Gunn lists several Cleveland companies that employ and promote African Americans, and he also discusses black-owned businesses within the city. Gunn considers the current leadership of the civil rights movement, both in Cleveland and elsewhere, and he describes participation in recent school boycotts around the country. Gunn discusses the quality of public education in Cleveland and suggests that equalizing educational opportunities for schoolchildren may be more important than integration. He also discusses the position of upper- and middle-class African Americans within the civil rights movement. Gunn describes in greater detail several of the school demonstrations in which he participated in Cleveland, and he also considers a distinction suggested by Warren between general demonstrations and demonstrations with specific targets. He also discusses northern white reactions to events in both the North and the South and what he views as differences in race relations in the North and the South.

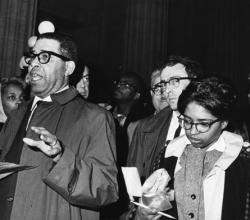

Richard Gunn

Richard L. Gunn (1925-1976) was an attorney and civil rights activist. A long-time resident of Cleveland, Ohio, Gunn was actively involved in the struggle to integrate Cleveland's public schools. During the 1960s he served as counsel for the United Freedom Movement (UFM), an education commission that advocated for the integration of Cleveland's public schools, and he helped negotiate with the Cleveland Board of Education on behalf of the UFM. In 1964 Gunn and the UFM delivered a list of demands to the Board of Education that called for an end to school segregation and also advocated for the hiring of African American teachers at previously white schools. Gunn was convicted of violating Cleveland's trespass statute in 1965 after he participated in a demonstration in front of City Hall. Gunn also served as president of the Cleveland branch of the NAACP. In addition to his work with civil rights organizations, Gunn served on both the Board of Trustees and as the Chairman of the Law in Urban Affairs Committee of the Cleveland Bar Association.

Transcript

TAPE 1 Searchable Text

Collapse[These digitized texts are based upon 1964 typed transcripts of Robert Penn Warren’s original interviews. Errors in the original transcripts have not been corrected. To ensure accuracy, researchers should consult the audio recordings available on this site.]

Richard Gunn – tape #1 – p. 2

RPW: Why that – why did they do that?

RG: Well, Cleveland Electric Illuminating Company has a very fine hiring policy. They have had a very fine policy of upgrading these roles recently. There was a young Negro fellow, Carl Chansler, who was upgraded to the position of assistant chief attorney in one of the sections, and this was a first with the Illuminating Company. You have another young Negro fellow who has a fairly high position with the Illuminating Company, and there are some others in the lower echelon in the company. At Ohio Bell Telephone you have a Negro who is one of the supervisors down there, Lowell Henry, who was formerly in the City Council of the city of Cleveland, and you have several girls in the supervisory categories on the lower level, on the operating level, and as far as most of the companies, you cannot point to them with the same type of record as you do with the Ohio Bell Telephone Company and at CEI – Cleveland Electric Illuminating Company.

RPW: How much Negro-Owned business is there here?

RG: Well, we have in Cleveland quite a few Negro-owned businesses. I was formerly the president of the Cleveland Business League, an organization basically comprised of Negroes in business, in the professions and in the various trade categories. And we have at this time – I'm quite sure – we had a study made about five or six years ago – there are over two thousand Negro businesses and professional men and tradesmen in the city of Cleveland. Many of these businesses are marginal businesses. Some of the businesses are rather substantial. We have the Cleveland Sausage Company – Mr. Credon died last year, but he headed up the substantial business here in the sausage manufacturing field. We also have Couch's Sausage, and this is a young man who has a good business going. We also have a Savings and Loan Association here – Quincy Savings and Loan – I think they have assets of close to six million dollars – this is a Negro owned and operated business, though there are some white stockholders – they are in a minority. Then you have the Dunbar Division of the Supreme Life Insurance Company – they're operating here. Of course, Supreme bought out the stock in the Dunbar Life Insurance Company, a company started here in Ohio. And as far as the large Negro businesses, you don't have the large substantial businesses that we should have in the community. However, we do have several Negro insurance agencies, whereas ten years ago you did not have one Negro insurance agency because Negroes weren't able to obtain agencies in this city. My law partner is a lawyer but he devotes most of his time to the general insurance field, and he has been in this field for ten years, and he often belabors the fact that he wished that he had started in the insurance business much earlier, but unfortunately he was unable to start in the field until in the early part of the '50's because no Negro was able to get an agency.

RPW: I was talking with Adam Clayton Powell the other day, and one of the first things he said was, the old organizations, the old leadership is finished. They are through. How does that strike you?

RG: Well, I would like to state that I may share his opinion partially that they may be through. I don't think that there is any reason for this other than the fact that they are old, and as you know when you have labored in the vineyards of civil rights and other organizations for many, many years you tire of this, and when you reach a certain age you just do not have the vim, vigor and vitality that you formerly had. Now –

RPW: What about CORE?

RG: CORE? You mean the – this is a young people's organization, but I think that CORE –

RPW: He said the same thing about CORE and about SNNC – all together – the big five organizations.

RG: He said – what did he say about that?

RPW: All together – they are not significant any more. That's what he says.

