Barber discusses issues of black identity and the effect of growing African American populations in urban centers in the North and the South. Barber hypothesizes as to the then-current status of the civil rights movement and white Americans' acceptance of African Americans, and he also considers sectional differences in the pace and progress of the movement. Additionally, Barber comments on civil rights activities in Memphis and he discusses civil rights legislation.

Carroll Barber

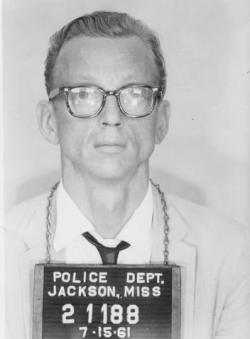

Carroll Barber (1924-1999) was born in Geneva, Illinois, and completed his undergraduate degree at the University of Michigan in 1948. Barber later received a graduate degree in anthropology from the University of Arizona. Barber participated in a Freedom Ride from New Orleans, Louisiana, to Jackson, Mississippi. He was arrested on July 15, 1961, for his participation. Barber later served as a part-time instructor at Fisk University in the anthropology department.

Transcript

TAPE 1 Searchable Text

Collapse[These digitzed texts are based upon typed transcripts created in 1964. Errors in the original transcripts have not been corrected. To ensure accuracy, researchers should consult the audio recordings available on this site. Time stamps are included in the retyped transcripts to aid in this process.]

[Note: "Barker” is an incorrect trancription that appears in the original document. This interviewee’s last name is Barber.]

Transcript of Taped Conversation

MR. ROBERT PENN WARREN and MR. CARROLL BARKER

at Fisk University – February 15, 1964

[00:00:28] MR. WARREN: I would like to know, to start with, what you know of the genesis of the sit-ins in Nashville.

MR. BARKER: That I couldn’t tell you . . . . .

[00:00:37] MR. WARREN: You came in after --

MR. BARKER: I came here in December ’61, and the movement . . . . .

[00:00:42] MR. WARREN: After that you said two years ago, and you weren’t here at the time of negotiations, either, the wind-up. Well, this fact -- I didn’t know until you told me, a little while ago, the things that . . . . . . you don’t have to. . . . . . the things that . . . . . this is a-- we’ve got a lot here to talk about. The whole notion of this psychic split in the, in the Negroes, if there was anything, the pull toward . . . . . in the mystic world, the black man’s culture that we dream about, any of those things, opposed to the impulse to enter the mainstream of Western culture and in the end, perhaps lose identity, and I get all sorts of different replies to that notion, you see.

MR. BARBER: I imagine you would.

[00:01:50] MR. WARREN: All sorts of different replies.

MR. BARBER: My own ideas change on it all the time.

[00:01:54] MR. WARREN: They do?

MR. BARKER: Frankly, I feel that in the next few years we’re going to see an increase in black chauvinism or whatever you want to call it. I don’t think it can withstand the pull of the predominant culture and all . . . . . foresee . . . . . an anthropologist. Theoretically, I don’t see it, and from the standpoint of people I know who are not, say, involved, so thoroughly in the movement and who are not -- if pront [prone] to, go all out on this. It just seems to me that it would be a very unlikely development. You would get a long-term-- a long-term expression of this, in ten, twenty years, but I would be doubtful if that.

[00:03:10] MR. WARREN: Well, apparently this a problem for a good many Negroes who talk about it in that way, some sense of a real split in feeling, some really. . . . . . problem.

MR. BARKER: I’m sure it is. I mean I could see a -- I have a feeling in a sense that an expression if it really hasn’t been possible or permitted until relatively recently, and it’s a very human reaction, I think, to the situation. I forget who it was that said, well, what people talked about colored so long that the Negroes finally decided it was important. But this is the sort of thing that we’re getting now, but when you think of the -- figure I always like to use is what is the world going to be like in the year 2000? And I just can’t see that a –- I can certainly see an amount of pride in one’s background, and so forth. I really can’t see Negroes developing into a minority on the order of the Jews, or anything of that kind.

[00:04:29] MR. WARREN: You don’t see the --

MR. BARKER: No.

[00:04:31] MR. WARREN: There are certain Jews I know, and even a couple of psychiatrists, who draw a parallel between the split that some Jews feel, even Jews who have no religion, and the Negro situation in this moment; but one other thing related to this, and I don’t know how much of a question this really is, you read and people say that the cutting edge of the present civil rights and the new Negro and all of this pattern of things is -- depend upon the fact that the Negro has changed his view of himself and accepted his identity and identification with the Negro race or the Negro group or the Negro culture or any of these things, whichever way you want to say it. This discovery of self has given a cutting edge, psychologically. If that’s true, then it is not merely a detail, you see, then black chauvinism is not merely a detail, if you want to equate that with black chauvinism, which I don’t think necessary in either problem. But how would that, what kind of lead would that give you to . . . . . on?

MR. BARKER: Well, I think you can make a distinction between --

[00:06:10] MR. WARREN: You say you can’t.

MR. BARKER: You can make a distinction between what I call black chauvinism or what is the most virulent expression, the Muslim movement, and a simple feeling of worth, a feeling of pride. As I say, this-- I think there’s a difference, and what I was referring to in particular was the expression on the order of the Muslim movement, I cannot see being a permanent feature. This other will last in varying degrees. There will be families that will be horrified when prospective white brides or husbands are brought home, and which there will be on the other side of the line. And I certainly don’t see a real quick physical amalgamation, no. But I don’t think the barriers are nearly as strong and in areas, small areas, sort of marginal areas to the general society where these things have lost their potency, the obstacle disappears. So that I think it will be an eventual prospect. I don’t think it’s a very important one from the standpoint of Negroes, and I think a great many Negroes are beginning to look at this with a certain amount of fear that this may be, and --

[00:07:53] MR. WARREN: The fear of the loss of identity?

MR. BARKER: The fear of the loss of-- yes. I wouldn’t predict 100 per cent, because there are too many factors in the world that are going to influence it, and we don’t even know about, we haven’t identified, but this is too far in the future. I’m thinking partly in these terms because yesterday we had a group of students from Colombia, South America here, and they were looking for these solutions to the problem. . . . . . And I said: What do you mean by solution? And finally I said to them, I said that at one time Colombia had approximately the same percentage of Negroes and white people in the United States today, and I said: You seem to have rather successfully integrated. And in appearance it was obvious too.

