Warren begins with an anonymous quotation about integration and the “destruction” of the public school system. The two discuss the timetable for school integration, and Wilkins argues that quality of education is key for African American students. He suggests the importance of instilling racial pride and an African American history. Wilkins discusses W.E.B. DuBois's theory of African American's "double consciousness." Wilkins and Warren discuss how integration will change the South and southerners, and they consider whether integration will differ by region. Warren prompts Wilkins to discuss Gunnar Myrdal’s thesis about Reconstruction.

Notes:

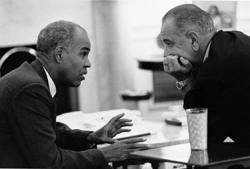

Image of Wilkins and President Lyndon B. Johnson: Library of Congress.

Image: Original caption: Roy Wilkins, a civil rights leader and director of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, sits in a chair in the NAACP office. New York, New York. 1963. Copyright: Corbis.

Audio Note: Audio on tape 3 cuts off a few paragraphs short, but the transcript is complete.

Audio courtesy of the University of Kentucky.

Roy Wilkins

Roy Wilkins (1901-1981) was a journalist, editor, and civil rights activist. Born in St. Louis, Missouri, he attended the University of Minnesota and graduated with a BA in sociology in 1923. His career as a journalist began with the Minnesota Daily, and he later worked for African American newspapers such as the St. Paul Appeal and the Kansas City Call. In 1934 Wilkins replaced W.E.B DuBois as the editor of The Crisis. He helped organize the 1963 March on Washington, and he participated in the Selma to Montgomery marches as well as the March Against Fear in 1966. Wilkins was a proponent for nonviolence and opposed the militant approach of the “black power” movement.

Image: Original caption: Roy Wilkins, a civil rights leader and director of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People from, sits in a chair in the NAACP office. New York, New York. 1963. Copyright: Corbis.

Transcript

TAPE 1 Searchable Text

Collapse[These digitized texts are based upon 1964 typed transcripts of Robert Penn Warren’s original interviews. Errors in the original transcripts have not been corrected. To ensure accuracy, researchers should consult the audio recordings available on this site.]

ROBERT PENN WARREN – MR. ROY WILKINS Tape 1 April 7, 1964

[00:00:10] Warren: This is tape one of a conversation with Mr. Roy Wilkins, April 7th. Back on – I guess we’re going now. I’ll use some of these guides, but please head off anywhere or any time you feel inclined. May I start with a quotation of Mr. Galamison of a few weeks ago, for a response? This is a TV interview, which I picked up from the press. “I would rather see it, the public school system, destroyed” – than not conform to his time table of integration – and, I’m quoting again, “maybe it has run its course anyway – the public school system.”

Wilkins: I recall this.

[00:01:01] Warren: You recall that?

Wilkins: I recall this, Mr. Warren, and I must disagree absolutely with every syllable of it. I cannot imagine that anyone soberly would want to contribute to the destruction of the public school system, because it did not conform completely to his image of it, or his desire of what it should be, or – and this is the most fantastic of all – to the timetable that he had set for its revision. Now – I know the Reverend Mr. Galamison, and he was at one time the President of the N.A.A.C.P. chapter in Brooklyn, New York. He’s the minister of a successful congregation – or, I should say, he’s a successful minister of a good, Presbyterian congregation – the Siloam {Presbyterian Church. I have respect for Reverend Galamison’s devotion to this cause, for his single attention to the public school system of the City of New York and especially of the Borough of Brooklyn. He knows a very great deal about it and about its deprivations of Negro children, but I cannot imagine a man saying that he would destroy a system and that perhaps it had run its course – just because it did not conform to a revision as scheduled, set up by the Reverend Dr. Galamison, and I would say the same thing if a man in Pittsburgh said this, or a man in Omaha, or a man in Meridian, Mississippi. We Negroes want the improvements in the public school system – and among them, of course, the elimination of segregation, based upon race – the institution of the same quality education in the schools attended by our children as those attended by other children, and we want Negro teachers and we want Negro supervisors, and we want all the opportunity, but the only way our form of government and our structure of society can survive is by some common indoctrination of our citizenry, and we have found this in the public school system. And, for any reformer, black or white, zealot or not, to come along and say, “I’ll destroy it, if it doesn’t do like I want it to do”, is very dangerous business, as far as I’m concerned.

[00:03:52] Warren: Here’s a line of speculation now, which I’d like to refer to here in terms of integrated schools. There are situations where it becomes more and more difficult to implement the idea – no matter what the good will is – let us say, Washington, D.C. ten years from now, when the City becomes almost entirely a Negro city. How can integration as an objective, you see, of the school system be achieved in those circumstances? Or can it be?

Wilkins: I think this is a very real question, and it applies not only to Washington, D.C. and what it might be ten years from now, but it applies, for example, to the Borough of Manhattan, a very steady trend toward Negro and Puerto Rican enrollment increase, and a decrease in the so-called white enrollment in the Manhattan Borough. I think the question of whether you can achieve what is now popularly called integration under such circumstances or not, is a very real question – and I don’t know but that we then may be faced with the question that we ought now to be facing along with the question of integration – and that is the quality of public education.* I don’t think white people would assert that schools attended only by white people were inferior schools, with respect to the quality of education – mathematics, history, social science, chemistry and so forth. They might well admit, as we maintain on our side, that their schools could be better schools if they had a diversity of enrollment and different racial strains in that school, and that these children would amplify their education by learning to live together and know –

[00:06:24] Warren: Let’s grant that –

Wilkins: That’s right, that’s right.

[00:06:28] Warren: Let’s grant that. I’m not – that’s not the point I’m raising, you see.

Wilkins: That’s right. But the – when you say that you can only achieve

* “integration vs equality” handwritten in margin

quality education through integration, then it seems to me you go a long way toward admitting that a school composed of your own racial group from top to bottom under the most favorable circumstances could not be a superior school. Personally, I’m not willing to admit that.

[00:07:03] Warren: Someone with whom I was talking about this – some weeks ago – said, “Take Washington. If necessary, we will have to go out to Virginia and bus them in” – them being white pupils – this being an absolute necessity in this person’s view of a school system – ignoring all the legal and other problems.

Wilkins: Yes, and also ignoring the welfare of the children. Now, you will find, if you have investigated this matter very extensively, you will find Negro parents who also object to busing their children – small children – great distances. Every parent does this. Now I hope nothing will be understood here to mean that I discourage the desegregation of the schools and all of the evils that have gone with desegregation. This must be a prime objective of the Negro community, and we in the N.A.A.C.P. intend to work at it consistently and persistently. But I think we ought to come to grips with the idea that a school in the midst of a black district, which isn’t going to melt soon, no matter how much progress you make in housing and chipping off the peripheries of so-called Negro districts, that a school in the midst of such a black ghetto has to be made a good school – so good in fact, that maybe pupils in other areas will want to transfer to it. It must have good teachers. It must have a top-grade curriculum, adapted to the needs of the people in the district, and it must have all the latest educational gimmicks to make it a good school, and it must offer incentives and it must give its graduates a horizon and all this sort of thing that a good school does.* Now, when we say that this can never be achieved unless the pupils in that school consist of more than one race, we make this as an absolute condition – then I think we’re on the way to not achieving what we want to achieve. The reason Negroes made a drive for integrated schools was because it was demonstrably clear that the best education was over there where the white people are – and the bad education is over here where the black people are. Therefore, if we want to get the best education – we’ve tried every other way – there’s nothing for us to do, but to go over there where they are.

[00:10:10] Warren: The tactical aspect of this, then should take precedence over some reading of integration as a – as an ultimate goal – and I’m referring now to the school system as such when it isn’t possible to integrate at the practical level.

