Ellison discusses Du Bois's theory of African American's "double consciousness," concluding that African Americans must determine how they might influence the American culture that is one-half of their consciousness. He suggests that it is fully possible to be proud of one's African American heritage and to wish for full absorption into American culture. Ellison expresses displeasure with commentators who claim that African Americans have recently discovered their courage. Ellison and Warren discuss whether and how integration will change the South and southerners, and they consider whether integration will differ by section. Ellison explains African American resentment of white people who adopt or appropriate African American cultural forms. He also discusses the nature of African American leadership of the civil rights movement. Ellison contends that there has been a shift in white attitudes toward African Americans. He voices support for nonviolence, claiming that there is power in humility. Ellison also discusses African American identity and African American families.

Notes:

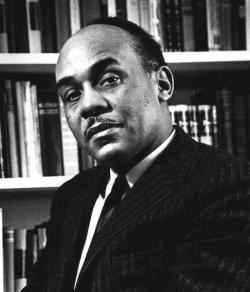

Photo: Bureau of Public Affairs, United States Department of State.

Audio is available for conversation 1, tape 2. The transcript of that tape is missing.

Transcripts, but not audio, are available for the remaining three tapes (conversation 1, tape 1; conversation 2, tape 1; conversation 2, tape 2).

At times Warren can be faintly heard but Ellison can be heard clearly throughout the interview.

Audio courtesy of Yale University.

Ralph Ellison

Ralph Ellison (1914-1994) was a writer and university professor. A native of Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, Ellison was named for the essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson. Ellison studied classical composition at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama from 1933 to 1936, when he moved to New York and began working with the Federal Writers Project. After serving as a cook in the Merchant Marine during World War II, Ellison wrote numerous short stories. Random House published Ellison's Invisible Man, a book that took him seven years to complete. The book, which is an account of a young African American's awakening to racial discrimination, received much acclaim and won the National Book Award for fiction in 1953. Ellison befriended Robert Penn Warren while the two were both in residence at the American Academy in Rome in 1956 and 1957. Ellison taught creative writing at New York University and also taught at numerous other institutions, including Bard College and Yale University. At the time of his death, Ellison had been working on a second novel for forty years. His second novel, Juneteenth, was published posthumously in 1999 under the editorship of his literary executor.

Transcript

CONVERSATION 1, TAPE 1 Searchable Text

Collapse[These digitized texts are based upon 1964 typed transcripts of Robert Penn Warren’s original interviews. Errors in the original transcripts have not been corrected. To ensure accuracy, researchers should consult the audio recordings available on this site.]

ROBERT PENN WARREN RALPH ELLISON TAPE #1

MR. WARREN: This is a conversation with Ralph Ellison in New York City, February 25th. Ralph, shall we begin by – let me just give a quote from Du Bois a while back – he said this in a number of different ways, but this good enough I guess – the Negro has long been divided by a dilemma as to whether his striving upward – it should be a Negro group – should be aimed at strengthening its inner cultural and group bonds, both for and for offensive power or whether he should seek escape whenever and wherever possible into the surrounding American culture. Discussion on this matter has been American culture rather than last sentence the question of the split psyche and all that in many ways. I think I know your line on that but I’d like to hear you rephrase it if you will.

MR. ELLISON: Well, I think this – that it’s a little bit more complicated than Mr. Du Bois thought about it. That is, there’s no way for me not to be influenced by American values, and they’re coming at me through the newspapers, through the books I read, through the products that I buy, the television programs, through all the various media – through the language, of course. What becomes a problem, of course, is that when you turn from the cultural, the implicit cultural pluralism of the country, to politics, social customs, then there is a certain value, but it seems to me that the real pressure is to achieve on the socio-political level the same pluralism which exists on the level of gossip. I don’t see it working any other way. And the idea that the psyche is split is not as viable as it seems. It’s much too easy. My problem, as I said, is not whether I will accept or reject American values. It is, how can I get in a position to have the maximum influence upon those values. And my guide to that is not as arbitrary as I would like it to be, but it’s determined by what my experience is in the country and where I stand, about what I can do and cannot do.

RPW: In your controversy with Irving Howe you of course touched on this – not only touched on it, you developed it. You developed it in somewhat different terms, but it’s the same thought, isn’t it?

RE: Yes – yes – right.

RPW: The matter is a matter of the human absorption without reference to – without the question of official identity as Negro or official identity as American, is that right?

RE: Right.

RPW: You encountered this – you always encounter it in print and sometimes encounter it face to face – a Negro who will say he has regrets at the possibility of loss of racial identity – of absorption – of long-range absorption.

RE: I don’t think it works that way. I think it’s a fair – I think that there are principles of selection which will assert themselves despite the absence of outside pressures. That is, - just on the esthetic level, there are certain types that you like, there are certain sounds of speech, your voice, of nuance – there are a number of things – and then there are the old Freudian concepts that boys tend to seek women who remind them of their mothers. I don’t know how far I’d want to follow that, but I think all of this goes on too. And the other thing is that Negroes, despite what some of our spokesmen say, do not dislike being Negro. I don’t see it as standing in the way of my being as much an American as I can be. If the absorption occurs, other people will have to have given up a lot of their resistances.

RPW: As you have taken the line before – most recently with the articles – exchanges with Irving Howe – that it’s not merely suffering and deprivation, it’s a challenge and enrichment.

RE: Yes – indeed. As I was telling the kids this morning at Rutgers, I’m just too interested in how it’s going to work out, and I won’t impose my will upon it to the extent that I can. I want to help shape it, not merely as a semi-outsider but as one who is in a position to have a responsible impact upon the American value system.

RPW: Well, of course, you’ve already implied this isn’t what some leaders say but am I understand that some of the presentation is in terms of tactics – - the presentation – the total agony.