[00:08:52] MR. WARREN: How much do you think is in Leslie . . . . . . notion, is secret motivation, if that’s the right word, in the Muslim redemption of the outcast and all of that with . . . . . . and CORE, as a way of channeling ambitions, aspirations, to join the middle-class white world, accept its values, it’s a strange backdoor way of getting into the middle class rather than in a withdrawing from the American white middle class white society.

MR. BARKER: I must confess that I have not read his book. I’ve read Lincoln’s books.

[00:09:44] MR. WARREN: That’s about it. He was saying that with apparently exclusiveness and chauvinism . . . . . seize the impulse in training schools, and always to come back into the established . . . . . values.

MR. BARKER: It sounds very reasonable to me, and this is the reason I said what I did at the beginning. The pull of western civilization even on people who thoroughly dislike the groups who thoroughly suffer from it, is so tremendous today that I can’t see it being withstood, and this is-- I’m going to have to read the book, now that I’m interested in this. I hadn’t heard that something like this was in it. In a sense, you can look at the Muslims and say well, this is substitute for this acceptance, but after all, the Black Muslims are American; they grew up in America, their cultural background is American, and they can study the Koran and learn Arabic all they want to. They’re still Americans, and so I wouldn’t be surprised at all sorts of covert acceptance of ideals, but at the same time that these are being rejected overtly.

[00:11:20] MR. WARREN: That’s one of his ideas in the book, and you can go over that at some length.

MR. BARKER: You’re really digging in the area where you can’t prove anything, I’ll say that much.

[00:11:39] MR. WARREN: You can’t prove anything.

MR. BARKER: And as I’ve mentioned, that we don’t really have all the facts, and we don’t know how to deal with them. Certainly the fact that Negroes are pulled every-which way today is true.

[00:11:56] MR. WARREN: The reason for probing, in my modest way, into such a question, is based on a notion that the attitudes towards such questions modifies the line of action the Negro will take. Do you see what I mean?

MR. BARKER: Well --

[00:12:13] MR. WARREN: His opinion is, or his inclination towards the question . . . . . modified by what he is going to do . . . . . needs action. You can find a strange thing like this: I talked the other day, a few weeks ago, with a very well-known Negro lawyer in New Orleans, who’s a man of fine intelligence and very good education and with instinct, you see, and he’s been a lawyer for one of the . . . . . . civil rights group, and one look at his-- you see that certainly he’s not one of the Black Muslims . . . . . nonviolence; and he finally burst out to say, after a long conversation, that the white man can’t be redeemed; they’re all the same. There are going to be a few, but not many. He said, I’m beginning to feel the Muslims are right. It’s against my feelings and against my philosophical principles, but this is the way I’m being forced, and I’m actually getting inured to it now, and I’m going, not into an organization but into a . . . . . the other group. I hate to say it but this is true.

MR. BARKER: Well, certainly, as you say, as the past few years have gone by, particularly the last year, and Lord knows what we’re going to see this year, in some places, Congress or no, this is-- this is one of the reasons I feel as, I said, that this is going to be heightened for a period. I can feel it myself; I’m that close to it. I’m nonviolent tactically, in other ways this has been a good tactic and it’s worked, and--

[00:14:15] MR. WARREN: You say you’re for nonviolence as a tactic.

MR. BARKER: Yes. It’s not a really part of life, philosophy of life in every respect, and I’ve watched-- well, it was a natural when I first saw people throwing bricks and rocks at people, and you get to the point where I was saying to myself, well, I don’t want to-- I’d like to see some heads cracked myself, if I could just guarantee they’d be the right ones. But of course there are no right heads; everybody’s doing what they feel they have to do, but-- this is the sort of feeling, this was the end result of a sit-in, in other words. But the police protected them while they were picketing. But when they left, there was no protection. That’s very often when the trouble began. And it’s-- I had been in a sense close to the civil rights movement in one way all my life, but mostly as an interested reader, and I hadn’t been in the South for years and I came back, and this happened about four months after I’d been here. It took a week to get over it, and I’d never seen people behave in that way. And when you go through this over and over again and it’s almost easier to forgive the people for throwing the rocks than it is the people who stand by watching and doing nothing, and this is why I think people do begin to feel, well, the white race is worthless for a person. I can’t ordinarily think in terms of redeeming a group of people; these terms mean really nothing to me because I don’t look at people that way. The white race is not worse than any other race. They respond to their culture and their culture’s been particularly unfortunate in this particular regard, and that’s that; I mean-- but certainly I see why people feel this way, and I think this feeling is probably a lot stronger in the North than it is in the South, in the Negro communities.

[00:16:38] MR. WARREN: That apparently is true. And it leads me to an anecdote--

MR. BARKER: There, again, you see you can almost forgive the guy that hits you, but the guy who just stands by who-- and is completely indifferent to your fate, which is what Negroes, usually Northern Negroes, put up with.

[00:16:55] MR. WARREN: He doesn’t know you are there. That’s the greatest assault on you possible. I know one young lady who is very bright, who stands very high in her . . . . . class in Law School (she’s a Negro). She says that she is very optimistic about the Southerner in the South in the relatively near future. With the common history of the white man and the Negro and . . . . . being on the land that long together, gives some basis for human recognitions. Even in the middle of brick-throwing or gun-shooting, some human recognitions are possible, is not, what you were saying, indifferent or detached. It’s real, personal. She says with this basis there’s some hope for a society to come out of it in a reasonable time. She went on to say that what scares her is Harlem or Detroit or Chicago, where she sees no basis for the human recognitions. Does this make any sense to you? She did her bit, she’s been in jail, she’s been in the picket line, she’s had it rough. She’s not just speaking from the academic point of view.

MR. BARKER: Yes, it does, in some ways, and I felt this way before I came back to the South, believe it or not, and I’ve probably been as guilty as anybody else, laying too much stress on the sins of the overt segregationalists and not knowing enough about what was going on in the North and in the West, but it’s questionable to me whether Nashville, for example, would become a community of that sort before it would merely become an American big city and go through what the North is going through now. Now there’s indications in Louisville, for example, of what is going on. There was a very good article in The Reporter called “The Southern City with Northern Problems,” and the mere solution of the knocking down the customary barriers of segregation, the legal ones and the ones that have been so insisted on in the South, does not seem to have produced this kind of rapport that we had hoped for. And I’ve heard Leslie Dunbar say the same thing, that we who think that the South should do better and keep hoping, but there doesn’t seems to be any basis for this. Now I am generally an optimist on the whole situation, but I was thinking, as we were talking about it, when I’ve to put it so far forward, what our Negro’s going to be thinking about in ten or twenty years, I do have a certain amount of feeling that our system may break down on this point, in which there’s no telling what anybody will be thinking about in ten or twenty years. We have come so close to it over and over.