Wilkins: Yes, I think we have to meet those problems when they come and we have to meet them with practicality and with good sense – with never any retreat on the idea of equality of opportunity for the races and the absence of racial compulsion, and direction – which is involved in segregation, and the

* “C Houdlin” handwritten in margin

inferiority that creeps into it, a segregated set-up, no matter how hard you may try. Look, witness the Northern school cities. Take a city like Cleveland, which has been thought for many years to be ideal. Take a city like Buffalo, or Boston, or Philadelphia, or Pittsburgh, or Indianapolis, or Detroit. Here you have systems, and some of their administrators swear and be damned that they’re not segregated – that they’re not unequal. “Well, “they say, “they may be unequal, but they’re not segregated. It was the housing people that segregated it.” But little by little, the administration of those schools has gone down; the downtown central authority has slighted them when it came to assignment of teachers. It put substitute teachers out there. It put new teachers out there. It gave the old teachers the favorable suburban or high-class residential areas where the children are presumably easier to teach because of their home backgrounds. It cut them on curriculum, and where they assign books, gave them not such good books, and so – even supervision and the tests and all the other things were slighted, and so segregation and inferiority did creep in. This is a very complex question.

[00:12:17] Warren: That’s inevitable, isn’t it? The past – it seemed inevitable in the past, which –

Wilkins: Well, I’m telling you – I tell you, you know, of course, that this has been a problem with educators for a long time, even when there were no colored children involved. The question of how do we equalize, or move toward equality of the education in the lower socio-economic levels of our cities?

[00:12:43] Warren: The class issue overlaps the – confuses the race issue of this kind, doesn’t it?

Wilkins: Exactly. Take a city that didn’t have – that doesn’t have any Negroes in it. It still has a school problem – a problem of how to provide the poor youngster with the same kind of education that the middle-class and upper-class youngster gets. And, the teachers in this school system dodge the schools in the poor districts, even though they’re poor white districts, because they say they come from homes where they don’t have books, where the parents didn’t go to college and where this – and it’s hard to talk to them – they don’t have the same vocabulary – the words don’t mean the same – and they can’t read as fast. I’d rather go to a middle-class home, where they subscribe to news magazines and picture magazines, and they go to museums and they go to the opera and they use their library cards, and it’s easier to communicate with those kids.

[00:13:37] Warren: May we test this now to see if we’re doing all right? You remember, no doubt, the article by Norman Padorits [Podhoretz] in Commentary a little time back?

Wilkins: I do, yes.

[00:13:49] Warren: I won’t read the quote then, about assimilation being the only – racial assimilation being the only solution to the Negro question in America. How do you respond to that, Mr. Wilkins?

Wilkins: I don’t know. I don’t know that I can put it into words. I’ve had the feeling that the author was trying to be daring in his analysis of the problem. I got the feeling that he was trying to say the unsayable. I don’t know. I couldn’t help but think of whether he could be found among those who might maintain that the Jewish-Gentile relationship will never be solved except by assimilation. I don’t think he is in that school. I don’t know how far assimilation will go in this question, or how much it is inevitable. I can’t see a thousand years ahead, or two thousand years ahead. I think there are some segregationists who claim they can see two thousand years ahead, and they say that this is not what we want here in 1964 – we don’t want this to happen in 5064, or something like that.

[00:15:32] Warren: There are some who would what they want too – not segregationists, but white people I know, who say – “Any price to be rid of the problem.” That’s almost – that’s between the lines of this article, isn’t it?

Wilkins: Exactly. Now, I think, of course, that there will, as the Negro’s economic and cultural position improves – and by cultural, I mean his adjustment to what the lords of culture of our day say is the culture. I don’t mean by that that his culture is necessarily inferior, but as he adjusts – as he becomes more like the people, and as he wins some economic advances – I look for more and more mixture between the races. I don’t ever look for it to take on substantial proportions. I think the Negro is very proud of himself. I think he has been proud in a sort of defensive way for many years. I think he is now proud affirmatively. He’s proud of being black. He’s found that black people are not what his white people told him they were and he, thus, will find no ready reason for escaping into the white race via marriage, or passing, or any other subterfuge.

[00:17:11] Warren: There’s – that is the notion of escape has become less and less important, is that the idea?

Wilkins: Exactly so.

[00:17:18] Warren: And with the sense of identity as Negro is more and more important –

Wilkins: More and more important – and as the economic barriers are removed. A great deal of the passing, you know, that was done by light-skinned Negroes was done for two great reasons. One was to avoid the humiliation that automatically went with the brown or black skin – the personal humiliation, and the other was to secure economic advancement.

[00:17:46] Warren: To get a job.

Wilkins: To get the jobs that you couldn’t get otherwise. Now, when you walk into a downtown store, and you see the clerk, who is a Negro, or a buyer in a department store who is a Negro, or a treasurer, or a cashier, where once you had to be light-skinned and conceal your Negro background in order to aspire to such a job, it thus becomes unnecessary to pass. And, this cause has been removed. Now, it hasn’t been completely and entirely removed. I don’t mean that – but I mean, it’s nowhere near what it was fifty years ago, or forty years ago.

[00:18:31] Warren: Say, five years.

Wilkins: Indeed so.

[00:18:35] Warren: On that point, DuBoise [Du Bois] long ago wrote more than once about the split in the Negro psyche as he understood it – the pull toward the African tradition, whatever that could be said to be, or toward the Negro and Negro culture, even one thought of as deriving from Africa, or one as developed in America. All of this, that pride in Negroness, as opposed to the other pull, the other direction, where the Negro can move into the orbit of Western European, American culture, even to the point of losing his racial and cultural identity, these being the two poles of the split that pulled him apart. Or – does that problem present itself to you as a real one, as something you observe among Negroes and/or something you feel?

Wilkins: DuBoise, [Du Bois] I think, was talking in a time and in a day when there might have been, among his class – and I stress this – some pulling and tugging. I don’t know. I can say only that in my own generation coming up, the Negroes who were born since 1900, and who live outside the areas of greatest racial tension and conflict, they –

[00:20:38] Warren: You get outside of the - yes.

Wilkins: Outside of that area. They, I think, have no discernible pull toward any African culture. They were Americans. They knew they were excluded from many areas of American life and opportunity, but they never thought of themselves as anything else, except disadvantaged Americans. Now, DuBoise [Du Bois] himself led the American Negro toward, and directed his attention toward his African heritage. In fact, he was a lone voice, crying in the wilderness for many years – Ethiopia, Pan-Africanism, and the Pan-African congresses that he started – the essays and articles he carried in the Crisis Magazine – the encouragement that he gave to Negro artists, and the sculpture – the beauty that he pointed out in African culture and African history. He did all these things himself and created in a rather reluctant American Negro – in fact, the Negro was so Americanized, that he adopted the white American’s view of Africa, and if you ask a Negro whether he was in Georgia, or whether he was in Michigan, the upper Michigan peninsula, about Africa, he would talk about savages and elephants and snakes and lions and that sort of thing. Not so today. Not so today. You find the American Negroes have very great pride in Africa, and they have been to Africa. They have travelled there – and they have met Africans here, many more than just the students who came before. They knew – I knew, for example, the Governor –General of Nigeria, when he was here as a college student, and I knew the President of Ghana, Nkrumah, when he was here as a college student. I knew the man who is now dead – the President of the African National Congress, who, when he was a student at the College of Agriculture at the University of Minnesota, back in the 1920’s, so that we knew Africans and we knew that they were not savages, and we knew that they had a history. And this latest – these last five or ten years in which the Congo has been dramatized and the difference between the British colonies and French colonies and Belgian colonies, and now the Portuguese Angola – this has all driven the Negro to very great pride in Africa. I don’t think there’s any ambivalence here. He wants to be a good American, but he’s by no means ashamed of Africa. He’s very proud of it.

[00:23:33] Warren: You remember Richard Wright, reporting his visit to Africa?

Wilkins: I don’t believe I read that report, no.