RE: Yes, well, this becomes part of the strategy of exerting pressure. There is a danger in this, of course – the danger is – in emphasizing the extent to which Negroes are alienated, and to which the racial predicament imposes an agony upon the individual. This being available to political manipulation can be a source of power, and it’s being asserted as such within the present struggle. However, there’s another aspect of it. The American Negro has a dual identity, as most Americans have, and the – it seems to me ironic that the split and the discipline out of which this present action is being exerted comes out of a – does not come out of simply agony – it comes out of long years of learning now to live with pressure, to deal with provocation and with violence, and it grows out of the necessity of establishing a value system and a conception of the Negro experience and of Negro personality which does not always get into the sociology and psychology .

RPW: As I understand this, then, it, that – I think I can get it – that the power of organization, of character, of self control – all these qualities that are making this – the Negro movement now effective, did not come out of blind - it came out of something that absorbed those elements, is that right?

RE: Exactly – exactly.

RPW: It didn’t come out of self pity.

RE: It did not come out of self pity, and it did not come out of self hate, although some of these elements, being human, would be found within it. But when the world was not looking, when the country was not looking at Negroes, and when we were restrained in certain of our activities by the interpretation of the law of the land, something was being – was there to sustain us. When you go back and you look at the expression, look at the folklore, look at the – listen to the music, listen to those tales which are told by Negroes among themselves, you get a totally different person. I’m so annoyed whenever I come across a perfectly well meaning figure saying, well, the Negro has suddenly discovered courage. They make it a dramatic event. Suddenly they are looking at it and so they say, well, Negroes are doing so-and-so. I remember when I was riding freight trains through Alabama to go to Tuskegee, was a well known figure and he was a rough figure in Birmingham. You always hear the stories about from the boys from Birmingham who were at Tuskegee. But you also heard – which I don’t hear any mention of these days – is events of violence between Negroes and whites in Birmingham and the outcome. And one story that was told over and over again was the story of Ice Cream Charlie. Ice Cream Charlie was a manufacturer of ice cream and he must have been very good. It led to his death. His competitors ordered him not to sell his ice cream to white people. The white people wanted it and he sold it, and it ended up with them sending the police after him, and he killed twelve of them before they burned him out. Now, there are many, many of these stories which are in the possession of Negroes and they are part of how we looked at ourselves – nonviolence notwithstanding. This, too, is present, and the memory of Negroes is continuous. It’s just like the white - they remember what has gone on. And we remember. We know what’s happened to us.

RPW: Let me – you started so many things there – let’s pull one or two of them out to pursue. Let’s come back to the question of violence – a separate topic. But the matter of identity, the matter of alienation – those topics were mentioned. What do you think of the suggestion that part of the Southern resistance is a question of maintaining identity not based on the question of race as such. I’ll try to put it another way - - Southerner who feels himself as Southerner as opposed to American – that’s still the Southern psyche he discovers identity is involved, he somehow a lot of things in one package being Southern – one of those many things which he is segregation. He doesn’t realize that this is not necessarily concomitant to having an identity. He associated his love for which he presumed constituted identity. A large part of his existence is based on and his culture and his identity. But the problem might be alleviated considerably. What disintegration of this love idea could take place? Does that make any sense to you?

RE: It makes a lot of sense to me, because one of the areas that I feel, and I think I see when I look at the Southerner who has these feelings, is that he has been imprisoned by it, and that he has been prevented from achieving his individuality, perhaps more than Negroes have. And this is a tough one for Northerners to understand very often – that is, Northern whites, and sometimes even for Northern Negroes.

RPW: I think it is too – some of the people I know.

RE: Yes, it’s very difficult to get that across, and if it could be spelled out, if we could break this thing down and see that segregation isn’t going to stop people from being Southern, it isn’t going to stop the main current of the way of life, because as I have seen the South as a musician and as a waiter and so on, some of the people who are most afraid of Negroes invading will never be bothered because that way of life is structured in a way which is not particularly attractive to Negroes.

RPW: One thing that Van Woodward said to me yesterday in a conversation at lunch, was that a lot of fear in the South is primarily a fear of one of the white men – or a large part – but the fear is some secret pressure in one sense or another about something isn’t a real issue. Does that make sense to you?

RE: I think it does. I think it does.

RPW: a Negro suspicion among whites has set in to prevent a normal, free expression of opinion or personality.

RE: Yes. Because if you say that, all right, I feel that this might work, then the whole structure seems threatened.

RPW: That notion, an interlocking structure, interlocking structures supported just one thing now of segregation.

RE: Yes, and it’s so unreal, actually, when you see the whole political structure being changed anyway, and when the political structure changes it’s going to be seen where Negroes were stopped and where they’ll go. What isn’t appreciated sufficiently I think is that over and over again Negroes of certain backgrounds take on aristocratic values. This is one reason why we don’t have a real middle class.

RPW: That’s been one of the things that have been commented on by observers from the 18th century on.

RE: But over and over again, my intellectual friends they have no conception of this. They can’t understand – I mean, it appears ludicrous to say that so-and-so is an aristocrat in his image of himself and in the values which he has taken over from the white South. Nevertheless it’s true, and some of the biggest snobs that you could run into are some of these poor Negroes – well, they might not be poor actually, they might be living very well – but there are certain things, certain codes, certain values which they express and they will die by them. And there’s quite a lot of that.

RPW: Speaking of codes which are inherited, I had a conversation with Mr. Evers – Charles Evers, ten days or so ago, two weeks ago – he got off on the point of what hope there was for Mississippi and for the Negro in Mississippi – He said there’s a good deal of hope here, some real hope here, otherwise I wouldn’t be here – to paraphrase it. He said, one thing about even the most died-in-the-wool [sic] segregationist, he said, despite the number of and cowards anywhere, but these people are raised on some kind of old-fashioned tradition or notion of courage. He said they’re really taught to respect it. He said when they get the notion that this Negro is standing up to them, is showing courage he said they have to have respect for that fact. He said they won’t have to like it but there’s a base of respect there. He said this is Then he went on to say in the same breath almost, that when you sit down with this same died-in-the-wool [sic] segregationist and talk, talk but he won’t like it. He said he won’t bother to lie because it’s across some line in himself. He thinks there’s something to build, you see. He says that’s why I’d like to stay here. He says there’s some hope. Does that make any sense in your experience?