[00:20:36] MR. WARREN: The breakdown of our system.

MR. BARKER: Yes.

[00:20:38] MR. WARREN: In what way?

MR. BARKER: Politically, economically – though this may be in that sense more a contributory factor than a direct one - certainly it’s showing up the strains in our economic system.

[00:20:55] MR. WARREN: You mean the problem of unemployment?

MR. BARKER: Yes, . . . . . differential in unemployment rates. But politically, you see, it’s just really touch and go. Now when the President has to be sending troops down south every once in a while, and you can find northern examples within city governments where the wheels are just practically ground down. Nobody can figure out what to do and the pressures seem to be so evenly divided that nothing gets done. And when you find the incident like the Cleveland School Board, they can’t hardly decide what to do. Cleveland is supposed to be a pretty good community. No white person was arrested for molesting Negroes . . . . . that school. So you might look at it the other way around, maybe the North is going to get the South’s problems too, on this where the real overt expression of a prejudict which has been there all the time but has never really been called into-- well, it never had to be exercised in this fashion.

[00:22:05] MR. WARREN: So that it’s the personal contact . . . . . is that it?

MR. BARKER: Now I know that’s-- that’s been one of the standard gambits of the segregationist-- the people in the North, just doesn’t know what the heck to do with it.

[00:22:16] MR. WARREN: You believe that the segregationist is wrong at that point, then?

MR. BARKER: No, I think that-- well, I certainly think that-- well, you can see it in the-- when you see a map of the first school to be segregated, there’s certainly a correlation between feeling and Negro population density, so you would then-- you could even carry this further, that in metropolitan areas where this density begins to reach a point of-- as it has in Washington and it’s going to in Chicago and in a great many other cities, of course it’s complicated by all kinds of other factors, but where this is a factor, certainly-- I mean after all it would never have come about if there had not been a fairly large number of Negroes. And there’s one statistic I always quote to foreigners and I usually try to quote it to people here. It’s that not many white Americans realize that in the original thirteen colonies one-quarter of the population was Negro, and it was still 14 per cent [percent] at the time of the Civil War.

[00:23:36] MR. WARREN: Yes.

MR. BARKER: I don’t know how many states at that period in the South had Negro majority, but I know there were several.

[00:23:51] MR. WARREN: Alabama . . . . . certainly . . . . .

MR. BARKER: Mississippi still had one in 1930; I don’t know when the switch took place.

[00:23:58]MR. WARREN: Some Negroes in Mississippi will say, and these are to responsible people, that they are lowest in Negroes on the census. There were more Negroes . . . . . proportionately, than the census shows.

MR. BARKER: I expect that’s true.

[00:24:15] MR. WARREN: As you well know, there is statistical argument based on correlation of figures.

MR. BARKER: Well, I heard at one point that any census that could be considered accurate within 20 per cent [percent] was a good one, so I assume we have a good one. But sure, people are lost all over, and considering the type of life of Mississippi Negroes in particular, I would suspect this is true.

[00:24:51] MR. WARREN: As you were saying, one of the standard gambits of the segregationists here is to say to the Yankee: “See, when you get the problem you act the way we act; you were just never realistic, when you didn’t have it yourself. But is there the possibility that as the race difficulties become national, that the Southerners-- some, anyway, will take a different view from that, that they will feel the national problem, the Yankee . . . . . to, I am no longer, I as a Southerner, at the end of pointing, shall we say, of a finger, but now we must deal in a different spirit, a realistic spirit, is relieved, then, of his burden of anger and resentment at being held up as a figure of scorn. Is there some possible release of the rationality because of the fact of the national problem emerging, rather than as opposed to a sectional problem?

MR. BARKER: Well I think -- I would hope so, and I think you can see signs of -- I'm not certain that's the only motivation for it, but you certainly see signs all over of, in many cases, very reluctant, and from the standpoint of Negroes, very pathetic and half-hearted and in a sense worthless change in opinion. In other words, you see this gap of five years or more that what people accepted what Negroes were saying ten years ago, but they haven't accepted what they were saying last month, yet. In fact, I couldn't help but laugh, one of the groups here was actually told, last year: Why don't you get up that nice kind of demonstration that you had in 1960? Well, you know what they were telling them in 1960! But now all they were asking was a "nice demonstration" – they didn't want any rowdy people. . . . . I think this may be part of it and it's so tied up with so many other things, too, with all the other pressures that are pushing, are erasing the division, the industrialization organization -- all the things that were viewed with such alarm from across town in the late 20s. You can't avoid them. I mean they're here. You've got to learn to live with them in every aspect of our lives. And then of course there's the foreign push, and I've always felt, too, that it wasn't so much that intelligent outsiders, anyway, were putting us down for being mean, for being unjust, because all they had to do, brother, was to look around in their own countries. No country guarantees absolute justice, but the fact that we were claiming to be so efficient and here we are, with this wonderful system, and, as I say, we're at the point now where there is, I think, bound to wonder whether it's going to pull through, whether it's flexible enough or not, to make the changes, our attitude, no system, our political system, across the board here. And I think that this is where we really begin to look silly, as I say, to people outside the country. . . . .We claim to sort of know everything, and here we are with what in many of their countries is a relatively simple problem; they've got serious problems of other kinds, and here we are tearing ourselves apart over it. And I think this -- the idea, the irrationality of maintaining this kind of system in the kind of world we live in today, is entering into --. . . . . I hope it may come a little quicker in the South, because they've been thinking about it longer and they've tried every other idea, one of which have worked, in a sense. As vicious as segregation was, it was really a very half-hearted attempt, and if you want to look at it in one way, to do what the politicians said had to be done, of in one sense the fact that it didn't work over the long period. Well, it might have, if the South had been isolated; we don't know -- it's an iffy question -- but it certainly permitted far too much exercise of initiative and ability, to really keep the situation stable, I think.

[00:29:41] MR. WARREN: Even with Bilbo or Natchez Negro boys going to school, the jig is up.

MR. BARKER: Yes, in a sense it is.

[00:29:49] MR. WARREN: Or at least in a sense kids at school. . . . . I've been told by a greater authority are slipping out.

MR. BARKER: His daughter, I have heard. . . . .

[00:29:58] MR. WARREN: Well, that's a -- be that as it may –

MR. BARKER: And, well, that's another factor, too. I mean which is a minor one, I think, but it certainly is there too.

[00:30:07] MR. WARREN: As Frederick Douglas put it, you know, he said: . . . . . the game is over.