[00:23:43] Warren: It’s a very strange report. I had it here somewhere. I won’t bother to hunt it now. The substance is this – that he found that he couldn’t communicate – going there with one attitude and finding it impossible to communicate or even sympathize with, as he – the Africans he met even, you see, ordinarily. Drove him back on – within himself, some – a deep problem of communication.

Wilkins: I recall a discussion of this, yes. I recall a discussion of this. I think the American Negroes and the Africans are now in a period when they are discovering each other. I think some of the romanticism has probably rubbed off, and I think more genuine estimations are taking the place of this romantic attachment.

[00:24:37] Warren: They honeymoon is over then?

Wilkins: Yes, the honeymoon is over, and they’re analyzing American Negroes as people, and I think we’re analyzing Africans as people – and they’re analyzing us in the light of our experiences and we’re analyzing them in the light of our experiences. For example, I find no sympathy for President Nkrumah’s excursions in government in Ghana, even while I might admit that in this transition period, it may be necessary for Africans to have a form of one-party control, or dictatorship, or that sort of thing in order to make the transition – because you just can’t run a government one day as colonials – intensely deprived and being looked after, and the next day they are lords of the manor, and I could – even while I sympathize with that point of view, I can’t go as far as Mr. Nkrumah, who wants to control the judges, to remove the police and to have everybody bow down to him, to arrest people and hold them in jail for five years and ten years. This is the thing we’re condemning in South Africa – and he’s doing exactly the same thing in Ghana. What difference is there between a white dictatorship and a black dictatorship? If you look at it from the man in jail, who doesn’t know what he’s being accused of.

[00:26:09] Warren: It entails – in terms of principle.

Wilkins: Exactly, exactly. So I think, to get back to your question – I’m sorry I’m so discursive –

[00:26:19] Warren: Yes, please, please.

Wilkins: Richard Wright is probably true – it was probably true – his experience, and I think American Negroes are beginning to readjust their views of African Negroes – genuine admiration for men of genuine ability, and not just admiring them because they are Africans. And, I think the Africans are beginning to see that American Negroes have their men of genuine ability and their people of warmth and laughter and friendship and culture, and they have some charlatans and some fast dealers and some corner-cutters – and we’ve found that they have corner-cutters and fast dealers, too. And I’m hoping, and I believe that the situation is improving – the understanding between us. You know, there was a time when Africans hardly concealed their contempt of American Negroes because they said “You’re a second-class citizen in your own country – and we’re free – and we run out country and you don’t run your country. You don’t even run your state. And, they can kick you around, and they lynch you and so on and so forth.” Well, American Negroes acknowledge that a lot of this is true, but they turn around and say to the Africans, “What are you doing with your country, now that you have it?” I think we’re all going to come out on top, so to speak, but right now is a difficult period and I think Richard Wright was having trouble communicating.

[00:28:01] Warren: And he had the candor to analyze the situation.

Wilkins: Yes –

[00:28:06] Warren: Rather than to give a romantic version of it.

Wilkins: Exactly.

[00:28:10] Warren: Let me read a quotation to you, sir, about Negro history. “The whole tendency of the Negro history and movement – not as history, but as propaganda, has been to encourage the average Negro to escape reality. The actual achievements and the actual failures of the present although the movement consciously tends to build race pride, it may also cause Negroes, unconsciously, to recognize that group pride is built partly on delusion and, therefore, may result in a devaluation of themselves for being forced to resort to self-deception.” This, by the way, is by Arnold Rose, Myrdahl’s [Myrdal’s] you know, at –

Wilkins: Yes, I know. At the University of Minnesota.

[00:29:13] Warren: Yes, yes.

Wilkins: Well, I’ve had some disagreement with Dr. Rose’s conclusions for some time – some of his conclusions, I don’t mean all of them – and I – it strikes me that this particular quotation is a little far-fetched. It’s – it bends over triply backwards in order to say that the emphasis on Negro history, while it may – it’s aimed at enhancing pride of race, may eventually result in self-deprecation because it was necessary – and here he makes an assumption – it was necessary to delude oneself as to one’s historical accomplishments in order to build one’s pride.

[00:30:13] Warren: Let’s put this principle over into the South – the American white South. We can see it has worked there very clearly, can’t we?

Wilkins: Yes –

[00:30:26] Warren: The Southern mythology – the old South has certainly been – this myth a great psychic liability to a great many Southerners.

Wilkins: Yes, I think so, but I would say – I don’t believe that the Negro history, as it’s taught – and it’s certainly in its rudimentary stages, and I don’t believe that it is on a par with the playhouse that the Southern white people constructed for themselves in order to rationalize their position in American life after 1865.

[00:31:17] Warren: Or the New Englanders either.

Wilkins: Yes – exactly. The same thing goes. I think the Negroes’ attempt to construct a history is not really for the purpose of perpetuating a stance that he has, or justifying a hold that he maintains in or over someone, or of casting reflection on those who may have, in his estimation, held him back. It has been solely and simply for two purposes – I see it. One, Dr. Rose has mentioned – the instilling of race pride, where there was none. And, second, for information – information – information. I recall here now, Mr. Warren, the fact that only two years ago, three years ago now, we found in Michigan Negro high school counselors, not white high school counselors, who were telling their Negro high school students that they ought not to study chemistry because there was no future for a Negro chemist. This was in the state of Michigan in 1961.

[00:32:47] Warren: Excuse – this is the end of Tape 1 of the conversation with Mr. Roy Wilkins. Proceed on Tape 2.

Collapse

TAPE 2 Searchable Text

Collapse[These digitized texts are based upon 1964 typed transcripts of Robert Penn Warren’s original interviews. Errors in the original transcripts have not been corrected. To ensure accuracy, researchers should consult the audio recordings available on this site.]

ROBERT PENN WARREN ROY WILKINS TAPE #2

[00:00:04] R.P. WARREN: This is Tape #2 of conversation with Mr. Roy Wilkins – proceed. You were speaking a moment ago when we were changing the tape of the matter of confidence in young Negroes or old Negroes in a sense that their history has helped build this confidence.

Mr. WILKINS: Yes, indeed it has. Those who have taken the trouble to read their history have found the struggle was going on before the 1960’s, before the second world war in 1942, and before the first world war, and back even in slavery days the struggle was going on.

[00:00:47] RPW: Let me ask this question in that connection. What accounts for the timing, then, of the so-called Negro revolution the last few years, with this impulse, as you say, existing over a long period of time? What brings it into the open now in a general effective way – highly organized way?

RW: This is the result of an accumulation of events – an accumulation of developments. I think first of all we had the emotional stimulus of the one hundred years since the Emancipation Proclamation – in 1963, you see – an emotional year – a centennial – an anniversary. They looked around them and they said, it’s been a hundred years and look where we are. We aren’t here and we aren’t there and we aren’t there and we aren’t there. This gave a lot of impetus. Secondly we have to reckon I think with the fact that it took a number of years to build up an educated cadre of youngsters, fathers and grandfathers who cumulatively built resistance and resentment against things they suffered. This couldn’t help but explode. After – you graduate a hundred high school graduates this year, you graduate a thousand five years from now, you graduate ten thousand, you graduate twenty-five thousand – you keep on graduating – and finally you get to the place where that number of graduates will say, well, this is untenable, I can’t stand it – we must push. That was one factor. Mr. Warren, you had migrations from the South to the North beginning with World War I, a large number of Negroes came up to Gary and Youngstown and Akron – industrial centers, and they settled down, they became voters and went to school and they sent their children to school. More importantly, about 1930 they became political factors in the Matchkey – in the Republican machine in Cleveland, in the Big Bill Thompson Republican machine in Chicago, in the Pendergast machine in – Democratic, in Kansas City –

[00:03:30] RPW: And the Crump one in Memphis, Tennessee.