RG: They are not significant? I think Adam Clayton Powell is somewhat wrong in this approach and in this statement. However, we did have a situation to develop here in Cleveland within the last three weeks, when the movement in Cleveland got to the point that – where there were demonstrations several weeks ago – one of the largest dailies in the state which is situated here in Cleveland wrote an editorial asking where are the Negro leaders, the responsible Negro leaders. And they proceeded to name these responsible Negro leaders in their editorial. Now, it just so happened that most of the names of the individuals named were the traditional Negro leaders that have been looked upon by the white community as leaders in this community –

RPW: You mean locally?

RG: Locally – locally – and they felt that the responsible Negro leaders would come out and object and not agree with the techniques being used by the younger fellows – I guess I could be considered one of the younger fellows in this movement in Cleveland – but we did have a meeting – these so-called Negro leaders called a meeting – twenty-five of them – about thirty of them gathered at the YMCA, and these were your traditional Negro leaders. Some of them were – there were two judges there, and others who have been on the scene for years. It just so happened that a few of us younger fellows were intruded in this meeting, and as a result of that meeting we discussed the school boycott that was to take place in the city of Cleveland. Of course, the newspapers were opposed to the school boycott. And we discussed other things. But as a result of this meting, all of the these leaders – if they were to be called leaders – I am not a leader but I was at the meeting – but we all agreed that evening that the school boycott was a good thing, we went on record as approving and endorsing the school boycott, we went on record as approving and endorsing the program of the United Freedom Movement, which I imagine you've heard of, in Cleveland. And this release was released to the newspaper, and all these men, with the exception of one, assented to the fact that their names could be included in the news release, and of course I am quite sure this dispelled any thinking on the part of the white community that the so-called responsible Negro leaders, who were the older leaders, were not behind the United Freedom Movement. It pointed out to them that we were all together, including the traditional Negro leadership in the past, and we all joined hands together and they were solidly behind the entire movement here in Cleveland.

RPW: That would not be true in New York, of course. look and see – I mean, for instance, CORE suspending two chapters in New York, the Brooklyn and New York chapter, and the whole struggle about the boycott there. (talking together)

RG: … second boycott in New York City.

RPW: And the CORE – they both did. (talking together) And they suspended Bronson's outfit, you know.

RG: I know they suspended Bronson's group.

R PW: There's anything but unity in a situation like that.

RG: It's true – very true.

RPW: Now, what is the moral of that story?

RG: In New York City?

RPW: Yes.

RG: Well, I think that this was probably the result of the organizations in New York wanting to withdraw and not be associated with the more radical movement developing in the Brooklyn chapter of CORE. I think that the NAACP withheld from the – withheld support from the second school boycott in New York because they felt that this was an irresponsible move. But I understand from very good sources in New York City that the NAACP is now unhappy and they feel that they were wrong in not supporting the second school boycott in New York City, because the second school boycott was not a success. Another typical example of this is what happened in my home town, Kansas City. Kansas City had a school boycott the same day we had a school boycott here in Cleveland, Ohio. In Cleveland, Ohio, between 92 and 95 percent of all Negroes in the city of Cleveland stayed out of school that day – about 65,000 children. In Kansas City, the NAACP withheld their support from the school boycott, and there were only about 40 percent of the children who stayed home from school in Kansas City, Kansas, on the same day we had our school boycott here. I feel that the fragmenting of the efforts by the withholding of support by the NAACP minimized the effectiveness of the school boycott in Kansas City, whereas in Cleveland all of the so-called Negro leaders were behind the movement, the boycott, the NAACP was in support of the boycott, CORE, Freedom Fighters and all the civil rights in this community, including many white organizations supported the school boycott in Cleveland, and it was almost a hundred percent successful in this city last month.

RPW: This matter of unity may or may not carry a price tag – of course one case to another. That is, that the – without the information about the boycott, say, in New York – except on this point. Gulamussen said that his schedule for integration was not kept he would rather see the school system wrecked. This is on record. That the school – public schools may have served their purpose anyway, he said. Now, this position, you see, - we'll say that brings in other questions – unity may be too high a price to pay for this – might be.

RG: I agree that unity would be too high a price to pay under the circumstances which you just related to me. I did not know that Gulamussen had made the statement –

RPW: He made it – yes.

RG: - that he would rather see the school system wrecked than not to maintain the schedule which he felt was satisfactory integration. I feel there is a point where you can reach where it's just not tenable.

RPW: But youth is not the only consideration.

RG: Oh, no. There must be unity with a purpose, and a worthwhile purpose. Now of course here in Cleveland we felt that the school boycott, a one day boycott, would serve a worthwhile purpose to dramatize to the entire community, to the nation, to the world, how our children are being treated in Cleveland. However, suppose this had been a decision to have a boycott for two months, then I dare say we would not have had the unity even in Cleveland with such a movement as a two-months school boycott.

R PW: The question of integration is not the only issue with you here, is it? It's quality as well.

