Hastie considers the revolutionary nature of the civil rights movement, and he conjectures that reports that African Americans wish for white liberals to stop participating in the civil rights movement have been exaggerated. Hastie opines that, in the civil rights movement, issues of race and class intersect, and he discusses the extent to which a solution to racial strife in the United States requires addressing socioeconomic issues. Hastie discusses New York City school integration and busing. Asked to consider Gunnar Myrdal's hypothesis concerning a plan for Reconstruction that would have worked, Hastie offers his belief that Reconstruction might have proven much more successful had the federal government continued its commitment to the freedmen for another 10 years. Hastie contends that, once a civil rights law is passed and desegregation is complete, the task remaining to all men is to adopt a worldview in which race is of no consequence. Hastie considers the past and present relevance of W. E. B. Du Bois's "talented tenth" and Booker T. Washington's ideas concerning labor, and he discusses sectional differences in the pace of the civil rights movement. Hastie concludes by discussing programs that give preferential treatment to African Americans, paying specific attention to preferential hiring programs.

Notes:

Audio Note: Tape 2 cuts off a few words short; however, the transcript is complete. The pitch of the voices varies at times but does not affect intelligibility; as Warren says at one point, it's not as if they're singing. There is a brief interruption in the middle of the second file, and an obvious conversational gap (possibly small) between the second and the third files.

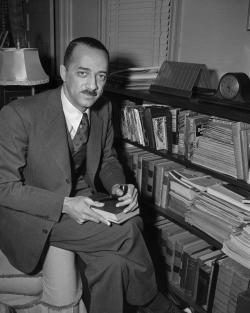

Image: Original caption: William H. Hastie, Governor of the Virgin Islands, was nominated by President Truman to the Third Circuit Court of Appeals, October 15th. Hastie, a former U.S. District Court Judge, is the first Negro to be named to a circuit post. October 15, 1949. Copyright: Bettmann/Corbis.

Audio courtesy of the University of Kentucky.

William Hastie

William H. Hastie (1904-1976) was an attorney, politician, and federal judge. A native of Knoxville, Tennessee, Hastie received an undergraduate degree at Amherst College in 1925, followed by degrees (an LL.B. and S.J.D.) in law from Harvard Law School in 1930 and 1933. After graduation Hastie was appointed an assistant solicitor in the United States Department of the Interior, where he advised the department on racial matters. In 1937 President Franklin Roosevelt appointed Hastie to serve as a federal district judge in the Virgin Islands. He left the Virgin Islands in 1939 to become the dean of Howard University School of Law, where he served until 1946. During World War II, Hastie also served as a civilian aide to Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, but he resigned to protest the discriminatory practices of the United States armed forces. Hastie was elected Territorial Governor of the Virgin Islands in 1946. He served as Governor until 1949, when President Harry S. Truman appointed Hastie to serve as a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. It was the highest judicial position an African American had attained at the time. Hastie served on the Court until his death, and he served as Chief Judge of the Court from 1968 to 1971.

Image: Original caption: William H. Hastie, Governor of the Virgin Islands, was nominated by President Truman to the Third Circuit Court of Appeals, October 15th. Hastie, a former U.S. District Court Judge, is the first Negro to be named to a circuit post. October 15, 1949. Copyright: Bettmann/Corbis.

Transcript

TAPE 1 Searchable Text

Collapse[These digitized texts are based upon 1964 typed transcripts of Robert Penn Warren’s original interviews. Errors in the original transcripts have not been corrected. To ensure accuracy, researchers should consult the audio recordings available on this site.]

TAPE 1

JUDGE HASTIE

This is Tape 1, of a conversation with Judge Hastie, in Philadelphia, April 20.

[00:00:24] Q: Judge Hastie, in what sense do you think we could call the Movement, the Negro Movement, the Negro Civil Rights Movement, the Civil Rights Movement, however we choose to call it – a revolution. In what sense is it a revolution? Or is it one?

HASTIE: It's a revolution in the sense that it is a movement for more rapid social change, than will take place in the normal course of events. Actually, the drive, if I may so describe it, for the modifications or correction of our basic law, and for equality of status and rights under law, the drive in organized form, goes back to the early 1930s, to about 1930 roughly. And it has continued with some organization ever since. The first 15 years the pace of change was slow. And is the acceleration in the last 10 years, the, probably the fact that more Negroes, and whites as well than ever before have openly and aggressively identified themselves with the request – yes, demand - for change, that has caused the continuity of the effort in the last ten years, to be described as revolution. But I suppose my real point now is, that, call it what one will, it's a continuation and an acceleration of a drive, with a greater accession of strength through aggressiveness of the participants and through a wider participation, but nonetheless, a continuation and acceleration, rather than a new departure.

[00:03:07] Q: Dr. Aaron Henry, of Clarksdale, Mississippi, who is president of the N.A.A.C.P., there, referred this long process in this way. He said to me, the N.A.A.C.P. and all the other individuals and agencies who have worked to define the legal basis that has been in education and other departments of life, have made possible, to have a revolution within the terms of law. But now the attack is on laws that are not laws, and practices that are not legal, because now a citizen knows what the law actually means to him. Am I making myself clear.