MR. BARKER: In a way. Certainly --

[00:30:14] MR. WARREN: -- it starts --

MR. BARKER: Certainly over the long run, that's true. In other words, you can look on segregation as an attempt to prevent what we call diffusion, in anthropology; in other words to --

[00:30:28] MR. WARREN: I didn't hear you.

MR. BARKER: To prevent what we call diffusion in anthropology.

[00:30:31] MR. WARREN: Diffusion, yes.

MR. BARKER: To prevent the transmission of those democratizing items from the majority culture, and it certainly slowed them down in creative endopsychic habit, but as I say, in a sense I think you can call it a failure, if only very pragmatically, because it's breaking down. Well, of course, this is because the South is in -- is part of a larger country which is also part of a larger world, and I think that in the long run this same type of rational approach, the same stresses are going to operate in a somewhat different fashion on the northern situation, because how much longer can we -- can we afford to make paupers that we have to support in this country? It's a ridiculous system. You keep people from getting ahead and then what happens?

[00:31:39] MR. WARREN: It's expensive.

MR. BARKER: It's very, very expensive, and I don't think we'll ever know the true expense of how much of our -- what we put into the police department, relief programs, the waste of tapped talent in general all across the board, is out on the streets making trouble instead of doing something constructive. But this is, of course, all part of what I was saying, was that we are -- our system is certainly under serious stresses.

[00:32:18] MR. WARREN: How much resistance would you find around here in Tennessee to the white sympathizer or the white liberal who wants to move in and take part in the Negro movement? In Mississippi this is very commonly said. I mean people who have been in the very center of it and who are very deeply involved in it, well, I mean people like Robert Moses, we'll say, and as you say and others say it, and . . . . . professor of sociology took me aside and began to explain this to me.

MR. BARKER: Of Jackson State?

[00:32:59] MR. WARREN: Yes, Miss Clark, Dr. Clark, Jacqueline Clark. Do you know her?

MR. BARKER: I met her.

[00:33:05] MR. WARREN: Well, she -- I suppose . . . . . I . . . . . talk about this, it's not just one place. It might be a teacher at Jackson State or it might be Robert Moses or it might be this person or that person . . . . . to come to this point. But outsiders, you know, white or Negro, primarily white, who come in with better educations, most of them, and very soon friction develops, serious friction, in some of these cases, resentment from the local Negroes who are in the movement, not the . . . . . outside, you see, but the people who are active in the movement, and even educated.

MR. BARKER: I can -- there are all kinds of things that can happen. I feel here almost my feeling has been -- and this you find in other places too -- that white people who are presumably friendly to the movement are accepted with a little too -- with not enough criticism; in other words, there still –

[00:34:14] MR. WARREN: Not enough criticism from the Negro, you mean.

MR. BARKER: Yes. There is still enough, it seems to me, of the old feeling, that well, we're glad there are some of them that are decent, or however you want to put it, that they are not judged, in a sense, the way they would judge their neighbors, and of course it's very difficult to, in one way. You haven't been brought up, from their point of view, to judge white people in this way. For all the fact that it's very true, I think, that Negroes know more about white people than the other way around. There are still areas of white life that the Negroes have not been able to see with any clarity. And I haven't seen any cases of real friction, though I know certain kinds of white behavior which would certainly bring it about.

[00:35:07] MR. WARREN: From people that -- who have come in to help.

MR. BARKER: Yes, and I -- as a matter of fact I can see it myself, I resent certain white people that drop by here with wild ideas, and well, they head for every trouble spot there is. You'd be surprised -- this Louis Jones; have you met him, the sociologist?

[00:35:33] MR. WARREN: I know who he is, but I've never met him.

MR. BARKER: Well, he thought that the wandering minstrel sort of thing -- when the trouble was going on in Fayette and Haywood county [County] -- all kinds of strange people wandering around there. Some of them end up doing good work and some of them are worse than no good. You'd be better off without them. Now with regards to the school situation, I suspect that -- I don't think that there's much of it here, but I could see how there's a certain amount of resentment could spring up if only in a sort of envy. Well, if I'd really been able to get the kind of education this guy did, I'd be a hell of a lot better scholar. Or something like this.

[00:36:20] MR. WARREN: The breakdown, as far as I can make it from these various conversations in Mississippi, on this topic is -- of course I didn't initiate it, must be volunteer, is something close to the surface, you see.

MR. BARKER: Yes.

[00:36:31] MR. WARREN: One, what you're saying this kind of envy, general envy, you see, in other words, resentment about inferior position. The second specific resentment is because the outsider, probably better trained by and large, tends to drift into a command position, if not top, at least, you know, command post here and there, and this puts him quickly in the position that some Negro has been yearning for human . . . . . and expecting, perhaps. Then, as Dr. Clark said; Dr. Jacqueline Clark, it's the girls. She said that a lot of the Negro girls tend to take up with these outsiders, either the white outsider or the Negro outsider -- You've got a romantic . . . . . of characters who come in. This has been a matter of real trouble -- and there are some other tie-ups on that.

MR. BARKER: I was thinking about the women, in particular. In a sense, you're damned if you do, and you're damned if you don't.

[00:37:33] MR. WARREN: That's right. No . . . . .

MR. BARKER: If you hold yourself aloof, at least, that's how it's assumed; if you don't date locally. If you do, they holler. Somebody's not going to like it, so --

[00:37:42] MR. WARREN: There's no way out of that one.

MR. BARKER: You just operate the way you feel like operating. There are things, too, that a lot of white people are -- come in to the situation. They think they know what it is. They -- I've never heard a Negro complain about this that I've seen; this is another point that I haven't really thought too much in general terms here. They are very upset when they find Negroes behaving just about the way they would behave in that situation, their very romantic approach to the thing, and sometimes it takes a while for this to get over. Well, during this period, they're likely to have rather extreme standards of behavior for Negroes. In other words, that they should be putting their nose to the grindstone and. . . . . NAACP instead of out getting drunk or something, and there are all kinds of things; they're usually more amusing than anything else, because with good will and a reasonable amount of good sense, this -- I think usually will get straightened out; . . . . . it depends so much on individual cases. I'm interested -- you must be able to get pretty deep with people with -- it did begin to come out in your conversations; but, as I say, from -- I'll come back to my original thing, because I want to stress it, I do feel that by and large, there's not enough suspicion of white people by Negroes. We had Billie Sol Estes people ask me who he was. I didn't care, really who he was. All he was was a wealthy white man who was with them today, and I was pretty upset about it. Now I could bring myself to being unpleasant by running around screaming with horror, but I didn't. I just said, well, he's a very unsavory character and let it go at that.