RW: And the Crump one in Tennessee, and the Vair machine in Pennsylvania – Republican machine. And Tammany was nibbling and playing with the idea of the Negro – so that he became a political factor. This was a buildup too. All of this was a buildup to the 1960’s. But then you have Great Britain – you had two world wars too – you had a war against – to save the world for democracy, in the words of Woodrow Wilson, and the Negroes came from the swamps and the plantations and the cotton fields and they went overseas and they saw Paris, and they saw Berlin, and they saw Europe, they saw London, and they came back and they knew there was a world outside of their particular county and there were a different kind of white people there and different things were under way. And in World War II you had them fighting against the Master Race theory, and they could go back to Terroe County, Georgia, and find a Master Race theory too. And this was not lost upon them. And finally, in 1960 you had the pile-up from the 1954 school decision, the defiance of it, the refusal to obey it, the attack upon the Supreme Court, the attempt to change the rules after the game had been won. The Negro thought he had won in 1954 – his citizenship had been reaffirmed, his constitutional basis of his life had been reaffirmed by the Supreme Court and said we can’t discriminate on account of race – but discrimination went on, the Southern legislatures passed laws and they obstructed this, that and the other. Finally, in the 1960’s the Negro broke loose and took direct action. He said, we can’t depend on legislatures and we go to the courts and we take fifty years to go slowly through the courts and chip away at the separate but equal, and we win in 1954 but we don’t win. So let’s get out on the streets and take it directly to the seat of government, and that’s what happened. And I believe that’s the reason you have the revolt in the 1960’s and not in the 1950’s.

[00:05:55] RPW: I don’t imagine it would be surprising to you if I should say that a good many Negroes flinch from your explanation – I don’t know how many, but some that I know, because it implies over a period of time a process, you see – the grandfather, the father, and the son, being the cadre of educated people with a will directed toward immediate achievement. This seems to say process always means the gradual and therefore it affects the present, you see – let’s say process, as one young man, a student, said to me in this connection, he said, I understand that a change takes place in time, you see, and that there’s no absolute solution, no immediate solution to any social problem, but he suddenly said, but dammit I can’t bring myself to say it. That is, emotional as opposed to the intellectual grasp of the process.

RW: Yes, that’s true. And I sympathize with that young man absolutely. I know exactly how he feels. But nevertheless, the fact remains that except in certain instances, certain situations, no immediate change can take place – a change in attitudes can be the – either induced or forced or brought about by persuasion, and these changes in attitude will in due time bring changes in fact.

[00:07:41] RPW: And vice versa.

RW: Yes. I feel – I know that the Negro shrinks from the use of this word gradualism, or even the concept of gradualism.

[00:07:52] RPW: Process is a bad word now.

RW: Yes. He doesn’t like that at all. And yet, if he reads history even in this country, he reads the history only of the labor movement, if he read just the history of the struggle for a child labor law, one segment of the labor movement, if he read the story of the struggle of the labor unions to get rid of the injunction, the use of the injunction against them – if he read all the labor struggles prior to the Norris-LaGuardia Act and the Wagner and the labor act, when labor really got its charter in the 1930’s – the middle 1930’s – he would understand that while you never, never, never give up or compromise, that things don’t happen over night.

[00:09:06] RPW: This is a question, then, of what freedom now means – what the slogan can mean – what is its content – it brings us to that, doesn’t it?

RW: Yes, it does, and I think the answer is very – well, it’s not very simple – nothing is simple – freedom now means just that. It means away with the old concepts, it means a beginning of real, solid, good faith beginning on new concepts. I think that young student you were talking to realizes that you don’t change over night, but he wants Mississippi or Alabama or South Carolina or Louisiana to set its face in the direction of change and to make meaningful steps toward change that, carried out successively, can lead to what he wants. Now, he’s very quick to detect – I am, and all Negroes are – very quick to detect those phony steps toward change, those pretensions, those delays, those take-it-or-leave-it, or those teaspoonfuls that they give you here and there, instead of giving you the whole pot of soup. Negroes have no truck with this sort of thing in this kind of revolution.

[00:10:41] RPW: Let’s take the word “revolution” for a moment. In what sense is the – well, the revolution a revolution – we’re fooling with a word now, but behind the word what is the reality? How does this correspond to – how far does it correspond - the French Revolution or the American Revolution?

RW: I don’t believe it corresponds to those, because we are not here seeking to overthrow a government or to set up a new government. We are here trying to get the government, as expressed by a majority of the people, to get the government to put into practice its declared objectives. This is a little different kind of a revolution, it seems to me. We are also not in a revolution, as has been said over and over again – not a revolution of despair but a revolution of rising expectations. In other words, the Negro wants in, he wants to share in the American life. His outpouring in Washington on August 28, 1963, was an outpouring saying let me into the good things of American life – stop denying me. It was not a revolution – it was not an outpouring which said, let’s get rid of this government and put in a new government that will give me a chance.

[00:12:24] RPW: Not to liquidate a regime, but to join a regime.

RW: Exactly so – exactly.

[00:12:29] RPW: There’s another aspect – another problem – that might mean the difference between other revolutions – revolutions live on hope and they live on hate – the hope for the change, the expectation of change – otherwise a servile revolt or desperate insurrection – but a real revolution lives on a hope – a hope of accomplishment. Otherwise it can’t organize itself. It also lives on this mobilizing of the force through hate. It’s the guillotine has to operate – the revolutions of the past – you have to hate somebody. The question now is how the – the hopes are clear in this movement – how the hate side, the drive toward this squirt of adrenalin that makes it possible to act – how that is provoked, channelized and contained if the movement looks toward a joining – its joining with, in one sense, quotes, the enemy. Is there some problem around this side of the matter? Now, it’s easy if you look at Malcolm X – it’s easy there, with the Black Muslims – and it’s easy when you can take an extreme situation going the other way, and take a Quaker, you see, or - it’s easy – extremely simple – it answers itself – now in the great world, the great body of people, with Negroes in between these two extreme positions – the problem emerges in one way or another, doesn’t it?

RW: Yes – yes – I guess so. I don’t envisage the Negro employing hate as a tactic, as a recognized procedure to mobilize support for his side or to win objectives for his side. I of course do not rule out the fact that here and there individually, as between two individuals or in a small group, there might be something akin to hate as a motivation for action.

[00:15:11] RPW: I think we’d have to face that fact, then, that it’s a component of human nature and human There are plenty of provocations.

RW: Exactly – exactly – yes. But I don’t see the Negro in this country adopting hatred as a tactic. In the first place, if he had believed in hatred as a tool, and if he had been on – to a widespread degree subject to hatred or capable of employing it, maintaining it and feeding it and using it, he would have done so long ago. He – I once said about Malcolm X – he was talking about rifle clubs in 1964 – and violence and shedding blood – if the Negro had believed in what he would have used it a long time ago when he was much worse off than he is now.

[00:16:15] RPW: Of course * once, we believe in the nonviolent approach as a matter of philosophy and ethics. Also, he said with his infectious grin, my folks had more guns.

RW: Yes, that’s true, and the Negro has never forgotten the fact. As a matter of fact, the Negro in this country is a very practical and pragmatic animal, and he has never lost sight of the elementary facts of survival, and he never has forgotten that he’s a ten percent minority numerically, and that economically and politically he is a much greater minority than ten percent. So that he does not have the power, except the moral power, to mobilize – how many guns, to put it bluntly – how many guns can he get?

[00:17:27] RPW: But, shall we say, that any movement is always a movement of power. It’s a question of the nature of power – is that it then?

RW: Yes. And he has on his side, and he has utilized I think magnificently, the moral power that he has. He has the power of moral righteousness on his side, and he has something else. The United States is

* “?” handwritten following blank space

vulnerable because of its declared purposes. Now, if he had an ambiguous constitution, or if it had an ambiguous declaration of independence, this would be different. But the Declaration of Independence says all men – now, there were some squabbles over the Constitution, of course – there were some people there who didn’t want it to mean what we now say it means. But this was resolved in the usual way. There are a lot of people now who don’t believe in liquor control, let’s say, or fair price laws, or import duties on watches, - on hides, yes, say. The tanners want duties on hides. The watch people don’t much care whether they have duties on hides or not, and so forth and so on. Well, we resolved this question in our Constitution. But America is on record the haven of all the oppressed peoples of the world. This is the land where you can come and demonstrate your ability and achieve on the basis of your ability. If you’re a Hungarian when you get here you become an American, and if you’re an Irishman when you get here you become an American.