HASTIE: Yes, you are. Part of the problem is the obvious continuing problem of definition of the meaning of words. Now one can define revolution as an effort to bring about change inconsistent with the basic legal order, and of course, there are persons in this day and time, who urge that. But I think that the gentleman who you are quoting, is using revolution as perhaps most people do in this connection, to mean a rapid change, brought about through a great deal of popular or community pressure, within the national constitutional framework, and within the laws of the United States, and the laws of the states that are permissible under our constitution. In that sense many would say change thus accomplished is not a revolution, but I don't think the word by which we call it, makes a great deal of difference.

[00:05:20] Q: He said, to continue just for a moment, that this is a movement toward legality, rather than from legality.

HASTIE: I think that's true, because I think what he means is that the political concept which is fundamental in our nation, and its basic law, is a concept of an equalitarian society. And if all valid law has to respect that concept, then the movement is to bring both our practices and certain of our local statutory enactments, within the ideological framework, indeed, within the constitutional framework, of the nation. So in that respect I would agree with him entirely.

[00:06:27] Q: There's another aspect of not merely a revolution, but I suppose any strongly felt popular movement – a revolution, say, lives on hope and hate, two great motivating elements – emotional charge. Hope is clear in this. But hate has a part in it. And the hope and hate direct themselves at liquidation of some regime or some class, historically speaking. The problem then, is can you keep this kind of motivation, that hate part of it, which we have to recognize as a component, constructive, when you're actually moving to maintain a society, and not to liquidate it.

HASTIE: Well – I think, to say, "to keep the hate part constructive", is almost contradiction.

[00:07:33] Q: Yes.

HASTIE: It assumes that hate is a constructive force, when the emotion of hate drives people to tear and rend whatever is the object of the hate. But the movement remains constructive so long as hate is depersonalized. I suppose this is really a translation of the Christian ethic, you hate the evil in man without hating man himself, retain a certain amount of compassion for the individual. Now, I suppose that's not the type of hate that many people are talking about in this connection. But I think, to a considerable degree, it has been possible to maintain drive with that kind of hate, as distinguished from so much of the personalized hate of individuals, and to a considerable extent, because most Negroes do not have the feeling that they are deserted by the entire white community. The, perhaps on a very narrow local scene, that sometimes is the case. But I think most Negroes have maintained throughout this, a sense that there is a very large element, a very powerful element, in the national community, and in most local communities, that gives some significant support to the so-called revolution.

To digress a minute on that, some people have expressed shock in the last few weeks, that 25% of the vote in the Wisconsin primary election, went for the Governor of Alabama. I think that involves a presupposition that there is an overwhelming popular support in Wisconsin at any rate, for the accomplishment of the revolution. Personally, I don't think the support is as overwhelming as we would sometimes hope it was and I would suspect that 25% of the citizens in Wisconsin, look at least askance at the revolution. In that sense it may not be an inaccurate representation of public opinion. But I cite that not to point to the 25%, but really to the 75% and emphasize that there is an awareness and a sense of a great support of rapid change in this area in the white community.

[00:11:07] Q: On the matter of the role of the white sympathizer, or white liberal, or whatever he is, we find a very strongly articulate impulse among some Negro groups anyway, to say – liberal, go home. White man, go home. For instance, James Baldwin the liberal an – affliction. Or we find others saying – you've served your time. Now we are through with you. Now we take over. Take the white walled tires off the front wheels of the car. You know, all this impulse. How do you read this impulse, the thing behind its impulse, and it, as, not a psychological fact, but a political fact? How do you set its value.

HASTIE: First of all, I'm a poor person to judge, because of the fact that I have not been in position to be out in the hustings, and to personally sample grass roots reaction, and get a sense of the feel of great numbers of people. I, and there’s also the imponderable, as to the relative importance of leadership view, and whether there is a mass reaction and view distinct from what Baldwin or any other individual or group of leaders may say. So with that preamble, I just hazard one or two really guesses.

I think the amount of hatred of everything white, and rejection of white liberal assistance, is probably exaggerated. Maybe the wish is father to the thought. It is sensational and therefore it makes newspaper headlines, when a Negro takes this position. Perhaps because of our generations-old stereotype of the Negro as a very docile sort of person. But my guess is that at least as of now, there is not as much rejection of the support of whites, as some of the headlined utterances might cause one to believe. Take the March on Washington. It was a prime indication of what happens when the chips are down, and it's necessary and desirable to get as wide based support as possible. So recognizing that this is the reaction with which your question started, is a fact, is experienced by numbers of people in leadership position, and of course, numbers of followers, my own guess and it’s hardly more than a guess is that as of now, it’s not as great as we sometimes think. Certainly it has a potential of getting greater, and that I think, is the importance of the drive for civil rights legislation now for many other changes quickly, if only to prevent the further development and spread of this very dangerous potentially catastrophic point of view.