RG: No, the real problem is quality education, and I feel that some people do not understand what we mean when we say quality education. I don't know whether you know it or not, but the Cleveland Board of Education as a result of the United Freedom Movement ' s presentation last fall, appointed a citizens' council on human relations to study the school system and to bring forth some recommendations to eradicate discrimination and various other things existing in the school system, to bring forth recommendations for an inter-service training program for teachers, to bring forth recommendations as to how we can bring about greater pupil contact between groups of different racial and ethnic backgrounds, to bring back recommendations as to how we can help the educationally deprived child, and then to bring back recommendations as to how we can effectively integrate the Cleveland school system, taking into consideration all the rights, privileges of every one in the city. This committee had sixteen members, five of which were Negroes – and I was appointed to this committee, even though I was active in the civil rights organization. I was the only Negro who was appointed to the committee who was active in civil rights organizations and the United Freedom Movement. The only other person appointed to the committee who had an axe to grind or who was affiliated with some other type movement was a young white fellow from the Collinwood area, which is an area where Negroes children are being bussed in as a result of overcrowded conditions in the Negro areas. Now, this committee met for a period of four months approximately from November 20th until March 31st. We found, for instance, that there were schools on the west side that were predominately white, or all white. In one instance there was one junior high school that only had one Negro child in the junior high school. But at this school for instance the pupil turnover between September of last year and January of this year was about a fifty percent turnover in pupils. Then we found that at this particular school there was no parent teachers association. The parents weren't interested enough to have a PTA. We found that there was a high absentee rate, a high tardyism rate. We found also that at this school the principal related that half of the children graduated from this junior high school were not ready to enter high school. Now, this was a school where there was only one Negro child – there were nine hundred white – or more white children there – there were only two Negro teachers in this school. So this is the type of quality education that they are getting on the west side. Now, another example of the quality of education we're getting here in Cleveland for all children is the fact that last week – week before last – they announced the winners of the National Merit Scholarship Examinations, and these examinations are given all over the country, and in greater Cleveland we had several scholarship winners. In the city of Cleveland, which has over 150,000 children in the school system, which is more than double the next largest community in this country, there was only one child to win a scholarship in Cleveland. Whether it's important or not, the one child was a Negro girl. Not one white child in Cleveland won a scholarship. Now, where we are now – I live here in Shaker Heights – this is a rather small suburb, and this is a suburb where there aren't too many children – not nearly as many as you have in Cleveland – but they had about two or three – I know at least two scholarship winners in this small suburb. In University Heights, another suburb just east of Cleveland, you had one or two or three scholarship winners in that small suburb. But in the city of Cleveland you only had one out of all the thousands of children in the city, to win a scholarship.

RPW: Yes, that makes the point.

RG: This to me speaks more clearly than anything I can say as to the quality of education all children are getting in the city of Cleveland. We do not have libraries in our elementary schools in Cleveland, and Congressman Green when she was here about two weeks ago deplored the fact that in a city of this size and magnitude they have no libraries in the elementary schools. This is ridiculous. So really as we complain about the integration we are also complaining about a lack of quality education in the community – in this community of Cleveland.

RPW: Do you have children?

RG: No, we have no children unfortunately, but I have clients who have children. I don't want to say that I am being selfish about this because I did come up through a segregated school system in Kansas, and I know the ills that can be derived from having a segregated education, I know how difficult it was. When I went to the University of Kansas, for the first time in my life – Lawrence, Kansas, I was thrown into contact with white students. I had been an honor roll student in Kansas City, Kansas, in the segregated school system. I was on the Honor Society, and I did not have to study too hard because all the Negroes in the community went to this one school, Sumner High School, and when I graduated from high school there were only about 160 children graduating. So you can see how limited my competition was. But when I was thrown into competition with children from all over the state of Kansas, all over this country, and foreign students from all over the world, for the first time in my life I learned that I had to study, and I had to work a little harder to keep up, and I never was able to make the honor society or honor roll in college because I did not have the background I felt I needed to compete on equal basis with these other children because they were taking courses in high school that we didn't even have in our high school. And this is what we are fighting for in Cleveland, and I know this, that if a child does not have a good education he cannot come out and get a good job.

RPW: Have you been following this HarYou program in Harlem, in the papers?

RG: Which program is that?

RPW: HarYou – H-a-r-Y-o-u: - the new –

RG: (talking together) … action for youth that's under the federal program for delinquent children?

RPW: Yes. Dr. Kenneth Clark is the mainspring of it.

RG: Yes, we have one here in Cleveland similar to the one in Harlem, called CAY in Cleveland – Community Action for Youth.

RPW: Has that been effective?

RG: Well, I hesitate to say. They've had a very difficult time getting it off the ground because of many petty jealousies existing at the top. We had the assistant director who resigned, he was the man that did all the leg work, to get the money for the program in Cleveland.

RPW: How much money was involved in it here?

RG: Let me see – I think it was about ten million dollars or something like that.

RPW: Pretty substantial.

RG: Yes, it's very substantial sum, and it's a temporary program. They have had a difficult time hiring staff – they're just getting the staff completed, because a lot of people are fearful of coming to this city for this temporary program – it's only guaranteed for three years, and I have several friends working in the program, and the work that they are doing is a very excellent job, but they've had difficulty getting it off the ground.

RPW; Well apparently the other has an enormous financial background – a couple of hundred million, apparently –

RG: In Harlem? We may have more than ten million dollars allocated to it, because I have not been active in the program and there are others who know much more about Community Action for Youth than I know about it.

RPW: What I was getting at is this –

RG: In fact, they just brought a boy from New York to head this one – a 36 year old Negro fellow, to head the program here.