RE: In my experience, yes, and it’s been – well, it’s part of the Negro folklore – But if you can get one who makes up his mind to be fair, you can talk to him and he’ll tell you the truth, and you can depend on it. He’s not going to back out. And this is said very frequently now by Negroes when they run into difficulties with Northern liberals – Northern white liberals.

RPW: That’s the – Mr. Evers said he preferred this man – those who he said up North would pat you on the back and tell you how much they’re for you, and then that’s all.

RE: This is true. Of course, one part of the Negro’s given such situations, is that he has been known – how this man differs from the other. You know, he’ll say if you get them together, he’s going to talk as much segregation as anybody else. But this one you can go to and he will come through in the clinch. This is I would say built in to people who have to live in the South. That is, you’ve got to know who can help and who might even keep somebody from doing you in. And there have always been that type of person.

RPW: Who were acting out in terms of either simple decency as opposed to theoretical decency, or acting out in terms of a paternalistic, patronizing sense. This again can involve character -

RE: It can involve character, and cause. But the person – the Negro making the judgment is making the judgment.

RPW: It’s important for him to make that judgment.

RE: It’s very important for him to make that judgment, and it’s very important for him to know more about that man than perhaps the man would suspect that he knows.

RPW: Or knows about himself.

RE: Or knows about himself.

RPW: Let me pull another conversation I had a while back – in Washington I was talking to a Miss Lucy Thornton, a very brilliant young lady, second in her class in the Howard University Law School, and she’s been through the demonstrations, she’s been in jail and so forth. She was raised she said on a farm in Virginia, and when I first met her – we were sitting at a luncheon together at a long table- there were fifteen or twenty people there – she turned to me and said, I’m not optimistic about the way things are probably going to go here – or may go here, she said, about getting a human settlement after the white troubles are over. I said why? And she said, well, because we have been on the lam together. She said, we have a common history which is some basis for communication for living together afterwards – some human recognition – that was the idea. And she went on to say, I’m very much afraid in Detroit and Chicago. She said, from my background I don’t see where this recognition can come in – I don’t see the basis for it. Now,

RE: Well, it is true that when you share a common background, a common culture, you don’t have to spell out so many things, even though you might be fighting over recognizing the common identity, and I think that that’s what’s part of the South – part of the South’s struggle. It’s just very hard for Governor Wallace to recognize that he has got to share not only the background but the power of looking after the state of Alabama with Negroes who probably know as much about it as he does.

RPW: Pathologically.

RE: That’s right. Now, here in New York I know many, many people with many, many backgrounds and very often people who think that they – people who do know me as an individual – frequently reveal that they have no sense of the experience behind me – the extent of it and the complexity of it. What they have instead is good will and intellectuality.

RPW: That’s a human problem, of course, all the way. It can be special in a case like this I presume.

RE: It can be special because suddenly something comes up and you realize, well, my gosh, all of the pieces are not here. That is, I’ve won my individuality in relation to other individuals at the cost of that great part of me which is a part of a group experience.

RPW: I encounter the same thing, I suppose, in this way. I’ve been congratulated by a well meaning friend who I think was a good friend – means well, you see – suddenly say after years of friends – it’s so nice to meet a reconstructed Southerner or a liberal Southerner. This makes . I don’t feel reconstructed, you see. I don’t and put me together. my experience, and I don’t feel liberal. I feel logical, and I resent the word – I resent the word reconstructed. I must say that it’s been a kind of liability here, and I said this to a musical man in Louisiana a few weeks ago, and he reconstructed Southerner going over the country So it was and everything else.

RE: I remember recently and I were out in the middle west and a very friendly man, in fact, he was our host, and we were drinking and having a warm exchange, and at one part he asked my wife, well, how did you and Ralph become so poised?

RPW: reconstructed?

RE: The point of it was, he said, he had some abstract idea of how people from our background should think, but I said this, you have to remember we’re city people. I knew that he was from a farm. And he forgot. Well, their people just – they lose sight of how complicated human experience is and how you absorb it in many, many ways. When I waited tables, I couldn’t’ help but listening to conversations – I couldn’t help but observe people – I couldn’t help but make judgments as to their character – all waiters do. I had some sense of what was going on – new notions came to me just by standing around and serving a man a meal. You can say that this is not dignified, you can say that this does not have status and so on, but you can’t take away from me what I absorbed from them, and once I get it, it depends upon what I want to make of it.

RPW: Like Shakespeare.

RE: Yes, or like anybody.

RPW: More like what you make of Shakespeare.

RE: It’s like this notion of the culturally deprived child – one of those phrases which I don’t like – as I have taught white middle class children, young people, who are what I call culturally deprived – they are culturally deprived because they are not oriented within the society in such a way that they are prepared to deal with its problems.

RPW: It’s a different kind of cultural deprivation, isn’t it? And actually a more radical one.

RE: That’s right, but they don’t even realize – they don’t recognize that this is – that sometimes these people can be much more trouble than the child who lives in the slum and knows how to exist in the slum.

RPW: What this is is action – action of words and action of economics. The other person is missing something another way – it’s not their – it’s more mysterious, what’s happening to him – is that right?

RE: Yes, it’s quite mysterious, because he has everything but he can make nothing of it.

RPW: It’s twice as difficult to remedy because you can’t see how to remedy it.

RE: He can’t see how to remedy it and he doesn’t know to what extent he has given up his past. He thinks he has it, but every time you really talk with him seriously you discover that, well, it’s kind of floating out there, and the distance between the parent and the child – the parents might have it, they might have it in the old country, they might have it from the farm, and so on, but something happens with the young ones.

RPW: Do you think there’s a real crisis of values in the American middle class, then?

RE: I think so.

RPW: I agree with you. I think there is too.

RE: I think there’s a terrific crisis, and one of the events it’s testing – in fact, bringing the crisis on, is the necessity of dealing with this Negro freedom movement.