[00:15:34] Q: Within the revolution itself, there is no clearly defined leadership now. Historically, looking back on great social movements, even those that don't emerge as full fledged revolutions, there is usually a concentration of leadership before it's over. Do you see any tendency toward such a concentration for the centralizing of authority and prestige, in this, the Negro Revolt, or the Negro Revolution, or whatever we choose to call it.

HASTIE: Again, I doubt whether I can give a very meaningful answer. Certainly, as you know, the leaders of five or six of the most important national civil libertarian and Negro advancement organizations, has been meeting informally, attempting to reach common ground for several years. And again, turning to the March on Washington, that indicated the potentiality and also the willingness of leadership of those organizations, at any rate, to work as a group. Now, it's true, it’s a group without any titular head, or any one person who's recognized as the dominant force. But though revolutions of some types have certainly moved when there was this sort of single dominating personality in a group, I’m not sure whether this is ________ generous enough to go forward without that, but I agree with you that certainly there has not emerged that type of unitary leaderships.

[00:17:40] Q: There are some aspirants right now apparently, who are emerging. It's, a character such as Malcolm X, presumably he can only thrive in that role, and there are other characters of that cut, who are beginning to appear on the scene. How much of a problem do you think there is to contain this impulse toward personalized, centralized over-reaching authority? That offers more emotional excitement than the old line organizations, is that a real hazard, do you think?

HASTIE: Again, I don’t know, unquestionably, in local communities and local situations, for the time being, such leadership will gain dominance, and at times and places, in the last two or three years, has become dominant. But it is leadership that appeals to the hopeless, to those who are convinced that there is no, there is no satisfaction, no solution, to be found within the present order, under leadership of the sort that we have experienced in the past. And I'm far from sure that that sort of hopelessness is characteristic of the overwhelming number of Negroes in America. So I could only hazard the view that the success of that kind of leadership will be in direct proportion to the hopelessness or desperation of the potential followers.

[00:19:57] Q: It is said by some observers, that the split now between the rising upper half of the Negro population, who are responsible citizens, the professions opening to them, jobs opening, businesses opening to them, and the submerged third to one half, creates a problem, that is the split within the situation of the Negro citizenry, that makes the problem. That half, say, or more than half, whatever percentage we take, does have a sudden opening of opportunity. The other half feels more desperate than ever because they are cut off from this, which their own even blood relatives have frequently, much less, members of the same ethnic group. This is hidden dynamite in the situation, does that make sense.

HASTIE: I think it does, and this is what, part of what we've been saying. The appeal of Malcolm X is, basically is to the most disadvantaged group who have this feeling of hopelessness and desperation. That's why, of course, the various economic and social measures undertaken both locally and nationally to benefit persons regardless of race, or in that economic and social situation, those measures of the greatest importance and value arresting the destructive type of racist revolution that the Malcolm X's would seek to foment.

[00:22:05] Q: In other words, we have here the intersection of an economic class problem and a race problem at the same time.

HASTIE: There's no question about it. Many people have said that from a point of view of social strategy, if the people who wanted to keep the mass of Negroes, as the expression goes, in their place, had realized it, the best way to have done it, would have been a generation or two ago, to encourage and advance a Negro elite, and identify them with the white community. Certainly the fact that all Negroes, at least up to a generation or two ago, felt themselves in essentially the same boat, gave a measure of solidarity, provided a leadership among the better prepared and trained Negroes that conceivably might have been, not have been present, had those people not had the same sense of suffering, that some of them, don’t have today.

On the other hand, let me say this. We must remember that among young people, colored as well as white, our college trained people are people who have had advantages and opportunities, are, many of those are in the very forefront of the struggle now, and concede it as a humanitarian cause to which they dedicate themselves, so I think that’s about all I can say now on that subject.

[00:24:03] Q: The tendency to isolate the race question from the surrounding questions, if I call you right, create a certain unreality in the possibility of solution, does that follow? To isolate the race question from the context in economic.

HASTIE: Oh, oh, surely, I don't believe any serious thinker about this matter, believes that the racial question can be dealt with apart from the whole socioeconomic complex of American life. And certainly all of the constructive efforts to deal with it, involve a combination of approaches recognizing the problem as being more than racial.

[00:25:04] Q: Let us take a case such as the Harlem schools and integration of Harlem schools. Given the population ratios, and the area to be covered in New York City, we have a test tube case of integration by bussing, as a solution aimed at the racial aspects. Other aspects we know about. Can you see a solution in terms of bussing as significant.