RPW: What I was getting at was this, that Dr. Clark has in recent years changed his view that he had some years ago – not too many years ago – and some others who are responsible and thoughtful people in the New York system – the social New York system of schools – who are interested in it – have changed their position – modified it – not in saying – not integration but in saying that this is not – it has become secondary for the drive for immediate crash program education. Integration not as the watchword, integration to be achieved but immediately improve on the quality program.

RG: Creating the quality of education –

RPW: Immediately.

RG: I have heard that Dr. Clark has somewhat shifted positions on –

RPW: (talking together) He has shifted positions on that, and a lot of other people have too in the last year as far as I can make out.

Oscar Handlin had his recent book, and his desires and his prescriptions I think would satisfy most people. That is, he is for an integrated society and for integrated schools without any question – no equivocation – it's a question of how you arrive at this. He wants to emphasize equality as a means rather than integration as a solution – equality of means by all legal aspects and all – not merely civil rights but all the but integration has been a difficult thing to achieve in certain practical ways immediately, and he emphasized that the approach of the quality rather than the other.

RG: I agree that integration in itself should not be the total end, but in Cleveland for instance it will be very difficult to integrate all the children in the city of Cleveland. In fact, there are more Negro children in the city of Cleveland than there are white children in the school system.

RPW: There's our problem right there.

RG: So there's a problem, and not only that, but Cleveland is peculiarly set up physically in that we have a river running down between the east side and the west side of Cleveland, and most of the people living on the west side of Cleveland are white, and I understand that close to 85 or 90 percent of the Negro children live east of the river on the east side, so right there you have a somewhat more difficult physical barrier toward integration than in most cities. But on the other hand, we are not asking for hundred percent integration of the school system, we're not asking, for instance, to have children bussed across the city, a massive reverse bussing is what it's called. We're only asking to achieve maximum integration under the situation in Cleveland. But in addition to that we want to upgrade the quality of education. There aren't many areas where integration can be achieved, and we want them to do the things necessary to integrate.

RPW: Now, your situation, as far as I can make out, is somewhat distorted or given incomplete coverage in the national press.

RG: That's true. For instance –

RPW: As far as I can make out.

RG: Well, in the national press, but even in the local press, we don't get the proper coverage of the problem here in Cleveland. The local press does not paint a very good picture of the civil rights movement in Cleveland. At every opportunity they attempt to more or less miscolor the situation and to confuse the citizens. I have had many white citizens that I've talked to – many groups – and they ask why could not you have gotten this in the newspaper? Why could they not explain the situation the way you have explained it? And I indicated to them that we don't run the newspapers. We give them releases and we give them statements – they will not print them. So we really don't get a good dissemination of the facts not even in Cleveland, not just in the national press but even locally. So this is one of the great problems we have in this city. People just don't know. There are so many things that are wrong with the city of Cleveland 's educational system and other things going on here, that you just cannot get a favorable press. For example, the press – when I say the press I am speaking about both newspapers, since one of them is called The Press – the newspapers in Cleveland would lead the people to believe as a result of the Supreme Court of the United States not deciding to hear the Gary, Indiana case, that the Supreme Court of the United States has pronounced that the neighborhood school is the law of the land and they will do nothing to disturb the concept of the neighborhood school, and the United States Supreme Court said nothing of the kind. They only refused to hear the case. This does not make a conclusive finding that the neighborhood school is sacrosanct. Now, on the other hand we didn't read anything to my knowledge in the Cleveland papers about the Manhasset, New York, decision, where the federal court decreed that they should integrate the school system and that the board of education was within its rights to take affirmative steps to integrate the school system and eradicate de facto segregation. In the New York Times Tuesday of this week – Monday of this week, I guess – no, Tuesday – Tuesday of this week – day before yesterday – they had an article in the New York Times about the Supreme Court decision, and they went on to amplify what it meant and they had a statement in the New York Times attributed to Robert Carter, the teacher counsel of the NAACP, and then they also had an article about the Montclair, New Jersey, decision that was rendered by the Supreme Court of New Jersey, in which the Supreme Court of New Jersey unanimously decided that Montclair, New Jersey, school board was right in eradicating – completely eliminating an all-Negro junior high school and distributing the Negro children to the other three junior high schools in the city. There was nothing in the Cleveland papers about this decision – nothing.

RPW: This is the end of Tape #1 of the conversation with Mr. Gunn. Proceed on Tape #2.

(end of tape)

CollapseTAPE 2 Searchable Text

Collapse[These digitized texts are based upon 1964 typed transcripts of Robert Penn Warren’s original interviews. Errors in the original transcripts have not been corrected. To ensure accuracy, researchers should consult the audio recordings available on this site. Time stamps are included in the retyped transcripts to aid in this process.]

ROBERT PENN WARREN RICHARD GUNN TAPE #2

[00:00:01] RPW: This is tape #2 of the conversation with Mr. Richard Gunn – proceed. Are you aware that – division of impulse – or does it mean anything to you?