[00:19:16] RPW: What do you think of the notion that some sociologists or historians have annunciated that the American Negro is more like the old American than like any other element in our culture?

RW: Some people have said that, and it’s –

[00:19:33] RPW: The old Yankee or the old Southerner –

RW: - it’s probably true – it’s probably true – he is –

[00:19:38] RPW: He’s an old American too.

RW: Yes, he is, he’s a very old American, and he’s American in his concepts. He’s – I think he’s liberal only on the race question. I mean, I think he’s a conservative economically, I think he wants to hold on to gains in property and protection. I may be wrong, but I don’t see him as a bold experimenter in political science or social reform. He may change once he gets on a period of equality. I think of course he’ll have his proportion of these people, as he now has. There are Negroes who are nonconformists, there are Negroes who are atheists, there are Negroes who are even DeGaullists –

[00:20:33] RPW: How much anti-Semitism do you do you think actually exists among Negroes?

RW: That’s a hard question.

[00:20:42] RPW: I remember the Philadelphia episode and other episodes of the sort.

RW: Well, I find that –

[00:20:48] RPW: I have encountered it myself.

RW: Yes. Basically, Negroes are not anti-Semitic, and such anti-Semitism as he occasionally expresses stems from his own personal experience, like a white man who tells you that Negroes are no good. I knew one once and he did so-and-so to me, or he wouldn’t do so-and-so. And Negroes who make anti-Semitic remarks are those who may have run into, say, a Jewish storekeeper or a Jewish landlord or a Jewish woman who is the boss of domestic servants – these are the three areas in which they come into contact with Jewish families – with Jewish people generally – the landlord, the storekeeper, and the lady of the house where they work. If they have an unfortunate experience with a Jewish housewife, let’s say, they are likely, as most weak people are, this Jewish lady did so-and-so. Well, if they work for an Irish woman or a German woman or a Swedish woman and she did precisely the same thing the Jewish woman did or had the same attitude, they would say, oh, that old white woman – you see.

[00:22:12] RPW: Yes. In other words, they have taken on some coloration of attitude from the floating Gentile white prejudices.

RW: Yes, they have – they have also. But they have never forgotten, for example – I have traveled all over this country – I’ve met thousands upon thousands of Negroes, and have lived in their areas and I know them – they have never forgotten that wherever they have been, whatever kind of trouble they’ve been in, the Jews have helped them – some Jews – either Jewish individuals or Jewish philanthropists or Jewish rabbis. Invariably, when you go into a town and you ask the Negro community, who do you count among your friends in the white community? Among the first five people always a Jewish rabbi – always. He’s the man who understands their problem and sympathizes with them, who speaks to their meetings, who talks to them. So that anti-Semitism among them I feel is not virulent and not hateful, although, like any kind of racial feeling, it is detestable. But it’s not the kind of hate-the-Jew attitude that you find in some people.

[00:23:37] RPW: You don’t think that they exploit it, by, say, a Black Nationalist movement? Is there a serious problem that way or not?

RW: It has been – an attempt – I don’t think so. Now, the Muslims have attempted – they have used anti-Semitism. But I don’t believe they have gotten far. They have mouthed a few catchwords, and those catchwords have been taken up by their followers. But I don’t believe that it has become part and parcel of the Negro community. In fact, I am positive it has not. It just hasn’t taken hold. Now there—even in the deep South you recognize that Jews have helped them, Jews have extended a hand, Jews have made loans to them, Jews have granted them credit, Jews have fought the battle against discrimination where they could – remember, Jews have been vulnerable in the South too. They have not been able at all times to speak out. But in this present civil rights crisis that has developed since the Supreme Court decision in 1954, the Jewish community overwhelmingly has been on what we call our side. Now, there are Jews who are not on our side, Jews who are opposed to us, and who have nothing to do with the civil rights movement.

[00:25:07] RPW: As a Negro in the * said, the country club Jews are against

*The word “audience” is lined through with NO written above it.

us. That’s the way he put it.

RW: Yes. It’s hard to classify them, but there are – any time you have four million people you have all kinds of beliefs, and there are plenty of Jews who don’t want to be bothered with the Negro problem, don’t want to be identified with it, they don’t want the Jews – they don’t want the Jews’ problem tied to the Negro problem.

[00:25:30] RPW: This flight from Jewishness to a degree sometimes, isn’t it?

RW: Yes, but even the Jews – go back to your question of some time ago, about Negroes discovering themselves – I think Jews have come to the place, again – again, where they – and they go periodically, the stray back and forth – but they have come in increasing numbers to Jewishness, to an appreciation of the Jewish worth, to pride in their own faith and religion and in their own accomplishments. I mean, aside from the genuine pride they have always had. But I think – I think the Jews have a feeling of their own that Jews amount to something and Jews are important, and maybe some of them say, as one of them told – a rabbi told me – my congregation told me they didn’t want me to preach on the Negro question because they didn’t want Jews identified with the Negro question. This was a very high type Jewish congregation. Yet, on the other hand, the rabbi of one of the most aristocratic and wealthiest Jewish congregations in the United States appeared on the same program with me and, not because I was there or anything about it, outlined a speech that could have been made by the finest liberal in the United States. So you can’t classify them. You can’t say the country club Jew or the wealthy Jew.

[00:27:07] RPW: A quotation from –

RW: I understand that – I understand that very well – yes.

[00:27:13] RPW: You say liberal among the white friends of – you see. This raises a sort of question about the role of the white man in relation to the Negro movement or Negro revolution. On the other hand you will find such statements as the one made by Mr. Baldwin, the white liberal is an affliction, and Iseley’s fond farewell to the white liberal, or there’s the white man stay home, or Jack Greenberg – all of these – Yankee go home -. On the other hand, you will find them saying – well, go away entirely, leave us alone and we’ll make the choices, we’ll run the show. On the other hand, another attitude saying, if you come you ought to make yourself contemptible, as it were, in one form or another. You are coming, and a person who is – well, best put it this way – in Mississippi, for instance, Robert Moses – of the attitude of the Negroes there toward white helpers form the outside who want to over-identify.* This contempt of the white man’s naïveté – his innocence, his desire to enter, to buddy up, to be one. In other words, the white man can have –

* Question mark handwritten beside this section

these two poles – has no role, you see – if he’s – he says commonly expressed – in one form or another they appear all over the place – and can be associated with the Negro movement in one way or another. That is, the white man can find no role acceptable, you see, to the Negro, in so far as you take these pronouncements and put them all together – he has no place to come close, you see, to join, to affiliate, to help, he has – no attitude is acceptable

Do you see the problem?

RW: Yes, I see the problem. I’m familiar with it, and I disagree very greatly with the –

[00:29:33] RPW: With both of these attitudes?

RW: Basically, yes. I disagree with it, although I understand why it exists in some cases. But I feel first of all that we ought to recognize that white people have been fighting for the liberty of the individual long before the Negro question of liberation every came up.

[00:29:56] RPW: This is a point of considerable importance, that is, the concept was and now it’s a question of application – particular application. Do you understand -

RW: Exactly, well – yes, that’s right. White people, beginning with – long before the Magna Charta – were fighting against oppression and for the liberty of the individual, and they have fought, since we have had our country here, many battles not connected with race. They have fought for freedom of the press, and freedom of religion, and all the sorts of things that they have fought for. We ought to recognize that they have a heritage of protecting and enhancing the Constitution of the United States, irrespective of whether it applies to black people, white people, Northerners or Southerners, and that there can be sincere white people who believe in these principles and want to fight for them, and we ought not to shut them out of our movement because they don’t fit into every niche and cranny of out thinking and our being, and they don’t behave exactly as we feel they should behave as blood brothers – we’re brothers after all in a cause - the cause of liberty. *

[00:31:24] RPW: That is, you are throwing the emphasis on the – if I understand you right - on the conceptual side of it.