HASTIE: Again, I don't know. I'm unable as of now to satisfactorily answer for myself several fundamental questions, again, which are not essentially racial, which underly the solution to the racial problem. First, is the very localized neighborhood public school, a sound concept, without regard to race, for an urban area, characterized by concentrated slums, concentrated middle income groups, concentrated areas of privileged living. Do we, should we reexamine, and if we reexamine, with what results, should we reexamine our whole premise of the soundness of the neighborhood school. In asking that, does the neighborhood school have an advantage in the, in having the opportunity to concentrate upon the undoubted special requirements of underprivileged children. Is the, is our basic shortcoming that we have failed to do that, as distinguished from failing to mingle students in all socioeconomic classes, in the same, the classroom. My difficulty, and I suppose certainly it's a difficulty of most people who try to think through this, is what is the really most advantageous thing for the development of the youngsters. And of course, weighed with that, has got to be the disadvantage of the youngster feeling that racially or culturally he isolated from the rest of society, and with all of the things that that sense of isolation to him. So, I really, after using many words, have to confess, I can't come up with an answer to your question.

[00:28:29] Q: I was thinking of something like this. Suppose we admit integration is a great good, offers variety of experience, it offers some curative or preventive force such as isolation of any, either the white man or the black man. It does those things. But take Washington. Take some city like that, becoming an all Negro city. How can you integrate, where are the white children coming from?

HASTIE: You're saying, if the ghetto begins big enough, there's nothing but ghetto to integrate, that's entirely true, and forces us in situations of that sort, of necessity to seek a different type of solution.

[00:29:28] Q: A person who is normally very responsible, and maybe responsible in this, said to me, in that case – bring them from Virginia. The pupils to integrate. That does create some legal difficulties, I suppose. But I wouldn't try to ________ you about those. But it's the state of mind I'm talking about there. Think that this is the primary item, rather than evaluating in a context of other goods.

HASTIE: Well, it certainly does have to be evaluated in the context of other goods. Of course, now we are, we get to the again, to the nature of revolution. People do not get stirred up over a complicated group of ideas, some cutting one way, some cutting another. As we’re sitting here, discussing pro and con. People get stirred up when they adopt and struggle for a simple, very simple concept; in areas of Africa of course, you use one word – the Swahili word for freedom – Huhuru. And you rally around people around the enthusiasm generated by that concept. Revolution always oversimplifies ideas. And of course, one of the great problems of leadership is that though ideas be oversimplified in the minds of many people, that leadership with more sophisticated thinking attempts to adjust itself and its programs to the total need, viewed in a sophisticated way.

[00:31:42] Q: I'm not trying to put words in your mouth, now, but I'm trying to paraphrase. By this line of thinking, then, it's conceivable that a thing like bussing, or integration serves as a symbol for many other things, and it is not treated only in the direction of this special good in a complex of goods; becomes an overriding symbol which appeals generally, can be used as a cry.

HASTIE: I think that's a fair statement. Though I supposed in a place like New York, it is an expression of dissatisfactions with many aspects of the local public schools, which may not be racial in themselves.

[00:32:37] Q: Just damn bad schools.

HASTIE: And of course, it may be much more, it may reflect the dissatisfaction with slum living, in that it means getting the children outside of the slum at least for two or three hours of the school. I'm not sure what the psychology of it is.

[00:33:03] Q: You have too, though, a counterpoise of middle class, upper class, Negro families, sending their children to private schools, further depressing the "ghetto schools".

HASTIE: That's true, of course, again, you have considerations and impulses that are not racial – motivating people who are identified with the racial struggle.

END OF TAPE 1

Collapse

TAPE 2 Searchable Text

Collapse[These digitized texts are based upon 1964 typed transcripts of Robert Penn Warren’s original interviews. Errors in the original transcripts have not been corrected. To ensure accuracy, researchers should consult the audio recordings available on this site.]

TAPE 2

[00:00:16] Q: Let me read you a quotation, Judge Hastie, from Dr. Kenneth Clark about Martin Luther King's philosophy. "On the surface King's philosophy appears to reflect health and stability, while the black nationalists betray pathology and instability. A deeper analysis however, might reveal that there is also an unrealistic if not pathological basis in King's doctrine. The natural reaction to injustice, oppression and humiliation, is bitterness and resentment. The form that such bitterness takes need not be overtly violent, but the corrosion of spirit, seem inevitable. It would see, therefore, that any demands that the victims of oppression be required to love those who oppress them, places an additional and probably intolerable psychological burden upon the victims."

HASTIE: Well, the answer to that, of course, is an answer that the psychologist has to give, and I'm not a psychologist. As you were reading I was thinking that the model for Dr. King of course, was Ghandi. And we are essentially a pragmatic people in this country, I would suggest that the answer might be sought in the experience of other people who had practice such an approach. Of course, looking at this comparison, we know that it was not all perhaps a relative few of the people of India, who thoroughly accepted Ghandi's counsel of nonviolence. Indeed, the epoch of Ghandi in India, saw a tremendous amount of violence. I would suspect that many people, rather than having their personalities bruised by an unnatural acceptance of nonviolence, just reject it when it goes too much against the natural human reaction, and so instead of being bruised, they bruise the adversary despite all the admonition of the Ghandi-like leadership.

I, other than that, I’m not sure what I would say about Dr. Clark’s comment.

[00:03:53] Q: Of course, Dr. King says Dr. Clark does not understand him.

