white society has -- since I was not even able to understand -- has driven me to recognize my responsibility for the shiftless Negro, for the Negro drunk, for the Negro community. As a matter of fact, it will not even allow me to escape, or it would not until I got accustomed to it, and now I don’t want to escape. I wouldn’t want to live in a white neighborhood now, because I’m accustomed to, I’m so accustomed to the things that go on in my neighborhood that, I wouldn’t feel so comfortable without it. But I don’t want my son to be deprived of the freedom of selection of the community within which he lives. And interestingly enough, I heard a white man, say it, a very intelligent white man, a member of the faculty in one of our great southern universities. He said, from the witness stand -- this was Dr. Camp down at Sewanee, one of the plaintiffs in our school case there, one of the county attorneys, the attorney for the school board, made the mistake of asking him during the hearing, why he wanted his child to attend a desegregated school system. And he gave them a very short succinct answer. He indicated that he was born in Virginia, and was deprived of his freedom to choose as a child, and he wanted his child not to be subjected to those same restrictions on his mind, and on his freedom of thought. Said he wanted his child to be able to choose freely, and I think he meant by this, freely in regard to all of the facts and aspects and phases of life. Freedom to choose his friends and everything else.

[00:38:25] Q: We hear a lot about the stereotype of the Negro by the white man. Sometimes a contradictory picture, might be shiftless and dangerous, and this and that, but they are all part of stereotype, even though they are self-contradictory in the stereotype.

A: And, wait a minute, if he has any admirable traits, this is nearly always unaccepted.

[00:38:57] Q: Well, what about the Negro’s stereotype of the white man? What are the qualities of that stereotype?

A: The Negro’s stereotype of the white man, is encased in the same ignorance as the white man’s stereotype of the Negro. I would say that the major difference is that the Negro stereotype of the white man, has been more or less an ignorance that he could not do anything about, because he was shut entirely out of the white man’s environment. Now the stereotype of the Negro was not something that the white man couldn’t do anything about, because he had complete freedom within the Negro environment and community. The stereotype of the Negro was a deliberate stereotype in the sense that it accomplished a mean and evil desire, in my opinion, to accomplish the end of eliminating the Negro from that environment in which the white man lived, except in terms of being unobserved. You know the thing, what I mean by that, there, but unobservable. So I would say that the ________, and also, the Negro stereotype of the white man, has been a euphemistic one, for instance, I’ve heard Negroes say -- “well, he’s perfect, just like a white man”, or “he acts like, he talks like a white person”, or “he acts like a white person”. And this is all a part of that old brainwashing, or training, if you prefer -- but I don ‘t think training is the adequate word -- because it’s emblazoned from virtually every billboard that we see, and has been for ages end on end, or magazines, toilet doors, television, radio, (of course, television has been improving recently) newspapers, every thing, stereotyping the white man as being a perfect individual.

[00:41:42] Q: Is there another stereotype opposite to that among the Negroes, for the white man the ________, cruel, the avaricious, unimaginative,

A: I think yes. This is -- no, I don’t say this, I don’t think this is a stereotype, because I think that the Negro, and really this is one of those problems, I don’t like the word stereotype. I think the only thing that you can call a stereotype is this idea that has been brainwashed into the Negro that white is right. Now this is just, this is what the American Negro thinks of, subconsciously, before he has the chance to even think about it. I think in terms, when you say stereotype, you refer to some concept that isn’t necessarily true……

[00:42:41] Q: No.

A: …..that is imposed on a group, imposed on a group, as being applicable to all members of their group, without any individuality. And I don’t think that you can get that, anywhere you go, with regard to the American Negro’s concept of the white man, because it is contrary to his thinking. He has always dealt with the white man as individual. He has thought in terms of the white “man” as an individual. He, when he talks about white “people”, it is in terms of the “system”, not in terms of the -- of the particular characteristics of some particular man. For instance, a Negro will say -- “that’s a mean white man”. “That’s a good white man.” “he’s just a mediocre white man.” In other words, what I am saying is -- and maybe white people wouldn’t like to hear this, because I think this is really a mark of intelligence -- the Negro has been able to discriminate on an individual basis.

[00:43:58] Q: He had to, didn’t he?