RPW: Now, put it this way – does this work two ways – there are those who can’t deal with it, only to withdraw from it, who can’t accept the necessity of dealing with it on realistic terms – this is North or South or West or anywhere – forget the Southern picture for this moment. The other one is there are those who move into it – I’m making a statement now but I mean it as a question – there are those who are into it because they – it is their personal salvation to find a cause to identify with something outside themselves, outside their – the flatness of their middle class American spiritual ghetto and find a reality there to gain a true romance over that. Now, there have been several people including Robert Moses in Mississippi said the resistance of Negroes there to white well wishers or even courageous fellow workers is very great – very great. One thing absorb arbitrarily in their Negro culture, Negro speech, Negro musical terms, Negro musical tastes, and move in and grab, as it were, the other man’s soul. There’s real resistance, he says, but he and try and get something for themselves out of it. This is – it’s particularly resented.

RE: Yes, it is, and it always has been, and what’s new about it is its being stated, it’s being articulated. Because it’s reductive. It’s the assumption that the characteristic expression can just be picked up without paying the dues for it.

RPW: Take an apple off the cart and running -

RE: That’s right, and you say, well, you know, it’s not like that. It isn’t possible. A friend of mine told a story of a young white salesman who came down to Tuskegee in the ‘50’s and he became friendly with some of the fellows who used to stand around on the block and talk and drank a little bit. And he found that this was a good way of liking the speech, and he ended up trying to become a part of it. And many of these were quite unsophisticated fellows but they were quite amused to see this form of naivety. It’s like Christopher Newman in James’ The American going over and trying to move into French society and finding this complexity of values and attitudes. But, to get back to the other point, Negroes have resented the appropriation of their character, their image, and so on for commercial purposes as well as by those people who as you say are seeking causes. And I’m sure that there must have been quite a lot of resentment among the Negroes who encountered certain abolitionists, because the tendency is to use the other person for your convenience.

RPW: It’s awful human, isn’t it?

RE: It is, it’s awful human

RPW: Of course, now this same question, as some of you say, I don’t care what your motives are if they’re useful to a cause. That’s one – that’s a practical approach.

RE: That’s very practical.

RPW: Another person of a – would diagnose this – a very subtle minded man would diagnose this resistance, you see, not merely as a jealousy of command post taken over by say a Harvard boy who is going to train a local boy. He isn’t seeking that post but it’s forced on him because it’s a training post. Now, resentment or jealousy, human as it is, but this deeper more thing. Of course that’s marginal and is explosion which settles down But the element is an indication, isn’t it, of the white middle class danger?

RE: I think that some of that comes into it. I think that it’s so difficult for white middle class people to understand that the time has passed where their values could be so easily imposed upon Negroes. This gets into the question of leadership in Negro civil rights organizations and so on. That is, they’ve had the long experience – and I can’t speak as an official of any of these organizations, but the experience certainly is of long duration, whereby you make allies with people to work toward goals. But when it begins to pinch them they say hold off. And there is a matter of sacrifice and the use of that phrase self-determination involved here, and considering the added pressure upon the Negro groups through automation, through the increase of school dropouts, through the lack of reading skills and so on, there is a desperation which we feel which others don’t have to feel.

RPW: That is, here in the midst of what has been an expanding economy you have a contracting economy for the unprepared situation having been more poorly and poorly prepared for the change than his white brothers have been. Is that the parallel that you wanted

RE: That’s the paradox – there’s the paradox. And then there’s the other thing – the assurance, the unrealistic assurance that you can – because you come from a certain background you are in a position to know more about what you’ve begun. Now, this is a paternalistic attitude which has not been earned, it’s not traditional, it’s nothing except an assumption of superiority.

RPW: You mean it’s not even with responsibility?

RE: It’s not with responsibility either. But you assume that you are in a position to be a spokesman and analyze it, and you never stop to discover, well, what is this that I’m trying to do. And it also doesn’t allow for something new which has come into the picture, a determination no longer to be the scapegoat, no longer to pay, to be sacrificed, to – the inadequacies of other Americans. We want to socialize this problem. Let’s all of us sacrifice a little bit.

RPW: Now, the sacrificing is not merely a conveniences and vanities but a – but what more?

RE: Well, if the cost in terms of character, in terms of courage and determination and self discovery, to bring Americans’ conduct in line with its professed ideals. This is a basic thing, to really act out the old American ideal which you make so much fuss about. Negroes are doing it and they are most American in that they are doing it. And others are going to have to do the same thing. Well, I say “have to” – I don’t mean that we’re in a position to force anything, except the exertion of -

RPW: Well, let’s say force – but force has been a manifestation.

RE: Yes – a matter of pressuring and keeping this country stirred up. Because we have to keep it stirred up.

RPW: What has historically proved that thing – not just in America but elsewhere – social change doesn’t happen automatically – something has to happen to make it

RE: Yes, it’s, well, Harold Rosenberg and his “Tradition of the New” has an essay on character and drama and character in terms of the law, and he makes the point that drama is not like life, but the interaction, the plot, the scenes and the characters, everything are organized and selected to express certain values of the author, and with the law, it is the act – for instance, the act of murder – which reorganizes, reshapes the whole character of the man. That is, the law views the murdered as a murderer, he is a man without previous history in that sense, unless -

RPW: The definition hinges on the act, is that it?

RE: On the act – that’s it. But this is not true in life, and it isn’t true in the larger sense of what’s happening to Negroes now. There was a dramatic section involved, but it was an act of law, a decision of the Supreme Court which made possible a broader ground for struggle.

RPW: Let me ask a question bearing on that, Ralph – how much change in the general climate has there been, not merely the crystallizing out of policies of resistance on the part of Negroes and principles of organization and fact – but how much general climate of opinion, you see, in the world – in America as a whole – the white man’s America is the Negro’s America - is it merely a matter of what has happened to the Negro to put his pressure on, or has there been a real change, say in a hundred years, in the climate and basic attitudes

RE: Yes, I think so. We can look at the popular images of Negroes – I think that’s changed. It’s changed, as Albert Murray said, it’s gotten so now if a man says well, let’s go to the limit, James, he’s going out to see a bunch of Negroes, and he’s going to our concert and he’s going – part of the time he’s going to just see some Negroes and hear some Negroes.