RG: Yes, unfortunately I am aware of the impulse you have just referred to, but there are some Negroes who attempt to lose their identity with the Negro community, and as they become more affluent they seem to have less identity with the Negro community, and in many instances this is manifested in the fact that they may leave a particular church affiliation with a Negro church or a predominately Negro church and go to a predominantly white church. In many instances they may try to associate with others of different racial backgrounds and racial identifications. And they will not in many instances identify with the so-called Negro civil rights movement for various reasons, and they tend to feel that possibly since they live in a nice neighborhood and they have a good job and they enjoy the privileges of first class citizenship, they feel, that they cannot readily identify with the Negro cause per se. I am painfully aware of this, but I feel that recently here in Cleveland we have found a rallying point, and many of these people have realigned themselves with civil rights organizations in the city. I am aware of this problem.

[00:01:59] RPW: A significant shift has taken place you feel here?

RG: Yes, I feel that there has been a significant shift. I don't know whether it is a permanent shift, but I have seen some of my friends – I alluded to the fact earlier that we had a meeting of twenty-five or thirty Negro leaders, and many of these people in this particular meeting I'm sure are of the opinion and the feeling that you just mentioned, that they have somewhat lost their identity, and I can say that there was not complete unanimity in conversation, but there was complete unanimity when a decision was finally called for. I know that there are those who feel this way, and there are those Negroes who do not want to antagonize their dear white friends. But when the chips were down they had to take a stand, and I feel that many of them did not want to be called Uncle Toms, and this had already been –

[00:03:09] RPW: The pressure is on.

RG: - this had been bandied about – this is what was being said. When the meeting was first announced in the newspapers it as leaked by some one in the newspapers and Negroes immediately started saying that these were just a bunch of Uncle Toms being called to this meeting, they did not know – for instance, many people I talked to that I had been invited, and that several other fellows who had been active in the civil rights movement had been invited.

[00:03:36] RPW: Isn't that part of a tradition almost – a traditional feeling among Negroes to assume that success in ordinary standards – success means that a Negro who has succeeded has moved out into the white world and cut his – potentially cut his ties – isn't that a fairly common feeling among the masses of Negroes?

RG: It may be. I cannot always speak for the masses, but you see here where I live, and I don't think that there has been any undercurrent of criticism against me for my participation. I don't know whether most Negroes even know where I live. But certainly they do not feel that – maybe because I have reached a certain position – that I will sell them down the proverbial river, or that I am an Uncle Tom because I'm not, and I've been very forceful in this civil rights movement here in Cleveland.

[00:04:33] RPW: I know you have – that's not the point at stake. It's a question of whether there's a split between the mass of Negroes – the really deprived mass – and the possibly enlarging group of Negroes with considerable or great success. Do you think that's –

RG: I don't think so. I think that there is not the obvious split because we call can identify when there is a reason for identifying. We all identify together regardless of our status, because as I have often remarked to my white friends, no matter how high I may rise, no matter where I may move, no matter how much money I may have or may make, I am still a Negro, and the lowest grade of white man will look at me and feel that he's better than I am, though he may not have as much money as I have, though he may not live in a house comparable to mine, but he feels he's better than I am.

[00:05:37] RPW: One analysis of this new Negro movement is that it's primarily a sort of middle upper class movement, that is, the successful or more or less successful Negroes who have of success as you described it. But that has been the cutting edge providing the leadership group. Professional people, by and large, and teachers.

RG: I think that you may have a correct analysis there, that the leadership in the civil rights movement here in Cleveland basically is comprised of people who are those who have the ability, they have the education, possibly have attained a ceratin status in the community, and they are providing leadership. I think the real difference is this, that in the past Negroes who have attained the status you refer to, have not wanted to serve in the leadership role to the extent of causing discomfiture in the majority community.

[00:06:56] RPW: And now they'll take the risk?

RG: Well, there are some who are willing to take the risk, and I think that basically they're the younger fellows who are willing to take this risk. In the past many of your so-called Negro leaders have been rewarded for their attainment of success by being given jobs with the government or with governmental agencies within the city – appointments to boards and agencies where they can draw a salary – and naturally when you're in this position you don't want to rock the boat too much for fear of disturbing the source of income, whereas here in Cleveland today those individuals who are taking part in the civil rights movement, basically are those who have no responsibility to governmental agencies. They are those who have jobs where they can work in civil rights or they are in their own profession, and they have nothing that they can necessarily lose that is given to them by the white community.

[00:08:00] RPW: They're not living on patronage of any kind.

RG: That's right. And as a result they feel much freer to serve as leaders in the civil rights movement in Cleveland.

[00:08:10] RPW: Let me cut to something else, Mr. Gunn. Going back to the matters of demonstrations, now some Negroes, some of, you know, importance and authority, would say there are two types of demonstration – legitimate demonstration and illegitimate – put it this way – use those words loosely. One being – the first being a demonstration directed at a particular target, you see. Now, a distinction would occur for some people in the sit-ins, the stall-ins – they're legitimate – the fair grounds demonstrations as legitimate, having a special target, and not being antisocial - particular point. Does this distinction make any sense to you as a lawyer?

RG: Yes, I think that really what we have tried to do in Cleveland, though some people disagree with this has been our technique, we have tried to relate our demonstrations to something fundamental, something real.

[00:09:18] RPW: A specific target.