[00:40:00] MR. WARREN: Another type of resentment that was reported to me is - - was reported by Robert Moses . . . . . type of fellow, a character. But there's resentment against a certain sentimental kind of white attitude that is the white man who wants to move in and adopt, to go Negro, to adopt a certain vocabulary, to adopt certain stances, to adopt certain attitudes, to get the lingo of the music, get the lingo of this, the lingo of that, and he said this is mixed with contempt rather than as much as with resentment, mixed with contempt as with resentment by people who didn't really have a lingo, didn't really have a dissent, didn't really even have a feel of what they were trying to move in on, with some contempt and resentment at the fact that the white man's trying to take our boy to a nunnery(?). Does that combination of attitude --

MR. BARKER: Yes, but I have a -- you see that -- and frankly, sometimes -- you don't know what to do. You do have, just like on the question of women, you have the feeling that whatever you do, some people are going to think you're stilted if you don't lapse into it, it seems to me, the current language; or they'll think you're trying to be insulting/silly. And then they know darn well that a man's not going to turn himself into a Negro in thirty days or thirty years, for that matter, if he wasn't born one. This is just -- well, you can see it over and over again, you're dealing with a different culture and you learn that culture in your childhood, and if you don't learn it then, you never learn; you never will, without the fact that a person, without doing Mr. Griffith's trick, you're never going to look Negro enough.

[00:41:57] MR. WARREN: There's one other aspect of it -- though this has not been remarked on to me; but I wonder about it, some sort of contempt or distrust, what I think -- . . . . . pathology of the left, people whose motives clearly are not anything except a kind of distortion of personality that brings them. . . . . integration, seeking aid and . . . . . from the other underprivileged-- I'm hurt too and you're hurt too; we'll club together, in some sense. That -- you know what I mean, of course.

MR. BARKER: Yes.

[00:42:30] MR. WARREN: And I've heard -- this is the way Ralph Ellison once would say, you see his angers had kind of fagged liver, you know. You know. . . . . clubbed up, and out of his own infirmity, moves in to club with the Negroes that we-all-hurt-together. . . . . . in an nonunderstanding [non-understanding] world. That sort of illness, this kind of resentment comes under that.

[00:43:03] MR. WARREN: There's probably some of that, too, as far as –

MR. BARKER: Well, there's plenty of -- of course –

[00:43:07] MR. WARREN: I don't mean . . . . . homosexuality . . . . . all kinds of . . . . . pathological . . . . . elements.

MR. BARKER: Well, I think there are a lot of Negroes quickly sense these things in people when -- and if this seems primary and the commitment to what's being done is secondary, there will undoubtedly be contempt. In other words, people have come down to take a freedom ride to salve their emotional problems. It doesn't work, and they know it right away. I remember hearing a specific example, just what you were talking about. We're a little bit more immune to that here because this isn't one of these things where people come and go and people get to know you, see you around in this community. And then of course I don't know, although-- here again I think that I'm probably . . . . . and doing a lot more, although they're happy, they're around other white people in this community that are in organizations like the National Committee for Relations Council. I think they feel they're nice to have around. I don't really think they really do very much, but they -- this wouldn't come in on that, you see, because these well-meaning people don't always want to know.

[00:44:30] MR. WARREN: Ordinarily well-meaning . . . . .

MR. BARKER: But you see the assumption that because I have a problem whether it may be a big one or not, therefore, I know what your problem is, I feel the way you do, is an arrogant one, and if people come in with that it's undoubtedly they're going to have trouble.

[00:44:49] MR. WARREN: It's probably even worse if they don't know they have a problem, and acting unconsciously on that motivation. Do you see the differences or similarities between the old abolitionism and the present situation on psychological or other grounds?

MR. BARKER: I hadn't thought much about that. Well, I guess I can get -- take the easy way out and say I can see them both.

[00:45:28] MR. WARREN: . . . . .

MR. BARKER: It would be pretty difficult to compare historical movements. Now working in an organization, as I do, which has its roots in the American Missionary Association, I guess I should say I see some similarities, the commitment of certain branches of Northern Protestantism has never wavered on this score. There are so many other historic facts . . . . . different.

[00:45:55] MR. WARREN: Back home.

MR. BARKER: Hmmm?

[00:45:57] MR. WARREN: Back home, except at home.

MR. BARKER: Oh, yes, yes. Well, you're right, there. I do not stem from that background, myself –

[00:46:08] MR. WARREN: I'm kidding, you know.

MR. BARKER: Well, when one hears about Mr. Higgins' private social life, and so forth, at this point. Beyond that, there's something I ought to think about now, but I can't really –

[00:46:25] MR. WARREN: I don't know what I think about it. I don't even know if I know enough to have any very considered opinion about it. I must say on the whole at a guess just on my slight acquaintance with this business, it seems to be now two differences. I'll try this anyway. I don't know whether I . . . . . believe it or not. There's probably be a . . . . . in the abolition group/movement.

MR. BARKER: That is one thing I've always wanted to say, that I was certain that one of the similarities was that you got a lot of strange white people in both of them.

[00:46:57] MR. WARREN: Yes. More of them -- you can get, you know, a galaxy is really, you know way out in left field, and a lot of the others were there too. There's more, obviously than many people who are now concerned with -- that is now more central to -- the issue is more central to a standard social problem.

MR. BARKER: I think one thing that's not really relevant to the particular question you asked, one of the things that enters in here, is the recent convers to the movement, so to speak, the white person who has somehow or other shaken prejudices he was taught in some fashion or other as a younger person, and just like any self-made man he can never quite understand why other people can't do it too. It was the same -- it -- the same kind of attitude, and . . . . . person in this case where you'd like to have him, but it doesn't work for a very clear understanding of the situation that you're dealing with, and I think that the Negroes despite the fact that I see all kinds of evidence to the contrary, somehow do have a -- despite the rhetoric we're used to at mass meetings, somehow do have a perception of this as a conflict in social systems, much more than a lot of white people do.

[00:48:38] MR. WARREN: They see, you might say, the dynamics of it more clearly than the white man, who tends to moralize it.

MR. BARKER: Yes, who sees it as a -- though as I say, the rhetoric is you've been to Negro mass meetings; you certainly hear things, but in terms of white and black, very frequently. But, as I say, I would suspect that a clear understanding of this, even my understanding, with all kind of training I've had, which should make me see clearly, or things that I just sit and wonder about.