HASTIE: Dr. Clark what?

[00:03:58] Q: Does not understand him.

HASTIE: Oh, well, I don't know what Dr. King means when he says Dr. Clark doesn't understand him.

[00:04:07] Q: Dr. Clark hasn't read me.

HASTIE: King, of course, is philosophically assuming a goodness of the human spirit, I suppose, which Clark is denying. And that goes to the fundamental concept of man's nature, which was not solved before the present revolution, it will certainly not be solved during it.

[00:04:45] Q: There is also the tactical nonviolence which says, as Dr. Abernathy put it in a conversation, it's right, nonviolence is right, but also the white folks have more guns.

HASTIE: Well, of course, when the spirit gets bruised enough, people forget who has most, more guns, and people charge into the mouth of guns. But certainly in sober and more thoughtful moments, the recognition of where the heavy artillery motivates human conduct.

[00:05:33] Q: There's one line of thought that I've encountered, that says nonviolence used aggressively, is inherent in the history of the Negro in America. This is merely continuing a natural impulse, a natural situation, there are all sorts of things, the plantation slowdown; the joke, the yassah-ing somebody to death; all of these things belong to the technique of nonviolent aggression. Now to philosophize this, if this philosophizes three centuries of expertise in the matter.

HASTIE: Well, there's something to that. This three centuries of expertise is, has been of course, a necessity of survival. When people are in slavery or when they are in a subjugated condition, which is not formally slavery, survival requires that limited type of nonviolent aggression. But the difference is that King is preaching that even in situations where for the moment, some gain might follow from violent assertion, that the human spirit should be so disciplined, that it would reject that. But I'm not sure too much what is gained by rationalizing this, as a continuation of the survival tactics of any subjugated minority. But I think historically there’s truth in it.

[00:07:57] Q: I don't know what is gained that way either. I report this, I've encountered it several times, and I hadn't thought about it in this light, until someone offered this to me. It's always struck me as strange that there was no slave rising during the civil war.

HASTIE: You're contrasting that with the slave risings before the civil war.

[00:08:31] Q: Here's a golden opportunity, and there was none.

HASTIE: Well, I suspect, I don't know, I'm not a sufficient student of that period of history, I suspect running away was substantially easier during that period, than before. So many of the able bodied whites had gone away to war, those who remained were preoccupied with so many essential things directly or indirectly related to the war, society was in a stage of some disorganization. So I would suspect that the statistics would show, if they were kept, and again, they probably weren't kept very well during that period, that the escaping of slaves was much more extensive and possibly there being that safety valve, that you could run away, it was easier to run away, than to stand and revolt.

[00:09:36] Q: Have you read, Judge Hastie, a book by Stanley Elkins, called Slavery, it came out three years ago.

HASTIE: No, unfortunately I haven't.

[00:09:47] Q: I wish you had, I'd like to have your views on that. It's a very interesting book.

HASTIE: Well, do you want to summarize his point of view.

[00:10:06] Q: Well, I think might do it violence by doing that, oh, I could summarize it, or indicate in a way, by referring to a remark by a Negro psychiatrist with whom I've talked, he regards, from his perspective, of the present movement, as a discovery of the male principal among Negroes. After centuries of matriarchy, and the loss of the full range of meaning by the male principal. Does that make any sense to you?

HASTIE: Well, I suspect it's an extreme oversimplification, but like most oversimplifications, it has, it has some kernel of truth in it. But I doubt very much if I could make any meaningful comment upon it.

[00:11:17] Q: It's not really fair for me to offer a sentence like that, I suppose, and carry a long argument behind as to its actual meaning. Let's turn for a moment to Myrdal's scheme, for what would have been, according to him, a good and fruitful reconstruction policy in the south, after Civil War. I'll outline that in a few strokes. One, compensation to southern Slaveholders for the emancipated slaves. Two, expropriation of land in the south, to accommodate the freed men, but compensation to the landowners for the land. Three, the distribution of land, but not his guilt, on some long range basis of payment, plus supervision and protection against sale and so forth, a lot of stuff like that. Then, some shifting of population, free land in the west, and so forth, some actual population shift. How do you respond to these proposals? Do you think they make sense?

HASTIE: Well, taking them in reverse order, I think the population shift, or the organized population shift, probably would not have been too important a factor. The south wasn't that badly overcrowded, and there unquestionably would have been considerable voluntary population movement in any event. The preceding items in Myrdal's catalog, represent a program for giving the Negro an economic start and a basis of individual independence, while at the same time, giving the ravaged south as a whole, some economic stake for moving forward again, through the device of compensation for property. I have no doubt that those things would have been useful. However, I have what I suppose would be regarded as a more radical view. I have a, the idea that if the reconstruction could have been continued another ten years, with some basic decency in the effort, without program of that sort, that very great and constructive changes would have been accomplished. I take two contemporary examples. The administration of Germany, and the administration of Japan. After the second world war, it is not a pleasant or an agreeable thing, to a community, or section that has been vanquished in war, to be under the domination of the victors and have the victors' will imposed for a period of time. But if it's done with decency and respect for the community, there can be, I believe, a radical change of community outlook and ideas and orientation, of society, even though the circumstances for that change are imposed by the will of the victor, and through an administration that is not democratic, or responsive to the will of the vanquished. So, my speculation, and of course, it can only be speculation, is that a decently and fairly administered reconstruction, under the will of the victors, could in another ten years, have accomplished changes in the society, that would have avoided what we are going through now, 75 to 100 years after the ill-fated reconstruction.