RPW: These facts make a difference of attitude in themselves.

RE: I think so. And the other thing – we don’t recognize to what extent the country has been organized and kept in balance by the images of popular culture, and I’m thinking of – well, to back to the minstrel show idea of the Negro which was so popular for a long time – this was entertainment, but the idea, taken away from the entertainment, had a lot to do with how Negroes were treated, and this becomes very ambiguous when you get a book like Uncle Tom’s Cabin, where for the right reasons many wrong conceptions of the humanity of Negroes were thrown into the public mind. That’s why Negroes dislike the idea of Uncle Tom – that’s a negative term for us. And the other thing that has changed -- well, remember The Birth of a Nation -- that idea, and all of those movies which followed, showing the bug-eyed Pullman porter and so on – well, that has gone out of it.

RPW: Something has happened there.

RE: Something has happened.

RPW: Now effect of Douglas and Plessey before 1954 – something happened. Now, this is a general climate of opinion – a general attitude toward society.

RE: Yes, I think so, and I think that much of this comes back into World War I, with the actual – and the desegregation of the army – that had a tremendous impact – that, and the rise of the dark nations.

RPW: As a general context.

RE: I was listening to Louie Lomax on television on Sunday night in New Haven, and he made a point which is made by Negroes all the time, he said, the guys who were shooting at me during the second world war can come over here and make it impossible for me to go into a building. He can go right past me, and yet he was accepted as the country’s enemy. And this sense of one’s predicament is inescapable for Negroes, and it becomes even more dramatic when African diplomats come in and be served in places where American Negroes cannot be.

RPW: Well, it’s clear to anyone with any imagination or even powers of observation what has happened to the Negroes in America. I would think what’s happened to the white people in America a change of spiritual climate. Partly as a result of course something has happened to the Negro – I don’t mean it has happened by itself - how much has happened that is there? Is there enough gain to stake something on it, do you think?

RE: One can only hope about these things. I think that we have such a resistance – such a resistance toward events – we’ve had the luxury of evading moral necessities from the Reconstruction on -

RPW: As Ben Williams said yesterday, to quote him again, as on the national conscience, General Grant was somewhat miscast.

RE: He certainly was. He was in no position to handle it, and much of the looseness which we suffered from can be dated back to that period. It just seems to follow that you have to learn how to be morally correct when you have so much when you have so much mobility, when you can postpone the moment of truth. But I think that as we have become the major power in the world, we are being disciplined in the experience of frustration, and the experience of being found inadequate. We’re being – we’re slowly learning that the wealth doesn’t do us any good, that that isn’t what is needed.

RPW: Now, we were saying about another topic – same topic – well, we were talking about the spiritual dangers in the American middle class – here’s a national danger which is isn’t it? Is that right? Either bankruptcy – or at least the danger of bankruptcy – and in a world situation – a danger there of the bankruptcy of power because intelligence, is that it?

RE: I think so. That makes sense. I think so, and I think that what happens, either in the instances where we must use force or where we should use force, we don’t know how to confront this, because we have – we’re compromised so damned much with events and with ourselves. We think we can slip out of certain things but I don’t think so. I don’t think a great nation can act that way. It’s rather amazing to see the – all of the prosperity, all of the possibilities of leisure, and still have a nation which is in a state of anxiety. Something is wrong there. Something there is wrong and it isn’t the presence of Negroes. It isn’t even the presence of the civil rights problem although this is an aspect of it.

RPW: It does flow into it. I could agree with you immediately that that is not the central fact - flow into an American national situation and aggravate it. But the other thing which would have happened anyway – it’s happened in other parts of the world where they have no Negroes.

RE: That’s right. Well, what does man do about having so much power? We have always been in the position of controlling our own appetites and deciding how far we should go – that is, the problem of Ahab as against Moby Dick, and we just – the sky’s the limit. The national values become so confused that you can’t even depend upon depend upon your writers for some sense of the realism of character. There has been so much self indulgence – much of it to be traced back to the fad of psychoanalysis – the concept of Mamman doesn’t exist for many, many people in this country.

RPW: The concept of syntax doesn’t either. And perhaps

RE: Perhaps. This is rather strange to watch. I believe that there is a basic strength in this country, but so much of it is being socked away and no one seems to be too much interested in it.

RPW: It’s sadly true, I think. Let me switch the topic, if you will. Let me read you a passage here from Dr. Kenneth Clark on Martin Luther King’s philosophy – this will lead us back to the whole question of the nature of violence and nonviolence in a situation like this – the social revolution. On the surface, King’s philosophy appears to have health and stability, while the Black Nationalists betray pathology and instability. A deeper analysis, however, would reveal that there is also an unrealistic if not pathological basis in King’s doctrine. The natural reaction to injustice, oppression and humiliation are bitterness and resentment. The form which such bitterness takes need not be overtly violent but the corrosion of human spirit seems inevitable. It would seem, therefore, that any demand that the victims of oppression be required to love those who oppress them places an additional and probably intolerable psychological burden upon them.

RE: Well, is a man who is missing the heroic side of this thing, and he reveals to what extent he isn’t a Southern Negro. Now, I think this – it might sound mystical, but I don’t feel it’s so because I think it’s being acted out – that there is a great deal of power – and Dostoyevsky has made us aware – in humility. In fact, Jesus Christ has made us aware. It could be terribly ambiguous and it can contain many, many contradictory forces. is not working out of yesterday nor the day before yesterday. He is working out of a long tradition which is reinforced with all the – by religion and a number of other things. The people who are involved have been conditioned to contain these contradictory elements.

RPW: Do you mean conditioned by their training or by their history?

RE: By their history – by their history – I mean, many of them couldn’t even spell out what I’m talking about – even the leaders.

RPW: And not just the nonviolent clinics?