A: I guess he had to. Yes he had to -- to a far greater extent, and very little stereotype, and as a matter of fact, the Negro has to keep telling himself not to trust this white man, or that white man, because, he has to tell himself -- he has to be taught really -- that no matter how intelligent or how pleasant, or how kind, or how Christian, any particular white man is, if there ever comes an issue, a basic issue, that relates to the identity of one white man to another, - and I believe this – the white man will always stick to the white man.

[00:44:48] Q: Well, now, how about the Beckwith jury trial? You are talking like my friend, the lawyer in New Orleans.

A: No I’m not, no, I’m not. I’m not saying ….. I’m not saying that, I’m not saying that in the sense of condemnation, I’m saying that this is the cost of the childish selfishness which is taught to the white child to continue as, until he’s 70, and then…..

[00:45:23] Q: He’s taught that, yes, sure he is.

A: And so I’m saying that it’s right difficult for him to get away from it.

[00:45:32] Q: It may be difficult, but the question is whether any succeed, you see.

A: Oh, well, I guess maybe I shouldn’t have said that to you, because I don’t believe there’s anything that somebody can’t believe in. And I believe, of course….. of course, as a matter of fact, there are white people who in my opinion, make far greater sacrifices for Negroes than many Negroes are willing to make for themselves.

[00:46:04] Q: I ran into a strange thing, very natural to you, I guess. In Mississippi, in my talks with people, quite a few Negroes, of different levels of intelligence and training, said the same thing. ________, the whites who have come into the civil rights movements in Mississippi and Alabama, have sometimes had it very rough, despite any sacrifices they were making, now this has been for different reasons, and I’ve had Mr. Robert Moses about this at length, ________ some of the Northern Negroes who’ve come in, had it rough. But by and large, there’s been friction on this part, the white man coming into this, say S.N.C.C. or N.A.A.C.P., actually.

A: Yes, I think this is definitely true.

[00:47:08] Q: They’ve had real problems.

A: My real quarrel, I didn’t really get to the heart of the thing, when I was discussing the same thing.

[00:47:19] Q: Yes, but these do.

A: I think the real heart of it, the thing I was trying to hint, when I said, you can hardly find a white man who when it comes down to something basic – when it comes down to his identity as a white man – that he won’t be with the white man. I said that badly. What I should have said, was, he would not rid himself of his white skin, of his identity, as a white person. I think this is related to what you’re talking about, because it’s the same problem, that the white man, the white person, who is in Mississippi, in Texas, is more heckled than a Negro, if he espouses his cause. A white friend of mine likes to brag about the fact that he got beaten down in Montgomery, and I tell him, as a matter of fact, you have no right to brag to me, or to complain to me, because your head got beaten in the interest of the Negro, because your head didn’t get beaten in the interest of the Negro, it got beaten in the interest of humanity. And when you say it got beaten in the interest of the Negro, and you say thereby you’ve done something for me as a Negro, you’re depriving me of my individuality. So far as you know, my grandmother may have been white and my grandfather may have been white. If that be true, then I have a right to complain – to say to a Negro in brown skin, with more brown skin that I have: “you ought to be prouder of me than you are of yourself, when I put up with some privation in the interest of humanity, because I’m whiter than you are”. You see, what I’m trying to say is you’re still going back to your pride and identity as a white person, you’re still setting yourself off as God’s chosen child, and I don’t see anywhere in the Bible, where it said a white skin made people God’s chosen children.

[00:49:18] Q: One point of friction, that was described to be by several people, is the ________ that white people who try to “go Negro”, come into the movement, take up a special Negro, what they conceive as a Negro quality, ________ certain language, certain ways of speech, certain attitudes they assume to be Negro, then they absorb these.

A: There again, I think the problem is, the problem is, that whoever is resenting that, is not recognizing that individual’s right, what do you call it, you don’t have to be a Christian to, I started to say – God given right, but I think if you just have any capacity for, to handle an idea, or to think, you ought to recognize that by virtue of his being an individual, that an individual has a right to like things, individually. Now you can’t, just because I like something that somebody has stereotyped in a Negro way of doing things, - or you can’t tell me: “you don’t have the right”, to cast an aspersion on that, or say that I am, or to classify me even as, a Negro, because I do it. This is contrary, I think, to basic individual human dignity. Of course, the thing that really makes this type of thinking ridiculous, is that what happens nine times out of ten, is that somebody smart comes along, and gets some white person, who is above reproach, involved in some cheap imitation of the same thing, and it gets all erased, and they start calling, they give it, like rock ‘n roll, for instance: jazz and blues, and all initially was called Negro music, that’s all it is. The Beetles -- girls raising cain about them last Sunday night. Now why doesn’t somebody say, “this is Negro music, you white girls and boys, you forget about this, this will corrupt you”. This is, of course, this is ……. This shows the ridiculousness of the whole thing.