[00:16:49] Q: Did you feel that the period from '65, to '76, a great sell-out, was a decent and fairly administered program?

HASTIE: Truthfully, I don't know, and I don't say that to evade it. I am, I sometimes doubt whether it was any less decent than government generally in that day and time. We, history has preserved the record of many excesses that certainly were not decent, and I think, has tended to either not discover or not publish, the many constructive changes that were taking place. The beginning of free unsegregated public schools in South Carolina, for example, with about roughly half of the students white, and half of the students colored, in communities that had had no free public schools of any sort, before. I just have the feeling that we have not yet had, perhaps now the evidence is not to be found, and perhaps we never will have a truly objective appraisal of the reconstruction.

[00:18:18] Q: Would you feel any emotional resistance, looking back 100 years, to the compensation of slave owners, for the freeing of their "property"? The property being men.

HASTIE: No, I don't feel any emotional reaction to it, perhaps what I said before, would indicate that I think of it as just one of the possible devices, of subsidizing a war torn and disrupted economy.

[00:18:56] Q: A Marshall Plan.

HASTIE: A Marshall Plan, and the device being, or the measuring stick, being a compensation for the loss of slaves. It might be done without that, just as grants available to everybody for machinery and seeds and what not, but the, perhaps the compensation for slaves, is a rationalization, that would have made it more successful than if it had been done as an act of charity, so to speak.

[00:19:30] Q: Well, this all comes from that learned Swede of course, it never would have occurred to anybody in the north, of the Mason Dixie Line.

HASTIE: I believe there were many suggestions of compensations. I think Lincoln made some suggestions of that sort.

[00:19:44] Q: The radical Republicans. ?

HASTIE: Of, surely. This was also part of the the whole speculation – if Booth had missed, what course would the Reconstruction have taken.

[00:19:58] Q: Lincoln would have been impeached before the two years, before his term was up maybe.

HASTIE: Maybe, and yet, as the victor in the war, as the victorious war president, he might have had such a prestige, countrywide, that impeachment wouldn't have been feasible.

[00:20:20] Q: Did you see any irony in the fact that the March on Washington, wound up at the Lincoln monument, taking Lincoln's attitude on race?

HASTIE: No, I don't see any irony of it, because whatever Lincoln's actual views might have been, Lincoln today is to America, and to the world, the symbol of the goals of the March. So recognizing Lincoln's utterances before he became President, and in the days of his presidency before that Emancipation Proclamation, it does not seem to me ironic that one can find in an examination of Lincoln's utterances, many things that are contrary to the symbolic figure of Lincoln that we have built.

[00:21:32] Q: Actually, after the Emancipation Proclamation, one or two of his most positive statements on race was made.

HASTIE: That's true. My cutoff day is wrong.

[00:21:47] Q: In otherwords, you take this in his symbolic role, rather than his role as a human being, a prisoner of his times, is that right?

HASTIE: Yes, I think his importance to us today, is that of symbol, rather than as he may in fact have been.

[00:22:16] Q: What about Thomas Jefferson? The same sort of thinking.

HASTIE: Well, I'm not sure what aspect of Thomas Jefferson you mean.

[00:22:29] Q: He was a slave holder.

HASTIE: A slaveholder, who favored the progressive emancipation of slaves, unquestionably.

[00:22:40] Q: He also regarded the Negro as inferior being.

HASTIE: Oh, I

[00:22:49] Q: His actual quotes are quite standard racist quotes. Take a look at the Declaration of Independence. Now there's a play on in New York, off-Broadway, a sort of a dramatized reading of statements about race, and Jefferson comes off very badly.

HASTIE: Yes.

[00:23:08] Q: You see, as part of ironical or satyrical device, to have the great men saying bad things on the race question.

HASTIE: Right.

[00:23:18] A: As a piece of dramatizing, propaganda. This, but you prefer to leave him as a symbolic role, is that it, without presenting this other historical fact, about him.

HASTIE: Well, I don't say I prefer to do it, I say that whether it be Lincoln or Jefferson, the community acceptance of the individual as a symbol of something very wholesome and worthwhile is itself useful, and the fact that the individual in his life and utterances may not have measured up to the symbol, doesn't make me wish to reject the symbol and all the value that I think is in it.

[00:24:15] Q: What should a historian do, though, if he had to write a life of Thomas Jefferson? Or an essay on Thomas Jefferson's views, can you simply refurbish the symbol, and leave these other things out, how do you relate them, how should you relate them? To each other.