RE: No – no – not that – I’m talking about the necessity of having to stay alive during periods where many, many Negroes were killed. We know what the violence – the history of the violence, but the personal courage was not even a factor in this. The individual personal courage had to be held in check, and he had to determine who he was involved with and at what point he wanted to sell his life. This is the – certainly has been part of my experience, where I had to decide I might go into – to take on and fight over this – this guy wants me to fight, he’s trying to make me fight, what do I have to gain? Am I going to let him determine my worth? – to me?

RPW: To let him determine your worth to you, is that it?

RE: By some small insignificant violence. Because one thing that Clark forgets is that Negroes learned about violence in a very good school, and they have known for a long, long time that they can take a lot of head whipping.

RPW: Let’s go back now to what you said a moment ago – you said he lacked the conception of the basic heroism.

RE: Yes – the basic heroism of – the person who must live within a society without recognition, without real status, but who is involved in its ideals and who is trying to make his way to that society and who, because of this predicament in the society and his position in it, learns more of the real problems, the real nature of that society, the real values of it. He might not be able to spell it out philosophically, but you know that this is the truth – I live the truth and you do not live the truth, because you are not taking this into consideration. This imposes upon that person the necessity of understanding the other man and giving up some of his revenge.

RPW: Of understanding himself, too.

RE: Of understanding himself too – yes. Understanding himself and understanding himself in relationship to the other man. This puts a big strain – yes, it puts a big strain upon the individual. Nevertheless, isn’t this what civilization is about? Isn’t this what we aim for at the highest? Isn’t this what tragedy has always taught us?

RPW: One or two people whom I have asked this question say, well, this reflects their Christian philosophy, as it does – that the Christian philosophy believes in the redemption of the natural man and now you’re saying something else – different and not necessarily contradictory – you are saying – this is not forgetting Christianity, it’s forgetting heroism – another kind of redemption.

RE: That’s right – you’re forgetting sacrifice, and the idea of sacrifice is very deeply inbred in Negroes. This is the thing – my mother always said I don’t know what’s going to happen to us if you young Negroes don’t do so-and-so-and-so. The command went out and it still goes out. You’re supposed to be somebody, and it’s in relationship to the group. This is part of the American Negro experience, and this also means that the idea of sacrifice is always right there. This is where Hannah Ernst* is way off in left base in her reflections on Little Rock. She has no conception of what goes on in the parents who send their kids through these lines. The kid is supposed to be able to go through the line – he’s a Negro, and he’s supposed to have mastered those tensions, and if he gets hurt then this is one more sacrifice.

RPW: This is the end of the first tape of the conversation with Ralph Ellison. Resume on Tape 2.

*”Ernst” is a typo from the original transcript and is actually a reference to Hannah Arendt.

CollapseCONVERSATION 2, TAPE 1 Searchable Text

Collapse[These digitized texts are based upon 1964 typed transcripts of Robert Penn Warren’s original interviews. Errors in the original transcripts have not been corrected. To ensure accuracy, researchers should consult the audio recordings available on this site.]

JUNE 17, 1964 TAPE #1

SERIES II

Mr. WARREN: This is Tape #1 of the second interview with Ralph Ellison, June 17 – proceed. You say that many Southerners have been imprisoned by the feeling of a necessity of loyalty – of a necessity of being Southern, and that is clearly true. Now, there’s a remark often made about Negroes, that they are frequently imprisoned, or the genus of the Negro is imprisoned in the race problem – in the focusing on the race problem. I am concerned with a kind of a parallelism here between these two things. Do you mind, if you have anything to say on that topic, exploring that a little bit?

Mr. ELLISON: Well, I think that the parallel is very much there – very much a reality – that on the one hand the – well, let’s put it this way – just looking at it as a sort of legend, and this comes to mind because I am right in the process of reading Calvin Trilling’s piece on the Mardi Gras in New Orleans, where he’s done a piece really on the Zulu king, and you get this process going on, and now there’s a – well, since 1961 there’s been a great confusion in the Negro community over whether the Mardi Gras Zulu – King Zulu – should continue. Now, we know that there is an area in Southern experience where whites and Negroes achieve a sort of human communication, and even social intercourse, which is not always possible or always present in the North. I mean, that’s the human side. But at certain moments a reality which is political and social and ideological and so on asserts itself, and so the human relationship breaks up and people fall into these abstract roles. That’s a great loss of human energy goes into maintaining our executive roles. In fact, much of the imaginative energy – much of the psychic energy of the South among both whites and blacks I think has gone into this particular negative art form, if I may speak of it that way.

RPW: Just the strain of maintaining this stance?

RE: I think so. I think that – because in the end, when the barriers are down, there are human assertions to be made, there are – in terms of one’s own taste and one’s own affirmations of one’s own self, one’s own way of life, and this is a big problem for Negroes. There is much about Negro life which Negroes like, just as we like certain kinds of Negro food. The dieticians might not care for it, but it satisfies our taste and it fulfills all of the other overtones, all of the references, all of the – well, let’s put it this way, it expresses a culture and it expresses us, and that’s good enough. And one of our problems now is going to be to affirm those things when there is no longer any pressure there saying, well, all right, you’re no longer kept within a Jim Crow community, what are you going to do about this? Do you think that there is some form of life which is more enrichening [enriching], do you think that there is going to be a way of enjoying yourself which is absolutely better than this, you see. It’s a matter of finding a human core after the fighting has stopped. And I think that this holds for whites, it certainly shows up in the white Southerners, the mountain people who turn up in Chicago. They have a real problem there. They feel they are alienated, their customs and mores are in conflict with those of the big city just as ours were and still are as we come to the North, and the problem is to affirm and finally to affirm without being contentious about it.

RPW: To affirm in a simply pluralistic society, without -

RE: Yes, without any value judgments being negative or positive being placed upon it. I watch other people enjoying themselves, I watch their customs and I think it one of my great privileges as an American, as a human being living in this particular time in the world’s history to be able to project myself into various backgrounds, into various patterns, not because I want to cease being a Negro, not because I think that these are automatically ways of conducting oneself or extending oneself, but because it is a privilege, it’s one of the great glories of being an American. You can be somebody else while still being yourself. And one of the advantages of being a Negro if we’ll ever recognize it, is that we can do this, and we have always done it. We have always had the freedom to choose or to select, to reject and to affirm that which we have taken from any and everybody.