RG: Some specific target, rather than going off on a tangent and stopping traffic on Lake Shore Boulevard, for instance, because of discrimination in the schools. We try to relate it to a specific problem. Now, there are those who feel that this was not done in the case of certain schools. We first started demonstrating as far as the educational problem is concerned, around the board of education last fall. We had two or three hundred pickets walking around the entire block where the board of education is situated. And then this past winter in January when it was rather cold, we had pickets around the board of education. This did not seem to help, so we were picketing because of the segregation of bus transported children. Negro children were being segregated in the receiving schools where they were being transported. So after picketing the board of education, then we shifted our focus from the board of education out to the receiving schools where the Negro children were located. And this was the first time that we had violence in Cleveland as far as demonstrations were concerned. Our pickets were peaceful. I want to stress that. Our pickets were peaceful demonstrators, they marked with dignity, with a purpose, and they were not violent. But the white neighbors living in this neighborhood where we went, they spat upon our pickets, they pushed them, they shoved them, they drove automobiles up on the sidewalks, the curb, and almost struck our pickets.

[00:11:04] RPW: Is this the Italian section?

RG: No, this was not the – well, there are Italians living out in this section too. This was out at Brett and Memorial School. Now, there were police there, and the police made no arrests even though there were indications and the police saw these various assaults taking place. Then a few days after this demonstration we proceeded to decide to demonstrate at Murray Hill School – this was another receiving school – and this is an Italian neighborhood – just about all Italians. We did not even reach the site of this school because the people were so belligerent and antagonistic. As we gathered at a parking lot down near Western Reserve University, preparing to march up to Murray Hill School, we received word that there were a lot of people gathered around this school. They were very belligerent, and we were told that there probably would be bloodshed, possibly death, if we walked up there. There were police there, and unfortunately these police did not protect the innocent victims who were up in that neighborhood because there were Negroes who accidentally drove through the neighborhood, not affiliated with the civil rights movement, whose cars were stoned and who were – well, some of them were struck – two Negro reporters were chased, white reporters' cameras were smashed – one white reporter was up on the third floor taking pictures – the second floor – and they threatened to throw him off the porch if he did not surrender his film. And this was the type of conduct that we had up at this school. Negroes had fruit and vegetables thrown at them. One of my very close friends and a member of my church, a lawyer, he had to seek refuge to protect himself because he came up to picket not knowing that we had decided not to picket. And this was generally a chaotic situation there. Police actually saw the law being violated but they made no arrests. No arrests were made. And this gives you an idea to what some people felt was wrong. They said they were up there to protect their children. Why, all these demonstrations were peaceful so there was no reason to protect their children, and particularly to protect their children with violence. We arranged these demonstrations so they would occur when the children were in class, and not when they were coming to school or leaving school. We specifically did this so the children would not see the demonstrators. And they all stated that we made children the pawns of this situation, that the children would be disturbed by this. Well, the children should not have seen it because they were in school. Now, many people said that this was a wrong place to demonstrate because the board of education headquarters were where the decision was made.

[00:13:59] RPW: Who said it was wrong to demonstrate?

RG: Well, the newspapers said it was wrong to demonstrate out at these school sites, and many white citizens said we were wrong for doing this. Now, I feel that this does not a situation that it's illegal demonstration or unlawful demonstration, as it related to something that was going on in those schools.

[00:14:21] RPW: You had a clear target?

RG: That's right. We had a clear target right in the schools where we were demonstrating.

[00:14:26] RPW: How did you feel about the stall-ins as compared with the actual demonstrations in the fairgrounds, picking particular pavilions – does that distinction apply there?

RG: I think there's a distinction, but really I'm not one of the persons who are way out on the demonstration question. But sometimes I feel that these things are necessary.

[00:14:49] RPW: Which things are we talking about now?

RG: The stall-ins. Now, maybe I would not participate in the stall-ins, but I would have no objection to others doing this if they thought this was necessary in their community. Evidently there were not many people who agreed with the fellow from Brooklyn because it was not effective. But really, if they feel this was necessary in some locality I would have no objection to it.

[00:15:14] RPW: There is a – clearly there was a big split of opinion on the stall-ins. That is, people who were perfectly willing to demonstrate in the fairgrounds or at particular targets and go to jail for it, would not condone the stall-ins, as we know from the fact of the whole debate between the central office of CORE and the Brooklyn and the New York –

RG: All I can say is this, if you're willing to go to jail, does it make much difference for what reason you're going to jail?

[00:15:46] RPW: Well, the question would be this – what is your relation to society, not because of jail but because of the thing you did.