[00:49:07] MR. WARREN: Such as?

MR. BARKER: Oh, how could it -- I can't understand how it came about, how it -- I can't understand the depth of white feeling on the subject, myself.

[00:49:25] MR. WARREN: The segregationist feeling.

MR. BARKER: Yes. You see I fall into using the terms very inaccurately here. And other things too, but -- in fact some of them there I can't even phrase the questions very well, I just know there's something here that if it doesn't work out well, some nice little scheme that you can't take out of cultural anthropology. But, as I say, I do have the feeling that -- rare, though a clear understanding of this as a question of culture change, whatever you want to call it, that there may be a little more subconscious understanding of this on the part of the Negroes and on the part of whites who are in the movement, so to speak, thinking of people in terms of activists, so to speak. -- I don't know, I may be all wet.

[00:50:26] MR. WARREN: How would you respond to a notion such as this: You take the part of the situation of the Negro and his loss of direction and his self-respect -- he was deprived of a culture, whatever culture he had; he was lost. He was lost. He was a man without a mooring, without any identify, and by reading the right books or talking to the right people, part of the situation now -- and he has recovered his identity, in the sense of a place within a culture and an acceptance of his role as a Negro, a seeming senior role as Negro. Now let's take the same amount of thought applied to the white Southerner, with certain changes, the white southerner feels he has an identity as Southerner; he also has identify as American, but he feels his identity as Southerner, as many of them really do -- 'our way of life' and all this sort of thing. Now if he's uncritical and doesn't know very much history, he's inclined to buy the package of the way of life, including what is -- the present package of segregation; things are very different from anything in the past, of course. A lot of changes have taken place. So he's really, in a sense, not merely keeping the Negro in his place; he he's trying to keep himself in his place, trying to keep his identity -- He feels his identity is threatened – not merely by the fact of a change in relation to the Negro, but this is a symbol for -- one of a tissue of symbols of his basic identify. This is part of his own role. He's acting out sometimes to keep his identity, to keep his cultural role. It's not just an isolated/isolation "what do I think about the Negro?" Or "what do I think about segregation?" even. Except that, of course, that with segregation means as -- is part of a pattern of thought instinctively or accepted without criticism, as his identity, his role . . . . . do you see what I'm driving at?

MR. BARKER: Yes, I do, very clearly. I can -- if I had that little machine with me on several occasions during our demonstrations, I could document it. There's a surprising lack of, well, not lack, there's, to me it's a surprising lack, but after all it's surprising, there is much less of what you call racial vituperation among white bystanders, and I would expect there is a tremendous amount of nostalgia and the feeling that the world is just gone made, there's no way-- there's no place to stand, anymore.

[00:53:14] MR. WARREN: That's what I'm getting at. That's the –

MR. BARKER: This wouldn't happen twenty years ago, and I guess the time has been taken over, of course . . . . . always gets into it, but this is just a nasty word for the future, to a lot of people.

[00:53:28] MR. WARREN: This is a fear of disorientation.

MR. BARKER: Now of course social changes always brought down the people it is happening to, but in our urban centers, where most people live today, it's much more on the surface, there are more ways to handle it, in a sense. You see changes much more rapidly. The south is seeing them too, but the change that has come has moved at a slower pace, it's been harder, and it's paradoxical that the more changes this year, there'll be twice as many next year, but that doesn't make it any easier to take. As a matter of fact he may be so upset by the changes of this year that he'll be completely floored by one that comes in next year.

[00:54:26] MR. WARREN: Now what I'm getting at is this: As a corrolary [corollary] of that or a consequence of that, if you can indicate to your Southerner that to be Southern doesn't necessarily involve segregation.

MR. BARKER: I thought . . . . . tried to say –

[00:54:49] MR. WARREN: He is . . . . . but this is the old story of Thomas Jefferson, of course, . . . . . to integrate this bloc conception, the general notion into its elements, that your identity does not depend upon that, even your identity as a Southerner, that the attack is not on, say, you're an American first. All right, you're a Southerner, but what does being a Southerner mean? Do you see what I'm getting at? It doesn't necessarily mean that, that isn't necessarily part of the picture. That's another part of the picture. Is there any validity in that approach?

MR. BARKER: I think -- well, as I -- I would say in the long run, no, for the simple reason that the -- not because, theoretically it couldn't be true at all, except that I do have the feeling that the other things which are considered part of the Southern way of life, are casualties just as much as segregation is in the modern world.

[00:56:05] MR. WARREN: Some of them are, yes, sure, but you can . . . . . a different . . . . .

MR. BARKER: But I certainly think it's -- it's a short-term long-term thing again, just like my comments on black chauvinism. I think it's a good ploy; I don't know how well it's working. I would suspect the people, like Mr. Dann would get pretty discouraged, and the people that -- it's corollary with those men with the belief that the South has within it to be better than the North, on these questions. And I don't know -- I --

[00:56:45] MR. WARREN: Some Negroes say that. Charles Evers said that . . . . . otherwise . . . . . He said I had no idea of segregation . . . . . whatever that means . . . . . And many Black Muslims say that.

MR. BARKER: Oh yes, this is a -- well, it's almost a standard response, I think, now. I don't know as it's all very well thought out, I mean.

[00:57:19] MR. WARREN: I don't know. I had no idea, but . . . . . to hear a Negro saying that and not taking him at his word, if he feels that, and try to explore what he means by that so as far as I can in my blundering way. I think how Evers started it, if you're interested, he said insofar as . . . . . around, of course there always are. But that by and large these sit-ins have a sort of simple code and one thing that they admire is nerve, is courage, so that if they don't admire it they feel they ought to admire it. And they feel trapped into acting courageously, even if they're afraid. They're caught in this-- they have an old-fashioned code about this. Therefore, out of . . . . . if the Negro stands up to him he begins to sit up. They guy's got nerve. He's got a working basis for that right there. He's not afraid. He may be infuriated at the fact, at first, that the Negro's not afraid, but he begins to respect him. This is the base of conversation, it's a base of dealing with a man because he respects you, and simply . . . . . in dealing with you by this raw courage. Second, he says that these people tend to keep their word, that when they cross the line and make an agreement on some point, they tend to keep their word. They cross the line when they make the agreement, at first, but the Negro having crossed, he says, but once they get around the table and take up negotiations, he says, we're going to be fair because they'll keep their word. They won't try to trick you, because that isn't in their approach to things; once they've crossed the line. Now I think you will agree.

MR. BARKER: Yes, I was thinking that certainly some of the most astute and trickiest politicians this county has produced have come out of this background.