RW: That’s part of it. Now, I would come – as soon as we finish here – I would come to the other part about his feeling of – in worming himself in and not being able to adjust, and – let’s come to that.

[00:31:50] RPW: All right, fine. This is the end of Tape #2 of the conversation with Mr. Roy Wilkins. Proceed on Tape #3.

* “NB” handwritten beside this section.

(end of tape)

Collapse

TAPE 3 Searchable Text

Collapse[These digitized texts are based upon 1964 typed transcripts of Robert Penn Warren’s original interviews. Errors in the original transcripts have not been corrected. To ensure accuracy, researchers should consult the audio recordings available on this site.]

ROBERT PENN WARREN - MR. ROY WILKINS Tape 3 April 7, 1964

[00:00:07] Warren: This is Tape 3 of a conversation with Mr. Roy Wilkins. Proceed. All right – you were saying a moment ago, between tapes, that you recognize this problem of the white – the white man’s problem of attitude – how can he make himself acceptable, or in the fact that the Negro – or some Negroes can find no attitude acceptable. What can be done to pass the – test, was test the word you used? –

Wilkins: Yes, yes.

[00:00:32] Warren: Let’s go back to that a moment.

Wilkins: Yes, I don’t know whether I would choose the word acceptable, because it implies – it seems to me – that the Negro is imposing a test on white people for a particular reason, and that he must conform to certain criteria in order to be accepted, but –

[00:01:02] Warren: But don’t some Negroes do that? From their statements in the press and elsewhere?

Wilkins: Well, some do, some do, and – but, of course, I feel, Mr. Warren, we ought to recognize that in the present state of Negro-white relations, and the scramble that’s going on to get on record and to be understood and to be uncompromising and to be militant and to be demanding and to be all the things that are now regarded as the things that you have to be – people say a lot of things in public about white people have to conform to this – white people must give up – white people must recognize – white people must, must, must, must. This is a sure way to get on television and to get quoted and to cause tremors in some quarters – or, at least, if not tremors, head-scratching and soul-searching. But I believe, as I said, on the other tape, that the Negro must recognize that there must be some sincere white people interested in the liberal cause and in the cause of freedom, irrespective of whether race is involved or not. They have given too much blood and made too many sacrifices for the right of freedom of religion – for the right of a trial by jury, for the right to vote and to have the kind of government that will represent their views, for freedom of the press and for all the things that they hold dear. They have fought for these things and bled for them and died for them, and if they now step forward and say, “We want to include in our beliefs also the belief in Negro equality, or equality of opportunity for the Negro, or placing the tent of the Constitution over our Negro citizens” – if they now step forward and want to do this, I think we ought to examine sincerely whether they are opportunists – or phonies, or pretenders, or Trojan horses, or whether they are sincere, and I don’t go with this idea of dismissing all white people as being insincere, or trying to climb on the band wagon or trying to make a point – or trying to make a profit – or trying to use you – or this – some of them are, freely admitted, but there sincere ones and we can use them, just as all fighters for the extension of human liberty can use all hands. Now, as to this other thing, about ingratiating themselves and about the difficulty of adjusting themselves to – or, their apparent haste to ingratiate themselves in the new movement, here again I think we have to use caution, because in one breath we are saying one of the great troubles in the race question is the lack of communication. They don’t know about us, we say. We know about them, we’re so sure, but they don’t know about us. Now, when they come over and try to find out about us, why don’t we teach them, instead of saying to them, “We look on you with suspicion. You’re just trying to ingratiate yourselves. You don’t know how to get into the Negro world. You’re awkward and you – we look down on you – we laugh at you.” Is this the way, when you say the prime obstacle has been lack of communication and people come who want to communicate? Wait until you find out whether they don’t want to communicate.

[00:05:11] Warren: Is there some implicit resentment on the part of Negroes at the assumption that a certain percentage of the whites who want to identify somehow come as what Lenin called, “with the pathology of the left” – they’re coming with some compulsive neurotic reason – some insecurity of their own – something that drives them, so that it is not a free act.

Wilkins: I think so.

[00:05:42] Warren: You think there’s something in that?

Wilkins: I think there is.

[00:05:44] Warren: Suspicion?

Wilkins: I think so. I can’t define it – I can’t –

[00:05:47] Warren: You sense what I mean?

Wilkins: Yes, indeed. I think there are people with axes to grind, other than the axes –

[00:05:53] Warren: There are emotional axes, not money-making, or condescension, but something –

Wilkins: Right. They may have ideological axes. They may feel that what’s wrong with the world is that we need a new system, and that if I can recruit the Negroes in their extremity, -

[00:06:10] Warren: There’s the Communists. I’m talking about the man now, who comes with an emotional need of some pathological order you see, that must be gratified by this –

Wilkins: Yes, there are some of those too. There are some of those, but they all show up in time, and it’s easy to identify them sooner or later. The Negro can spot the genuine article. I’m only saying that he ought not to meet all newcomers with this blanket suspicion, or blanket condemnation. It’s easy enough to sort out the emotionally disturbed, let’s say, or the political leftists, or the political centers, or whoever they are later on. But, I feel that if he has a chance to do evangelism, he ought to do it. He has a lot to talk about and his cause is identified with the best ideals of America, so that they’re good for the white people as well as for the Negro, and he ought to preach this.

[00:07:15] Warren: Suppose, Mr. Wilkins, tomorrow morning we woke up and found that the Civil Rights – a good Civil Rights bill, one that would be satisfactory, had been passed and that there were fine enforcement agencies in operation and fair employment was enforced, the laws about fair employment and a reasonable, even a willing acceptance in general of this, and we had our schools all integrated – what remains? Quite a long way –

Wilkins: That’s a long way.

[00:07:53] Warren: What remains? After that?

Wilkins: What remains of course, is for the Negro to become and the white people too, in the sense that their Negro development has been neglected – but what principally remains is for the Negro to make himself with this opportunity, with these barriers down, with the help of new legislation, to speed on the process of self-development and self-discipline, so that he becomes a contributing, a more contributing member of society than he is now.* He now contributes, of course, but he assumes broader duties than merely duty within the Negro community. He assumes, if he is a successful business man, he assumes what a successful business man assumes for a community development and responsibility, and he becomes concerned with hospitals and health and traffic and profits and manufacturers and banks and all of the thing that go to make for community and state and national development, aside from being a Negro. Now this takes time, Mr. Warren, to

* … King handwritten in margin by this section.

develop this, because when you come out of a ghetto, not only a physical housing ghetto, but a ghetto intellectual and ideological – and you’ve been excluded from the mainstream of American life, it takes a while to find out how to function, outside of the ghetto. I recall years ago, when I was in Kansas City, in the campaign for the Community Chest, the sales argument in the Negro community had to be what we Negroes get out of the Community Chest. This was the way you could sell it in the Negro community. You had to point to the various agencies and institutions and how you got something from the Community Chest, in order to get five, ten, fifteen or twenty-five dollars from them. Now, in the day that you’re talking about, it will not be sold to Negroes – the Community Chest, or community project – will not be sold on the basis of what you get out of it, hopefully. But – what can you do for it and for the community?

[00:10:39] Warren: A sense of community identification in a full way.

Wilkins: Yes. There are Negroes who now already have that identification in many communities. You find them assuming their roles and sometimes suffering derisive comments from their brothers on how they have removed themselves from racial life, let’s say.

[00:11:05] Warren: This is not uncommon, is it?

Wilkins: No, it’s not uncommon. And, it’s – but it’s not as widespread as it ought to be. By that I mean, I want to see more of them assume more of their community obligations. I think, for example, the South is – one of the things the South has neglected is to estimate what this Negro can contribute to the South. He’s there – he has talent. Why should he have to migrate from the South to exercise this talent in Chicago, or in Pittsburgh?