RPW: In a paradoxical way it’s a bit more fluid than anyone else – the situation of anyone else in the -

RE: That’s right. It’s been more fluid and we had no particular investments, once we left the Negro community and being snobbish behind. You know, we say, well – it’s like Louis Armstrong when he talks about teaching somebody to play jazz. I think he’s talking about teaching a few things when they were on the river boats, - these two young men. Well, he was speaking very much as jazz musicians spoke when I was a kid. They were delighted when anyone liked the way they played music. I mean, that was the point. You like this, this is a celebration of something we feel, you feel it, well, all right, we’re all here together. And I think that this has been basic to the Negro situation, and it isn’t recognized by sociologists and by journalists who consider that Negroes have no choice. If anything within the world beyond the restrictions of social movement and political movement and economic opportunity, we probably have more freedom than anybody.

RPW: This would relate – or would it? – to the – some concept of the Negro’s position as primarily existential in a world where – where this applies to lessons we other Americans say.

RE: Yes. Well, I think that this is a basic -

RPW: A purer existence.

RE: Yes. And this is a basic American situation. It depends upon what you want to take, how you want to use your life, and what assertions you want to make. Well, with us, we had this blocked out area in which we could live on a social level and a political and an economic level -

RPW: Here is a matter of just a tactical concern. I know some people Ralph, white people or Negroes, who would say to what you are saying that this is the current apology for a segregated society. Of course it’s not. I know that. I know it’s not. Who would say that it is – it works that way. Just as you’re saying – some Negroes say the challenge of segregation made me develop whatever force I have, and are called immediately apologists for segregation. How do you answer such a charge? How would you answer such a charge?

RE: Well, there’s no answer to such a charge beyond this, is that if I am -

RPW: If a damned fool is a damned fool you can’t change him.

RE: You can’t change him. If one thinks that by asserting reality that is, - which is another way of saying, asserting my humanity – by recognizing what my life is like, by recognizing what my possibilities are like, and by the way I’m not for one minute pretending that the restrictions of Negro life do not exist, but I’m on the other hand trying to talk about how Negroes have achieved a very rich humanity under these conditions. Now, if I can’t recognize this or if recognizing this makes me an Uncle Tom, then Heaven help all of us. I know, in the first place, that there has been the necessity for Negroes to find other ways of asserting their humanity than in terms of political or military force. I mean, this – we were outnumbered, we still are, and this did not cow us as a lot of people like to pretend. It imposed a discipline upon us and we see that discipline now bearing fruit in the Freedom Marches and so on, and the willingness of little children and old ladies to take chances, that is, to walk up against violence. This is an expression not of people who are suddenly freed of something, but people who have been free all along.

RPW: How do you relate this, Ralph, either positively or negatively to the notion that the Negro movement of our time – is a discovery of identity?

RE: I don’t think it’s a discovery of identity. I think it’s an assertion of identity. And it’s an assertion of a pluralistic identity. The assertion in political terms is that of the old American tradition. In terms of identity it’s revealing the identity of people who have been here for a hell of a long time.

RPW: You know the line, of course, that you find the extreme expression in Black Muslimism – just, you know, along that line – about I’ll teach you who you are and therefore you become – for the first time yourself and become real. And the same line is followed by many psychological curlicues and elsewhere. And I was just trying to get your statement about this continuity as related to that notion.

RE: Well, my notion of the American Negro life is that it has developed beyond any restrictions imposed upon it, historically, politically, socially, economically, because human life cannot be reduced to these factors, no matter how much these factors can be used to organize action, to prevent action. That’s something else. But Negroes have been Americans since before there was a United States, and if we’re going to talk at all about what we are, this has to be recognized, and if we’re going to say this, then the identity of Negroes is bound up intricately, irrevocably, with the identities of white Americans, and this is especially true in the South.

RPW: It is, indeed.

RE: There’s no Southerner who hasn’t been touched by the presence of Negroes. There’s no Negro who hasn’t been touched by the presence of white Southerners. And of course this extends beyond. It gets – the moment you start touching culture you touch music, you touch popular culture, you touch movies, you touch the whole damned structure, and the Negro is right in there helping to shape it.

RPW: Now, what about another notion that’s sometimes in this connection, that the tradition of slavery and the disorganized quality of much Negro life after Emancipation, meant the loss of role or the man. Patriarchy was the rule, or at least more than the ordinary man, you know, bossed family. How does your line of thought relate to that so-called fact anyway?

RE: Well, I’m willing to recognize or to agree with the findings of the sociologists, the historians, that the Negro woman has been a very very strong force in the Negro family. I’m also willing to say that the disorganizing effects of the – well, of slavery, and of the lack of opportunities for the Negro male has made for a modification of the Negro family structure – I mean, of the – yes, of the family structure. But I am not willing to go as far as the sociologists go, who would set up a rigid norm, you see, for the Negro family or for the – usually what they’re talking about – white Protestant family – and say that this is the only type of family which is positive. I know that some of the most tyrannical heads of families are Negro men. I also know that some of the most patriarchal and benign heads of families are Negro men. This too is true, you know. I guess I’m one of the few – let’s see, my father’s father was a – but my father’s father was a slave.

RPW: That close?

RE: That close, you see. Now, what are they talking about? My grandfather, Alfred Ellison, was known as a stern father. He was a man who was respected in South Carolina, and I guess if the old-timers are still there, black or white, they will talk about Uncle Alfred because he was a man of character who had insisted upon certain things. In fact, he insisted so hard that my father ran off when he was a teenager to join the American army. On the other hand, now, my father died when I was three years old, and my mother stood in for us. Now, I was never made to feel neglected. I felt sometimes ashamed that we didn’t have a father, but I knew my father, I knew him very well. But my mother sacrificed and worked to keep the unit to the family. That is, part of the strength which she had gotten and she did not come out of a broken family. She knew her father. She was part of a big family with a Negro man at the head of it. So so much of this seems to be abstracted from the continuity of life when you put it in a historical perspective.