[00:59:25] MR. WARREN: Oh, I'll say, I mean these are politicians . . . . .

MR. BARKER: And I would really like to believe this, of course, of everybody, but I really can't see it much here any more [anymore] than anyplace else, it seems to me, that -- I will go along wholeheartedly with the first part of it, though it's the sort of thing that I think that the individual white Southerner has to have a personal knowledge of, because this is, of course, one of the bases of the whole sit-in strategy was that by not hitting back, by taking it, you made these people respect you. Well, I'm not also sure that's true. Some people like to beat on people. They don't give a damn whether they beat back or not, if they think they can get away with it.

[01:00:22] MR. WARREN: Some people do that very well; also, some like to be beat up.

MR. BARKER: Yes.

[01:00:31] MR. WARREN: Or so I'm told. I don't know what-- I don't think . . . . at all by Evers' remarks, as a matter of comparison, of course, he hadn't been around. You've been around . . . . . making it stick, but the fact may not be true there. I thought there was was of some significance, but you have to believe. Right or wrong you have to believe in something . . . . I've heard that. I've heard here in Nashville of people who had to do something with the sit-ins negotiations or had some information about them, that their dealings with the Southern white owners and local owners was much simpler, much more clearcut [clear-cut], much more straightforward than that of outside owners.

MR. BARKER: That's certainly what I know about it, it's been true and it's still true today. Part of it, of course, is just that they're around, that you have people right here who can make the decisions. Part of it is that they don't bring in all kinds of bureaucratic problems involved. In other words, if the store's a chain store they might be very willing to open up in Nashville if they're got a branch in Jacksonville, Mississippi too, and this is going to create problems. I think this was what Woolworth's got hung up on, because, basically, Woolworth's doesn't care one way or the other; they have no personal commitment, any point of view on this, but they felt they would get into all kinds of trouble in other areas.

END OF TAPE I

(Mr. Carroll Barker, Feb. 15)

Collapse

TAPE 2 Searchable Text

Collapse[These digitzed texts are based upon typed transcripts created in 1964. Errors in the original transcripts have not been corrected. To ensure accuracy, researchers should consult the audio recordings available on this site. Time stamps are included in the retyped transcripts to aid in this process.]

[Note: "Barker” is an incorrect trancription that appears in the original document. This interviewee’s last name is Barber.]

(CONTINUATION of conversation with Mr. Carroll Barker, Feb. 15)

TAPE 2

[00:00:53] MR. WARREN: Let's go on with Memphis.

MR. BARKER: Well, I don't really know enough about it. I got stuck there in the snow, over Christmas, and I landed on one of these people and stayed there. I'd heard about it and I always wanted to go down there and see a little bit for myself. But the quality of life, you might say, is much more segregated there, than it is here. There are a few white liberals, they do have a struggling little chapter of the National Community Human Relations or the Tennessee Council on Human Relations, but I was very impressed, over and over again, with this.

[00:01:39] MR. WARREN: Who this?

MR. BARKER: Vasco (?) Smith.

[00:01:40] MR. WARREN: . . . . .

MR. BARKER: Well, Willis started it. And Mabon Williams. He and Willis dreamt it up, and I got in on making a reservation at the Holiday Inn downtown for Smith, to make a test case, and I picked him up at the airport and we went there and he was refused, of course. Then the local Unitarian minister went in afterwards to verify the fact that they did indeed have rooms when they said they did not, and he, as Dr. Smith has said, any number of times, he said: "You know we just don't have people like you in Memphis."

[00:02:20] MR. WARREN: Like the Unitarian minister?

MR. BARKER: And myself. I said, well, it does seem strange to me because I'm sure we have a great many here in Nashville. I may be wrong, but I think we do." So that, as I say, the -- well I can't think of a better term, but the quality of Negro life is much more segregated there on the middle-class level. Now of course, I don't suppose there would be too much difference on the lower-class level.

[00:02:48] MR. WARREN: Did you see the editorial in the Press Scimitar this week on the civil rights bill?

MR. BARKER: No.

[00:02:57] MR. WARREN: Complete endorsement, a very positive endorsement, said that if the Senate doesn't pass it immediately, it will be a mandate of the people.

MR. BARKER: Well, that's stronger than the Tennessean has been. They had one but it was -- it wasn't the lead editorial and it wasn't that forthright.

[00:03:13] MR. WARREN: This was forthright, there's no possible shadow of a doubt about this. There's no ifs, ands or buts, and it was prominently displayed.

MR. BARKER: Well, this was no longer what you said Everts [Evers] had said, that most people commit themselves on that. Because both papers at the beginning were not very helpful at all.

[00:03:32] MR. WARREN: What I've also heard said is that this may have some tie-in with the local political situation.

MR. BARKER: Well, they endorsed -- both papers endorsed Negro candidates and . . . . .

[00:03:44] MR. WARREN: Yes, it's always a question of juggling/jockeying for position, with the Negro vote. I don't know how this is argued, because I don't know enough about the tie-in or not, but this is one of the suspicions in this, I've heard. That was editorial.

MR. BARKER: Well, Memphis politics is very devious locally, I don't pretend to understand it but currently all kinds of things are happening in Tennessee now because of the Negro vote. That's apparently -- and almost everybody accepts the fact that if it had been withheld from Clement he would not have been governor, and if Rossbass has editorial ambitions, so he voted for the bill. Richard Fulton has been very forthright all the way along in favor of civil rights legislation, and I hope it doesn't kill any . . . . .

[00:04:41] MR. WARREN: How old is he?

MR. BARKER: In his 30s, I think.

[00:04:45] MR. WARREN: Well, he can plan for the future, then.

MR. BARKER: He has strong labor support and he has the "Tennessean" solidly behind him.

[00:04:58] MR. WARREN: What line has the Banner taken on this?

MR. BARKER: Oh . . . . . very vicious, and they lose no opportunity to discredit it or anybody that's for it, as often as they can.

[00:05:14] MR. WARREN: That was the reason that I thought it was true, it was true in the past; and I hadn't thought of it in the last --

MR. BARKER: They wrote all about Bayard Rustin's peccadilloes in The Banner, and The Tennessean just glided over things like that, you know.

[00:05:26] MR. WARREN: What sort of peccadilloes?

MR. BARKER: Oh, he's – has some kind of moral events in Pasadena. I'm not telling anything on the man; I've never met him, but I was -- it is documented, though, and The Banner went on and on about this during the March on Washington, and they've been -- they reluctantly accept changes once they're made here, but they always fight them, and The Tennessean exerts influence behind the scenes very often, very little. They don't editorialize very often.