[00:11:44] Warren: That’s true of a lot of the white population, too, you know.

Wilkins: Exactly so. They have come away. That’s true.

[00:11:52] Warren: It’s exported black and white talent of all kinds.

Wilkins: Well, they have come away largely because of economic – some of them – because of economic opportunities. They can get – your bigger salaries in Philadelphia and Washington and New York than they can in Meridian or Dothan or in Panama City, Florida, let’s say, or in Tyler, Texas. And, some few of them have come away because they couldn’t stand the climate. But the Negroes have been driven away, not only by the drawing of better salaries, but mostly by the treatment. Now, the South could save this talent and help to build the South – it needs the Negroes. It needs their manpower; it needs their life, their laughter, their warmth. It needs their indigenous identification with the South. They can be a tremendous asset to the South and in fact, they are now; they contribute, however, through a screen. Through white people. But they could contribute for themselves.

[00:13:02] Warren: Some weeks ago I was talking among others, along the way, to Mr. Evers, Charles Evers. And, I asked him why he stayed in Mississippi. He said, “I think things are going to work out here fairly soon.” I don’t know what fairly soon is, but – he said, “We’ll have a settlement here that’s satisfactory, probably before you can get it in some other parts of our country.”

Wilkins: Well, this is a –

[00:13:37] Warren: See, they analyze the Mississippi character.

Wilkins: Yes. This, Mr. Warren, is –

[00:13:43] Warren: I wouldn’t want to make book on it.

Wilkins: No. This is the echo of a hope that has existed in many areas in the South.* Years ago a man said to me, “The first breakthrough in the South will be in Texas, because Texas is more Western than Southern and it’s more individual and as soon as they’re convinced that this thing is no good, they’re going to throw it over. Well, I don’t know. It took Texas a long time to wake up, and they’ve made some progress there – but breakthroughs have been made in Atlanta, as we just mentioned. Breakthroughs have been made in North Carolina. The University of North Carolina has quietly taken on a good many Negro students, without any fanfare. The University of Arkansas, interestingly enough, without any lawsuit, without any bitterness, without any tension, admitted Negro students to medicine and law and opened up the University to them. And, you haven’t heard a peep out of Fayetteville,

…… written in left margin

Arkansas, since who laid the rail. Nobody has said boo about desegregation, mobs, fights, arguments, committees, petitions, picketing, demonstrations, marching – never hear it. The University of Arkansas has gone quietly ahead. Now, for Mr. Evers to say that he hopes that he hopes that this will take place in Mississippi he thinks, is the kind of thing that we all hope; I wonder how it can happen as I look at Mississippi’s resources. I don’t doubt that there are white people in Mississippi, who would like to see some changes take place, but I see a massive political machine in Mississippi.

[00:15:41] Warren: There’s one.

Wilkins: Built upon, strictly upon white supremacy and keeping the Negro down.

[00:15:51] Warren: James Baldwin writes in his most recent book that the best testimony, the testimony of those who are actively engaged in the Civil Rights struggle in the South, is to the effect that the Southern mob does not represent the will of the Southern majority. This is Baldwin’s statement.

Wilkins: I agree with him.

[00:16:14] Warren: You agree with him on that.

Wilkins: I agree with him. I think the greatest trouble in the South, the biggest obstacle in the South is not the so-called white rank and file man, who demonstrates occasionally against the Negro, but is the Southern political oligarchy. They’re the ones that have the stake in this thing, and it’s not only a stake of control over the Negro population as such. That’s only incidental – and I think if the white population ever woke up in the South to the fact that the political oligarchy has used the Negro scare in order to perpetuate control over the entire Southern hegemony, I think we’d see a real revolution there, if they ever recognized this.

[00:17:12] Warren: As one Negro – a Negro college president said to me a few weeks ago – he was talking, he’s been talking to a certain politician who said, “Look, I can’t do that now,” but said, “if you can get two hundred thousand votes, I’ll do anything you say.”

Wilkins: He’s right. That’s right. Now they – that’s true. Now, the spokesman in the Congress against the Civil Rights bill now – the senators, among the nineteen senators who are committed to vote against the bill, no matter what happens, no matter what arguments are made for it, and no – among those nineteen, there must be a substantial number – I won’t venture any number, who really couldn’t care less if this bill passed, who really honestly would like to see it, or something like it passed. But, they don’t dare.

[00:18:05] Warren: Some Southern politicians have said this privately. “Well, get me off the hook then.”

Wilkins: Yes. Mr. Fulbright, Senator Fulbright, speaking at the University of North Carolina, during April, early April, was asked after his talk there by the students, “Why didn’t you extend your attack upon myths in foreign relations to the myths in racial policy? Why don’t you attack those? Don’t you know that there are myths?” And he admitted that, more or less, that he did, but he said, very succinctly, “If I attacked those, I wouldn’t be here tonight.” He meant as a senator, of course.

[00:18:49] Warren: He signed the Southern white, Southern Senators’ … round robin … he was for …

Wilkins: Yes, the manifesto, yes, he signed it. He’s done everything that a good Southern white senator is supposed to do. He’s done everything. He’s voted right as far as the segregation is concerned, and he has kept quiet on various things and he has spoken out when he had to against the Negro.

[00:19:15] Warren: How do you interpret this, morally speaking, and otherwise – Fulbright’s behavior?

Wilkins: Well, personally, Mr. Fulbright has been a great disappointment to me because he is a living argument against those who say that if a man has culture and education and contact and travel, he can’t be the same as the man who doesn’t have those things.

[00:19:52] Warren: Now I asked Mr. Nevins, Allan Nevins; I known him some years, right after this book, this – he signed this thing – “What do you make of this?” He said, “He couldn’t do otherwise. He had no right to do otherwise. It would have been self-indulgent. He can’t afford to commit suicide and put an inferior man in his position. He’s needed.” Now Mr. Nevins’ views on the race question and so forth – you know what they are – he’s not – this is a complicated remark, it seemed to me, coming from him.

Wilkins: Yes, it is. But, you see, I feel that a Rhodes scholar and a university president and a man of the scholarship and breadth of vision of Mr. Fulbright, and I take nothing from him in those areas – a man who knows the world and who knows – who knows that this little peanut policy of racial oppression can’t stand. He knows that. He knows it’s demeaning. He knows it’s irritating. And he – if he had a free choice – if he were a free man, he may not get out – he might not get out and crusade against it, but he certainly wouldn’t have no part in sustaining it.

[00:21:02] Warren: You think he should have committed political suicide and been an example then on the issue?

Wilkins: I don’t know that he should have done that, Mr. Warren, but I do know this –

[00:21:11] Warren: It would have been political suicide if he had –

Wilkins: It would have been political – if he had come out, and yet, somebody has got to commit political suicide in order to drive home this thing, but, nevertheless, I don’t know whether I want him to make that sacrifice or not.

[00:21:23] Warren: That’s Mr. Nevins’ point you see.

Wilkins: Yes, I don’t know whether I want him – but, I do think this: I think he might be more of a spokesman for what is euphoniously called the moderate point of view in the Senate than he has been. I think, if a man feels that he has to maintain himself despite all the crudities that he has to subscribe to, or has to maintain himself by subscribing to those crudities, and he really actually doesn’t believe them – then he owes it to himself to do some – there are men in the Senate from the South who have said a little word here and a little word there –

[00:22:05] Warren: Tennessee –

Wilkins: Exactly. Now like Tennessee, Ralph Yarborough in Texas, and you’ve had some remarks from some of the other senators, not – they’ve been oblique, they’ve been tendencial, but for those who read between the lines, or as I say – read upside down and you have to read upside down when you read the Southern white politicians’ remarks on the race problem, you can see that what they’re trying to say. Mr. Fulbright hasn’t done even that.