HASTIE: I'm not sure that I can answer that. You're saying, I suppose you're suggesting that history should not be written with any preconceptions of the concepts that will emerge, that if it is so written, it isn't history, but is historic fiction. If I were writing historic material about Jefferson or Lincoln, I would feel a moral compulsion, to put down what my research disclosed. In the case of both of them, I think the historic data would bring out an overall influence of the man, in his times, in accord with the present symbolism of the man.

[00:26:04] Q: You would take the historic perspective, the relevance of history then, and the chance of climate of opinion in human possibility, as a criterion, is that right?

HASTIE: Oh I should think so.

[00:26:16] Q: Of course some people don't. They want to keep the symbolism clean.

HASTIE: Yes.

[00:26:22] Q: How do you feel about a man like Robert E. Lee?

HASTIE: Well, I, I suppose we go back to Lee's fundamental decision, as to whether his greater loyalty was to the nation, or to his state and section. I, his decision, as to where his loyalty lay, is one that I greatly regret. Once he had made that decision of course, he followed the course of a great military strategist, and a very decent human being. Now your question may relate more precisely to that, and if so, follow it up.

[00:27:19] Q: He was an emancipationist. He freed his slaves, before the war, and you have the strange situation, of the leader of the southern army being an emancipationist, while Grant held a few slaves all the way through. What kind of ethical price tag do you put on these two facts?

HASTIE: Well, again, history emphasized the part of the person's conduct that had the greatest impact upon society, the thing that I first mentioned, that Lee's decision to throw, Lee’s decision to cast his lot with the south, was the thing of far reaching consequence, as distinguished from his personal views and his personal decisions, as far as his emancipating his slaves.

[00:28:22] Q: Can we distinguish the ethical and the practical consequences in his decision to stay with Virginia?

HASTIE: Can we distinguish the ethical and the practical consequences.

[00:28:37] Q: He presumably chose to do what he thought was right. What he thought was right, is not what you think is right. There's the practical consequence of defending something he didn't believe in, in part anyway.

HASTIE: You're saying we can, can we respect, do we respect a man for a decision based on personal judgment, of a higher morality that transcends his national allegiance. I suppose we can. If we do, of course, as in some cases we do, we respect treason.

[00:29:26] Q: How do you feel about ____________ view of the American Constitution and the American Union,

HASTIE: Which quotation, I'm not sure,

[00:29:37] Q: The trouble with death, and the cause of this union burns the constitution, and is covered with death, in league with death and in covenant with hell. That equals Lee in a little more violent language. How do we deal with that one?

HASTIE: Well, I should think, the legalist has to deal with it, in the same way. Again, Garrison's statement, is a truly revolutionary statement, as is Lee's position, a revolutionary position. You

[00:30:17] Q: Lee was a conservative of course.

HASTIE: Yes, but both are refusing to accept the national legal order. They are defying the legal order, and therefore they are taking a revolutionary position. Again, they both preached treason, though in one case one may agree or disagree, as the case may be, with the objective or the basis position of the individual.

[00:30:53] Q: Do you regard Garrison, as a higher ethical creature than Robert E. Lee?

HASTIE: I don't know. Frankly, I never made the, I’ll put it this way, I think Garrison was an intemperate person, and Lee was not. Garrison was probably the type of person who translated into the military arena, would have been a wonderful person, to lead a charge into the face of enemy guns. But probably not the person to be the commander of an army. There are certain stages when persons like that represent the spark to a movement or to a cause and we can recognize their value as that, without having a necessary admiration for the intemperate, even violent personality, yet we recognize that throughout history, those personalities, have been catalysts of great changes, some of them good, and some of them bad.

[00:32:29] Q: In other words, put ourselves outside of history, and say a little bit of salt and pepper, a little bit of evil in temper, a bit of salt and pepper makes the stew.

HASTIE: I think so.

[00:32:39] Q: But we don't make ethical judgments that way, do we?

HASTIE: Oh, no, no, we don't make ethical judgments that way, no.

[00:32:46] Q: Do you remember what Garrison did after the Civil War, his view toward the whole question of race and reconstruction?

HASTIE: Again, be more precise.

[00:32:58] Q: Well, he was, sort of lost interest in it when the war was over. Put it that way, withdrew from it, by and large, didn't care much what happened to the Negroes, you see.

HASTIE: Well, again, that's, that may be typical of a certain type of personality, the personality that leads the charge against odds, but could not handle the logistics of supplying an army. And it may well be that that that is the explanation in the personality of the individual.

END OF TAPE TWO

CollapseTAPE 3 Searchable Text

Collapse[These digitized texts are based upon 1964 typed transcripts of Robert Penn Warren’s original interviews. Errors in the original transcripts have not been corrected. To ensure accuracy, researchers should consult the audio recordings available on this site.]

JUDGE HASTIE

TAPE THREE

[00:00:14] Q: Does that little remark from Mr. Evers carry any conviction in you?