[00:06:00] MR. WARREN: But they have a behind-the-scenes influence in favor of quotes rational change?

MR. BARKER: Yes. Yes, an awful lot of things can go on now, with all that pass through Jack Siegenthaler's office. For instance, John Lewis -- have you interviewed him yet?

[00:06:17] MR. WARREN: No, I have met him but I haven't talked with him. I met him . . . . .

MR. BARKER: He'll be back here this week. He has some trial coming up again. I just heard he'll be back. He wanted a particular young businessman here, and if you ever had the time . . . . . Inmanoti, it would be worthwhile interviewing him. So he tells Jack Siegenthaler that Inmanoti was outstanding . . . . . of the Mayor's committee, and in a few days Inmanoti was accepted. Well, there may have been other people, that wanted him on there. But in any case, I imagine Siegenthaler had something to do with it.

[00:06:52] MR. WARREN: The original headquarters is down in Atlanta, isn't it?

MR. BARKER: Yes. He's president of SNCK now. You see he was head of the students here during the time most of the time I've been here, and was heavily involved from 1960 on right here.

[00:07:07] MR. WARREN: There's a section in Baldwin's last book to this effect, rough paraphrase: according to the best testimony, that of those in the embattled South, the Southern mob does not represent the majority of whites. . . . . but will represent the white majority. But it will feel a moral backing. Does that make any sense to you?

MR. BARKER: I think it does. Because you -- this is almost a truism now, that where the people run the show, in whatever-- whoever they happen to be, wherever they happen to be in a community, say there will be no nonsense, there is no nonsense, by and large. Now Nashville's a little bit in between, so you can find good illustration of both there, which in a sense proves the point. In other words, there are times when the officialdom has been lax, there's trouble. When the officials have been forthright and says we're not going to have any trouble, there isn't any trouble. Now the violence I mentioned, soon after I came here, the mayor had a tremendous number of problems. He was forced, with this white metropolitan government which he did not want, the police force was pretty demoralized apparently because of this, because they didn't want it either, he told them they didn't want it, and things like this were happening. Then of course other things entered in too, last spring -- well, things were almost more than anybody can handle, but we had just gone over the metropolitan government and nobody quite knew what was going to happen, you know. The mayor was uncertain how far his authority ran in some questions, and he had inherited this deplorable police department. They did, by and large, a pretty good job, but still there was not enough obvious open pressure by the leaders of the community; this was a disgrace to the city. The Tennessean didn't say enough. The Banner had headlines like "Police Quell Negro Attack," which was somebody wrestled with a policeman's billy club and that's a Negro attack. Well, the behavior was certainly not nonviolent in many cases, but total misrepresentation of the situation. If you come from -- if you read that happening in Cyprus, you can imagine what kind of attack you would imagine it would be. And I think that by and large this is true; I saw this out West before I even came here. I was in Arizona when it got in under the wire. Arizona desegregated in 1951; they had a rather patchy kind of segregation, anyway. It was obligatory in grade schools and permissive in high school, and the only communities where they had any trouble was in the communities where the mayor said, well, geez, I don't know; we're likely to have trouble over this. In communities where they said this is the way it's going to be, no trouble.

[00:10:35] MR. WARREN: Some people, of course, are going to say, to this remark of Baldwin's that silence gives consent. The mob is actually acting out the will of the majority, which is silent because it doesn’t' have to speak . . . . .

MR. BARKER: I think the mob thinks that. I think that's the important factor, that if the police get no instructions, they will (it has been said, too, in a Southern community, they will assume an attack against custom, even when it's not against the law, is an attack against authority, and they will behave accordingly. If they have been told otherwise, they will behave in a different fashion.

[00:11:13] MR. WARREN: There's another interpretation, different from that one, that the mob doesn't represent the will of the majority, but the majority is so fragmented, so divided, it has no point or focus for a statement of feeling or a statement of values. Let's say you have 50, 60 per cent [percent] against that the mob is doing what it stands for, if there's no point along there where you could have a strong statement or group action, they call it too much spread in that majority. It's a negative majority; it's not a majority for something, it's a majority againstsomething. It has no point or focus.

MR. BARKER: Well, I think both have probably been true, I wouldn't attempt to say which is probably what you get, but I would certainly agree that the mob doesn't represent the majority of feeling; at least in the areas where I'm very familiar with it. It might very well, in some black belt county. But even there, I would have serious doubts. I'm not quite so sure in thinking over the quotation that I like the phrase "moral vacuum" very well, but at least I understand, I think what he's getting at. I'll go along with it.

[00:12:34] MR. WARREN: I'm not sure I know precisely what he means; I have a general notion what he means.

MR. BARKER: So I'll just leave it at that. I can get moralistic about race relations all the time, even though I -- but I have learned it doesn't help very much. If, however, the people who present to be the guardians of the community's morals keep quiet (and this, of course, includes the church and even the administration), Americans expect their leaders to make more pronouncements as a part of political life. But this I will go along with completely. In other words, there's a moral vacuum in that sense that these people do not speak out.

[00:13:20] MR. WARREN: . . . . . in a survey of New Orleans, the advisory commission for civil rights, they said, what I read of the report, that not a single person of any significance as a community leader, uttered . . . . . New Orleans crisis/crises. Not one, would show himself.

MR. BARKER: Well, New Orleans, I thought was so bad that I'm inclined to go along with Thurgood Marshall's charge that the school board picked those schools deliberately. That may be very unfair, but in other words, they picked the places where they thought they could get the most commotion. I say this seems very unfair, but considering the situation, it may very well be true.

[00:14:01] MR. WARREN: It said New Orleans, though, that the first day or so there was no trouble at all; it was only after it was worked up the second day, that you got it wasn't spontaneous reaction, it was a devised reaction.

MR. BARKER: This is true, too, because the mobs just don't happen. You could see it on a very minor scale here, there is always a few young what do they call 'em, hoodlums, a little bit unfortunate young white men wandering around downtown, probably they'd been downtown looking for a little mischief anyway, these old men on the sidewalks, egging them on and patting them on the back, figuratively or literally, and even then it took quite a lot to build up to action. You know these things don't happen; those women didn't all decide to go down there and scream out the same damn thing at the same time. Somebody was behind it. Who, I don't know. Well, that of course is why it's so important in these cases, if people who should, speak out . . . . . because that very often scares the people who are going to get the mob out, it makes them

feel it's not going to be very well worthwhile venture.

END OF TAPE

Collapse