RPW: It’s hard to know what the statistics would be – I have observed in a very limited way what it’s worth – that time after time in talking with, well, Negroes I’ve interviewed in this series of things, that a very strong reference to a father or a father-presence is in these cases of people who have a strong personality, a strong driving personality.

RE: Yes. Well, that is true, I admit. The other things to be said – and this is the other side of the disorganization which did exist – but you always had this – all these guys who were around – not guys – these were men- these were respectable men in the community – who always went to – at least went through the ritual of being concerned for the orphans and the widow women. And these women had a special status. They did try to look out for them. Some of these were uneducated men, some of them were professionals, but that too was a part of least of Oklahoma City, the Negro community there. The first two boys who were signed up to go on the encampment, the first encampment that the Negro community got together for the boys, were Herbert and Ralph Ellison, my little brother and me, because they were doing this for the community, and they looked out for those people who -

RPW: Because you were orphans?

RE: We were orphaned. I mean, that was the idea. And they respected my father, they knew what he was like, and they knew what my mother was like. Now, I’m willing – make a little leap here – all of this talk about the dominance of the Negro woman – and the Negro woman can be awfully strong – there’s no doubt about this. She had to be, given the circumstances. But when you look at the rise in importance of the white woman – I’m not going to talk about the Jewish family, which is very often matriarchal – the German immigrant family, which again is often matriarchal – the Italian family, which you know even in Rome, no matter how the father is there, how much his presence, that old lady is the one who is asserting a hell of a lot of power – now, in the United States, we talk about the rise of the importance of women in financial organizations, they own more stocks, they do more this, that and the other – they have been behind many of the important reform movements and so on – this just brings the circle around as far as I’m concerned. Maybe it’s a male conceit that the man has a force within the family which dominates – in the white family, which dominates that of the woman. I doubt this very seriously.

RPW: I think you’re right. Let me cut into some matters of American history, some American figures for a moment. Could you give a – sort of a character sketch, an estimate of, say, Thomas Jefferson?

RE: Well, Thomas Jefferson was a most sophisticated man of his times, an idealist given over to, I guess, a great concern with human possibility, drawing upon all the thought of European political philosophers who set out with his colleagues to build a better way of life in this country. He was limited by the realities of his time, by the system of government and the necessities of production, which included slaves, and a number of other things. He was a politician. We tend to forget this too about him.

RPW: If he hadn’t been he would have been in another line of work.

RE: He would have been in another line of work, and it’s part of the fate of the politician to be involved – very deeply involved in moral compromise. There’s a lot being said about Jefferson’s theories of Negro humanity and so on -

RPW: That’s one of the things I’m getting at – how that – what weight you give to that or what perspective do you put it in?

RE: Well, I put it in the perspective of history, of human history, and exactly that. I don’t care whether he liked Negroes or not – I mean, that isn’t important. What is important, it seems to me, is that he helped set up the Constitution. Now, as long as I have the Constitution I have the possibility of asserting myself and not depending upon any paternalistic ideas which Jefferson might have held or might not have held. You cannot demand too much of any human being. He moves out of his own historical circumstances, he moves in terms of his own personal life, he moves out of a complex of motives and ideals and frustrations and cowardices and heroisms which is faced by anyone who is lucky enough to get in a position of making important policy. But one thing is certain. His concept of human possibility was broad – in fact, it was noble. If he couldn’t quite see some of my own people mixed in this, included in this, that’s too bad. But the fact of it is that his efforts – and I think I’ll probably live to see the day when the University of Virginia will be an instrument – an institution which help extend the possibility of Negroes within Virginia. All you can ask is that a man do what he sees to be done as well as he can. I think that Jefferson did this.

RPW: Let’s switch to another kind of character – John Brown. How do you read him, Ralph, as – psychologically and ethically and historically?

RE: Well, I think that John Brown was demonic – I prefer to use that term than to call him a lunatic – you know, he was popular and still is among certain people. I rather like the idea of Brown which turns up in Faulkner’s The Bear, a man who was utterly impractical and perhaps was a little off his beam. But he was dedicated to a certain ideal and tried to put it into operation, and thereupon showed himself up to be a most unpolitical man. He had absolutely no idea of how to make a revolution and completely misread the nature of slavery as far as the slave sense of timing and the slave’s sense of what was possible at the time. I think that there is a certain grandeur about him in terms of his willingness to pay the price for what he believed in, and I think there’s a certain nobility about his last speech.

RPW: His whole demeanor in the last phase is extraordinary. How it becomes that is a story that nobody knows, but it is extraordinary.

RE: I wonder about this. Was he always that eloquent?

RPW: No - no. What about Lee? How do you read him?

RE: I read him, again, as a man who was caught within the contradictions of a system in which he was born and loyal to people among whom he grew up and who somehow – and this is difficult for me, although I tend to understand it – but – well, let’s put it this way – regionalism – I’ll use that term – always puzzles me when it goes beyond – at least when it asserts values which it considers as primary to those of the country at large. And I’m phrasing that very badly -

RPW: I don’t think so. I mean, it’s perfectly clear. And it’s a question of how much history you put into this, I suppose. I mean, what Virginia could mean now and Virginia could mean then appear to be very different things.

RE: From what it would mean now. I can understand, nevertheless, that the – the contradiction.

RPW: End of Tape #1 on June 17 with Ralph Ellison. Proceed. (end of tape)

CollapseCONVERSATION 2, TAPE 2 Searchable Text

Collapse[These digitized texts are based upon 1964 typed transcripts of Robert Penn Warren’s original interviews. Errors in the original transcripts have not been corrected. To ensure accuracy, researchers should consult the audio recordings available on this site.]

ROBERT PENN WARREN RALPH ELLISON SERIES II, TAPE #2

There was no recording of interview on this tape. The testing at the beginning registered, and the voice of RPW announcing the end of the interview – but the tape between was blank.

Collapse