[00:51:52] Q: That’s one of the points ________ based on the uses made of Negro music.

A: Why should I dislike opera? Why should I dislike grand opera? Just because, so far as I’m aware, no ________ Negro has ever composed any grand opera that is considered a masterpiece. If I happen to like grand opera, that’s my business, and no one should have the right to tell me I can’t like it. If you don’t recognize this, if any American fails to recognize this, taking it to its fullest extent, then he needn’t talk about dictatorship in communist Russia, or communist anything else, thought control, or anything else, because this is what he is participating in if you don’t recognize an individual’s right within the area of human society, to think the way he wants to think, to associate with whomever he would like to associate, to be freely educated in that society, freely choosing and rejecting his companions within that society, and not on the basis of any stereotype which society imposes either by virtue of the state or by virtue of what is tantamount to the state: group stereotypes and customs which achieve the status of law by virtue of various human factors.

[00:53:40] Q: In the light of what we knew of the social process, and evolutionary process, what is the content of the phrase “freedom now”?

A: In the light of what?

[00:53:52] Q: In relation to the social process and the revolutionary process -- it always a movement in time, what is the content of the phrase “freedom now”?

A: I think it’s a battle cry. It’s a battle cry. It means that nobody, no Negro who has any sense, knowing the way the so-called public officials have operated since 1954, knowing the way the so-called Christian white people in our society -- I’m not condemning them, I’m just talking about looking at the fact -- knowing the way we have seen them operate since 1954, no Negro who has any sense, is going to be unrealistic enough to expect that without a fight, any appreciable segment of white society, is going to give him anything. It means that many of us for a long time have realized we’re in a fight, more and more of us will realize we’re in a fight, and we’ve got a battle cry, and it’s that we will no be put off, by promises, that never come true.

[00:55:35] Q: How do you think the negotiations went here after the boycott?

A: Kind of badly at first, I was not a part of the negotiations, we just handled the lawsuits. But, so maybe I shouldn’t try to express an opinion on it.

[00:56:09] Q: Either on the record or off the record, it doesn’t matter to me, I’m just curious to know what you ________

A: I would say that …….., off the record, I would say that the negotiations in Nashville started off in a modest way, during the course of those negotiations, the attitudes of and thinking of some very powerful white people, were modified, not changed, modified. And that modification permitted subsequent negotiations which have been more fruitful, but not half as fruitful as they ought to have been.

[00:56:59] Q: In other words, a lot remains to be done.

A: A whole lot remains to be done in Nashville.

[00:57:04] Q: But was a precedent set for the process?

A: Yes. Apparently the precedent of involvement of important, community and financial figures in the negotiating process.

[00:57:24] Q: It’s reached the point where the responsible people have to be involved, they can’t stay out, that’s the big gain?

A: Well, it all depends on what you mean by, “have to be in” and “can’t stay out”. These people, I think come in, simply because they feel, they’ve begun to feel for the first time, that they have a financial interest in preserving peace.

[00:57:46] Q: The pressure is on them to preserve peace.

A: Yes, it’s a financial pressure more than anything else. I think if it were a question of merely preserving public peace, I think you’d see a whole lot of Negro children still sitting out there in jail, since 1960.

[00:58:04] Q: It’s self-interest.

A: Right! If the Negro hadn’t used the weapon of the economic boycott, and if that weapon were not always there, these biracial committees that are getting all the headlines, and all the credit for our progress along with the Mayor, would probably never have existed in the composition they presently assume and we would never have made one fourth as much progress.

[00:58:04] Q: They don’t really play from strength in other words?

A: That’s correct, that’s correct. Sort of like the same proposition that we have in dealing with the Russians in the cold war; it’s all very well, and I believe in negotiating and bargaining to preserve the peace, but at the same time, you don’t have anything to bargain with, unless you have some strength, and when you have strength, you don’t sit around and bargain away your basic rights and basic principles.

[00:59:06] Q: I know you have a home, I should like very much to

END OF TAPE RECORDING

(one tape only) - (handwritten note)

Collapse