RG: Well, to my mind, when you're doing something to subject yourself to arrest, it's wrong regardless of whether it's killing some man or whether it's stabbing a man and injuring him or shooting someone and injuring him – this is wrong. Now, one is worse than the other, of course. A murder or homicide is worse than maybe stealing a nickel candybar. But they're both wrong, and I would hate to – they're legal – I would hate to stealing a candybar with murder or homicide. But if you're going to do something – commit an offense that is comparable in severity of punishment, I can see no difference between stalling in on the highway or causing a disturbance inside the fairgrounds. If you have committed yourself to this type of law violation I see nothing wrong with it. Maybe this would shake the people up in New York a little bit. Maybe it would have been a good thing if three thousand Negroes had stalled their automobiles on the highways leading to the fairgrounds. Maybe this would have dramatized to the city of New York and to this entire country that Negroes are dissatisfied with their lot. And I hesitate to even reach this point, because I am fundamentally a lawyer first, and I'm in favor of maintaining the law at all times, but it disturbs me in this country of mine that we must do the many things we do to gain just the smallest measure of success as far as our requests for rights are concerned. I often say that my wife and I went to Europe last summer, and we traveled throughout Europe – not all over Europe but we went to ten countries. At no time was I aware of any discrimination in Europe. I'm not a citizen of Europe. I'm a citizen of the United States, and I traveled all over Europe and stayed in hotels, I ate in restaurants without question all over Europe – the parts that I was in. But in my own country several years ago my wife and I drove to Seattle and we took a plane and flew up to Alaska, stayed there several weeks and then came back down to Seattle, drove to California, then came back through the southern part of the United States, through the southwest part, and when we reached New Mexico, we were refused accommodations at a motel, in New Mexico. Now, I know this happens in our country because I have been aware of this for many, many years, having lived in Kansas City where a Negro could not even go to a white hotel when I was living there. It's different now. But you wonder what do you have to do in this country to be accorded full citizenship rights when the Constitution is existent, the Bill of Rights is existent, when we profess to be a democracy, when we profess to be basically a Christian national. What do you have to do to shock the consciences of the people in this country in order that they will treat me as a human being, in order that they will give me all the rights that anyone else is entitled to? When I can go to Europe and have no trouble at all, but I couldn't go to Mississippi and have the same feeling and treatment that I had in Europe.

[00:19:26] RPW: Mr. Ellis – Charles Ellis, told me two or three months ago now, that he had much more hope of settlement in Mississippi than he had down farther south.

RG: I think he's right. You know, this is a great problem, and I think this is what is bothering people in Cleveland and throughout the north. You know, it was so easy for the northern newspapers, for the northern white people, to criticize Mississippi in the case of the young man – Meredith – trying to go to the University of Mississippi, and criticizing Alabama when the governor of Alabama was trying to keep Negroes out of the university, and criticizing the governor of Arkansas when he tried to keep these little girls out of the high school in Little Rock, and we all said in the north that this was horrible, the way they treat Negroes in the south and the many things that they do that are inimical to the safety and welfare of Negroes, and when they looked in the papers and – in the south and saw the pictures of a Negro girl on the ground and a policeman – a white policeman with his knee in her collar down in Birmingham – the white citizens of the north felt that this was horrible and they deplored what the people in the south were doing. And they just felt that the people in the south should change. Now, when the same thing reaches the north, now many of the northern whites are saying, now, the Negro should be patient, and you can't achieve all your rights over night. It was easy for them to criticize the south and say it's wrong for the white people to treat the Negro the way they do in the south. But when the same thing comes up in their own back yard – their front yard, and we find that many of the northern white people have the same feeling of hatred and the same feeling toward Negroes that have been sublimated all these years that the southern white man have – the northern whites hate to see this come to fore, and in many instances, as you suggest, it will probably be more difficult for us to obtain our rights in the north than it will be in the south.

[00:21:44] RPW: One of the arguments runs, in the south it's clearcut situations, it's by and large a matter of local ordinances and state laws as well as local practices. The target is clear. The target here is not clear in the north.

RG: Well, there are many whites here in Cleveland, for instance – I've talked to some – they feel that the Civil Rights Bill is wrong. I had some young people – I spoke to a young group over on the west side, a suburb on the west side, and they felt that it was wrong for the United States Government to dictate to a businessman whom he should serve in his business. And one young fellow asked me why is it that the Negroes wanted to eat in white restaurants anyhow – why didn't they eat in Negro restaurants and stay with their own people? And of course I asked him, what would he do if someone suggested that – I don't know what his nationality was, but if he was a German, that he should eat in a German restaurant, and he would forever be forbidden to go to a Chinese restaurant and have Chinese food, or a Hungarian restaurant and have Hungarian food, or to any other type of nationality restaurant and eat. This is a misconception that many northern whites have, that the civil rights bill pending before the Senate today is detracting from the rights of the white businessman and is going to hurt the white community. They don't realize that in the state of Ohio today we have just about all the laws on the books that are incorporated in the civil rights bill. We have a fair employment law in the state of Ohio. We have a law pertaining to nondiscriminatory practices and places of public accommodation, we have a public accommodation law. We have laws that protect the voting rights of Negroes in this state.

[00:23:43] RPW: Housing?

RG: We do not have a fair housing law, but the federal legislation does not have any provision for fair housing. So this – we get repercussions from the white community in the north as to the civil rights bill, when really the civil rights bill will not even have any application to most northern states because we already have the laws. This law is directed primarily to the south, where Negroes do not have the right to go into a place of public accommodation because there are so many laws in states and cities preventing this. And Negroes do not have the right to vote, particularly in Mississippi and some other states. So this is going to bring those rights to those people the same as we have in Ohio. But you get this backlash of criticism from whites communities here in the north against the civil rights bill.