[00:22:37] Warren: How do you define the “moderate position” (in quotes) in the South? How do you define a moderate?

Wilkins: I don’t know that I –

[00:22:47] Warren: You just used the word –

Wilkins: Yes, I did, and I don’t know that – I think that I was falling into the popular colloquialism. I suppose a moderate in the South is a man who is for change – who recognizes that things cannot go on as they have been, but who isn’t for as much change as Roy Wilkins of the N.A.A.C.P., let’s say.

[00:23:16] Warren: But strangely enough, he’s sometimes called a moderate, too.

Wilkins: Yes, I know I’ve been called a moderate, but I always reply to that that the NM.A.A.C.P. and our position here has sponsored the most radical idea in the twentieth century – that is, the idea of eliminating racial segregation from American life. The idea of reclaiming from the Constitution that affirmation of status which is contained in the thirteenth, fourteenth, fifteenth amendment. So that – I’m not concerned particularly with these labels that the latter-day crusaders bring upon us. I remember the days when we were the only voice crying in the wilderness, and when these same Negroes, or their like –

[00:24:12] Warren: You still – they – the N.A.A.C.P. still carries the greatest weight of opprobrium in certain quarters than anything you could name.

Wilkins: Oh, we get more cussing out than anybody else, and –

[00:24:24] Warren: Yes, in Greenwood, Mississippi, for example.

Wilkins: Oh, indeed, not only in Greenwood, but in any state legislature in the South, except –

[00:24:33] Warren: It’s known – this point – you have –

Wilkins: It is known, and we are considered to be the embodiment of the people who want to change our – overthrow segregation, and rightly so, because we have been – I say to you that the Negroes who now, their prototypes in our day, would not joint the N.A.A.C.P., would not come with us because we were judged to be too dangerous, too radical and so forth and so on. I think there’s more to this question of the negro than just fighting to level the barriers and you have to bring some statesmanship, or some thought, whether it’s statesmanship or not to the problems that accrue along with the fight.

[00:25:30] Warren: Yes. You know the quotation attributed to you – “N.A.A.C.P.” – “They” – that is the S.N.I.C. corps” furnish the noise. The N.A.A.C.P. pays the bills” Bail, and so forth.

Wilkins: Yes, when I made that –

[00:25:45] Warren: Yes – “Here today and gone tomorrow.”

Wilkins: Yes, this was a speech in Alexandria, Virginia. And, when that speech was made this was an accurate statement. We had just finished bailing out some of the S.N.I.C. kids in Macomb, Mississippi, who went off on the independent tangent of their own, without consulting us, without plans, or without anything and then when they got in the six-thousand dollar bail bond trouble why they screamed for old N.A.A.C.P. to come down and help them out, and it applied particularly, and I tried to do this in Alexandria – it applied to our unfortunate experience with some members of C.O.R.E. in Louisville, Kentucky, where we were on a joint demonstration, which was billed, however, as a C.O.R.E. demonstration. I wish I knew the secret of C.O.R.E.’s ability to get newspaper publicity. I’d like to hire whoever they have over there to come over and work for us. We had a demonstration in Louisville, Kentucky, in which two hundred and sixty-seven people were arrested, and two hundred and fifty-five of them were N.A.A.C.P. youngsters, youth people. That’s another thing that sticks in our craw. Most of our young people have been involved in all these matters and – but the credit has gone to other organizations. But, anyway, only twelve people out of this so-called joint demonstration were identified with C.O.R.E., and yet when all the shooting was over and all the hooting and hollering was done, we not only get none of the credit, but were left with the legal bill of some five or six thousand dollars. Now, since that time, the picture has changed to some degree. When I made that speech, it was accurate and well-founded and it was based upon not all of our unilateral experiences with C.O.R.E. or with S.N.I.C., because others have been happier, but these two things did stick in my craw, and it’s a little tough to find yourself vilified and sneered at as a kind of a knitting old lady, over in a corner, while the revolution is being carried on by us strong men, and yet called upon to bear the financial burden. And, so I was speaking to my Alexandria chapter for their edification and education.

[00:28:31] Warren: I’ve heard the same thing said elsewhere by other people – for instance, I think she is the president of the local chapter in Bridgeport. Dr. King rallied there a few weeks ago, while waiting for him to return from Hartford, with a lot of speeches in-between. Unless I’m mistaken, she was – the lady who was speaking, and – the N.A.A.C.P. was in tonight, was here in ’23 and in ’33 and ’43 and ’53 and is here in ’63 and you know, this same – same notion of – what about Lomax’s analysis of the N.A.A.C.P. in his book? The one … vote.

Wilkins: Strange to say, I haven’t read it. Mr. –

[00:29:15] Warren: It’s probably predictable – I think –

Wilkins: Yes, well, I know Mr. Lomax’s position if you can call it that, but I’m afraid I’m unable to agree with Mr. Lomax on any except very minor aspects of this whole business. I regard Mr. Lomax simply and solely as a recorder, as a writer, as an observer of the passing scene, who has made a very good thing out of it financially. He’s written articles, written books, he’s lectured. He has so many lectures, he has to go through a lecture agency and charge a regular fee and he says sensational things and challenging things and frightening things to titillate his audiences, and, in so doing, he has made several references to the N.A.A.C.P., and his analysis of our role is totally and completely inadequate because it is based on his own personal, subjective estimate and not upon records. He has never been here and consulted any records that we have and I’m afraid that I would have to discount sharply his estimate of the N.A.A.C.P.’s role.

[00:30:53] Warren: I was thinking of his analysis of the structural organization, of the organization of the N.A.A.C.P. and it’s relation to main authority, to Federal authority, the lack of a democratic organization, is one of the charges he brings against it, of course.

Wilkins: Oh, well, this of course, is absolutely –

[00:31:11] Warren: One of the many of course.

Wilkins: This is absolutely nonsensical. The only organization that has a democratic structure – and this is the N.A.A.C.P. As a matter of fact, I think sometimes we have too much. We are the only organization that elects our board of directors, and we elect them through an elaborate mechanism that stems directly from our convention, which is represented by our membership and our branches, and for – I don’t know what anybody could say about the N.A.A.C.P. and the democratic process, because no other organization I know – I won’t name any – no other organization I know has the elective process and the popular referendum and convention that we have in the N.A.A.C.P. Nothing is rigged at all in it.

Warren: If my memory tricks me, I’m sorry. That is not the impression I carry away from his book. I haven’t read it in quite a little while, but he turns to analyze the structure, professes to analyze the structure – and comes up with this notion of some device of control you see.

Wilkins: Yes, yes. I know, and in one breath he says, “The N.A.A.C.P. is controlled from the top and dominated.” – and in the next breath he says, “The Negro revolution is carried on by the N.A.A.C.P. branches, and irrespective of what New York wants.”

Warren: This contradiction is there.

Wilkins: Yes, and not only that, but he goes on further to say that the ideas for the Negro revolution, as he calls it, and that was his title, have come up from the ranks of the N.A.A.C.P. instead of from the top, and that it ahs been accomplished in spite of the opposition or control – and as in quotes – of the New York clique, or whatever he calls it. This is also ridiculous and any casual examination of our records and – would show that through the recommendations, through the resolutions adopted at our annual convention, this is the most democratic – and as a matter of fact, the N.A.A.C.P. so-called national leadership has been pleading – yes.

Warren: Sorry – end of third tape. Conversation with Mr. Roy Wilkins. Proceed on Tape 4.

Collapse

TAPE 4 Searchable Text

Collapse[These digitized texts are based upon 1964 typed transcripts of Robert Penn Warren’s original interviews. Errors in the original transcripts have not been corrected. To ensure accuracy, researchers should consult the audio recordings available on this site.]

ROBERT PENN WARREN – MR. ROY WILKINS Tape 4 April 7, 1964

[00:00:00] Warren: This is Tape 4 of an interview with Mr. Roy Wilkins. Proceed.