[00:24:35] RPW: According to the last poll results I saw, we have about seventy percent northerners favoring the accommodation section of the civil rights bill, but about sixty-five percent saying they'd move out – considering moving out if in their section Negroes moved in. That's a strange paradox. Accepting public accommodations but resenting apartment house or subdivision or –

RG: Well, you know this is a funny – this is a paradox, Mr. Warren, that in the south – you know they often say this – we Negroes allude to this fact – in the south the whites don't care where you live, they don't care if you live next door to them. I mean, there are many places in the south where whites and Negroes are living in the same neighborhood. But they don't want you to go to school with their children necessarily, and they don't care – they don't want you to rise above them too much – they don't object to it but they don't want you going to school with their children. They don't care how high up you go in the south, they don't care whether you live in their neighborhood, but they don't want you to go to school with their children necessarily, or mix socially with them, and go to places where they go socially. In the north, the whites in the north don't care how high you go, they don't care how much education you get, they don't mind you coming into the restaurants sitting at the next table to them, but they do not want you living in their neighborhood.

[00:26:13] RPW: That's the point.

RG: This is the thing. They will accept anything but a Negro moving next door to them. Whereas in the south they will accept your living next door to them, but they don't want you to go into any of their places of public accommodation or going to school with their children. This is an interesting paradox in this country.

[00:26:32] RPW: It is. Part of that is historical accident of course. That is, a person in association with Negroes is no rarity in the south. It's quite common.

RG: But it isn't so common in the north. I've been surprised – I've been on television several times recently and radio, and as a result of these appearances you get people calling you, and it's surprising the number of whites who call and – eventually I usually ask them whether – they're not prejudiced – they always start off their conversation by saying they're not prejudiced – and I always like to dispel their feeling of non-prejudice by asking them whether they would like to have a Negro to move next door to them, and invariably they just will not accept a Negro living next door to them, and if – finally one lady said that she wouldn't mind my living next door to them because she thought I was a fairly nice person after talking to me on the phone – but they generally – she said I don't mind you living next door to me, Mr. Gunn, but I wouldn't want a Negro living on the other side of me. And this is interesting, that many of these people don't even know Negroes. They have no contact with Negroes. They have not the slightest conception of how we live. They have not the slightest conception that we have the same desires for nice neighborhoods and nice homes that they have, and we maintain our homes and our neighborhoods when we can afford to maintain them. And it's interesting that they just don't understand. I think that we've had one project in Cleveland that has helped dispel many of these fears. We’ve had a series of interracial discussion groups called dialogues, wherein Negroes and whites meet in each other's homes and they discuss problems concerning race relations and things of this nature. It's just an attempt to get people together to discuss the problems in the racial field. And it has met with fairly good results in this city, and many associations have been made that are more or less ongoing.

[00:28:40] RPW: Do you think it's actually bona fide things – that sort of association – that sort of –

RG: Well, it has its inception in the false type of presentation, in that the people are brought together artificially. But as a result of this there have been some continuation of these associations, and I think the greatest test is when a white person who meets a Negro will eventually or ultimately invite the Negro couple or two Negro couples in to his home on a social basis where he has invited his other white friends who may not have had this exposure. And I think this is the real test of how effective the association has been. And there have been many instances of this being done. I know my wife and I went to one person's home – couple's home one night where they had out of town guests from another city, and they invited several of their friends in and they had two Negro couples there. And the evening – we spent the whole evening. There was nothing said about the racial problem, and I'm sure this is a real test, but I'm quite sure that many of their friends were somewhat disturbed or concerned about it. There have been instances – I spoke to a group last Sunday out in Willoughby, Ohio. This is out here near the lake, a suburb east of Cleveland, and this lady had several white couples in and two or three Negro couples and I went out to talk to them. And she said before she invited the group her next door neighbor came over and talked to her for two hours and just told her off, told her how wrong she thought she was for inviting Negroes out in their neighborhood and just gave her the devil generally. And she took it and told her neighbor that she thought her neighbor was wrong. But this is the type of abuse that whites have to take when they invite Negroes out into their homes. There was one young lady there last Sunday who indicated she lived on the west side of Cleveland in the suburbs and she would not dare invite any Negroes to her home for fear of recriminations from her neighbors. But I say that when a person feels that he is not free to invite someone of a different race to his home, this is partially slavery too. I mean, you're not free to do what you would like to do. And this is true of many whites in the south. A lady called me last week. Her son was just sentenced to one year in prison down in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

[00:31:31] RPW: He was a demonstrator there?

RG: Yes, he left college to work in this movement. He's from Cleveland. And she went on to say that her son espoused this proposition, that he feels that he is not free when there is a south –

[00:31:46] RPW: Is he a Negro or a white?

RG: He's white. He lives in one of the suburbs here. And he feels that he is not free when he cannot even go to a Negro restaurant to eat with his Negro friends without fear of being arrested. And now he is in jail. He was sentence to one year at the farm – or labor farm or something. And they suspended two years with the further condition that he not participate in civil rights demonstrations for five years. This is a young white boy.

[00:32:21] RPW: As long as he says in North Carolina.

RG: That's right. But this is actually what has happened down in the city – he was going to school in Chapel Hill. I don't know – it's surprising to me that this young man was caught up in this movement because he lives in a suburb in Cleveland where there are no Negroes living in this particular suburb, so that I imagine his exposure to Negroes has been very limited.

[00:32:47] RPW: It sounds so. Very limited. There's a good deal of resistance – how much I don't know because you can't assess these things - - it's always hearsay to me –

(end of tape)

Collapse