HASTIE: It does. Hearing it, made me think of something I don't remember who first said it, or if I ever knew who first said it. The quotation that comes to my mind – nothing that the white man can give the Negro is as important as the respect he withholds. Now that is important I think both for the Negro's reaction and for the white man's reaction. The Negro's resentment of particular situations is certainly underlain by his resentment of the respect that is withheld. And so many of the acute situations would not be acute, if the Negro has the feeling of being genuinely respected. Many of the demonstrations which, to some people, may seem pointless, or at least misdirected, I think and here I am playing the psychologist – are expressions of a inward urge to do something that both helps one's self-respect and wins respect from other people. So, from the Negro's point of view, and from the point of view of his white neighbor, I think that as the Negro wins the white man's respect, regardless of fondness or affection, it becomes easier for the two to deal with each other on a meaningful and constructive basis.

[00:02:10] Q: That is, the Negro's seeking of identity in the personal sense, is also connected with his seeking of a social identity, is that right, to put it in other language.

HASTIE: Well, I'm not sure which is personal identity and which is social identity. Spell out what you mean.

[00:02:32] Q: All right, I was think his sense of self-respect as his personal identity.

HASTIE: Oh yes, yes, in many ways, perhaps are opposite sides of a coin.

[00:02:43] Q: Yes, I should assume that they were. But they go together, then.

HASTIE: I think they do, unquestionably.

[00:02:51] Q: Let us take this line of speculation for a moment, let's assume that a perfect civil rights bill has been passed, is drawn and passed, with teeth in it; let us assume the Fair employment practice things are in operation and are enforced; let us assume we have integration of schools as far as, as practical, forgetting these extreme problems. What remains to be done, and who's responsible for doing some of the things that are to be done.

HASTIE: Well, the basic thing that remains to be done, is to develop a community in which men within themselves regard race and color as a matter of no great consequence. That would be my brief answer to your question.

[00:04:24] Q: Now what responsibilities would the Negro have in this?

HASTIE: He would have to seek a deal with his fellow men as individuals, rather, than as white men and black men, just as the white person would have the same responsibility. The Negro would have to come out of the protective shell, the habit of generations of living, which could impel him to seek in his whole range of community relationships, people of the same race or color, because there is no question that today you find many situations in which members of the white community are willing to meet Negroes more than half way, in human relationships which generally ignore race, yet find Negroes not responsive.

[00:06:03] Q: How much is that a problem of what we might call de facto inferiority, rather than any race inferiority as such? How much is that problem, a problem that has not been faced, by and large, by Negro publicist, or leaders, or society in general?

HASTIE: How much is there a problem of de facto inferiority that has not been faced?

[00:06:35] Q: As a responsibility of the Negro to face.

HASTIE: Oh, there is certainly is a very real problem of developing both social attitudes, personal pride, ambition, all of those characteristics that lead an individual to make as much as he can of himself individually, and as a useful member of society. There's much of that that has to be done, and a substantial part of the burden is on members of the Negro community themselves.

[00:07:32] Q: This goes back, I suppose, to the old split between the Booker T. Washington approach and that of Dubois, and that whole switch from "self-improvement' as a watch word, to right and power, watch words.

HASTIE: Some of it is the hen and the egg dilemma. It is much harder to work effectively for self-improvement, when the dominant pressures of society, are such as to convince the individual that he is not capable of very much self-improvement. So, I think that Dubois was right in recognizing that from the very beginning, there had to be major emphasis, on status and recognition and community acceptance, because without some substantial measure of those, the other drive doesn't go far. I realize some people would reverse that and say that it is much easier to win acceptance if the person demonstrates that he is worthy of acceptance. I think part of Dubois' dealing with that, was his concept of the "talented tenth". Many of the Abolitionists, had the same idea, that the goal could be achieved through a representative number or minority of Negroes, so demonstrating their fitness for acceptance that people would come to realize that denial of acceptance should not be a racial thing.

[00:10:00] Q: You see things like this, for instance, speech by James Baldwin, which I heard in Washington, at Howard University Nonviolent Conference last fall, -- "The lowest Negro drunkard or dope pusher has no reason to feel apologetic to any white man." Now this is an oracular pronouncement that probably means nothing excepting an attitude of a certain sort, self-improvement kind of thing. Denying

HASTIE: I understand that statement being made, but to me, it's meaningless statement. Of course, he has no reason to be apologetic to any "white man", but he has reason to be apologetic to himself, and to society.

[00:10:54] Q: And in a way, to other Negroes.

HASTIE: Of, of course.

[00:11:00] Q: Very definitely, would you say?

HASTIE: Yes, yes.

[00:11:02] Q: I noticed in a speech by Dr. King, more recently, that he wound up with a shift to the self-improvement theme, very emphatically – "If you are a street sweeper, be such a street sweeper that the angels in heaven will bend over and say "what a street sweeper we have!." Now this is the old, this sounds like Booker T. Washington, you see, back to the laying down your buckets where you are. A whole swing, you see, back, to that.

HASTIE: I'm not sure that it is, because I think every school or every leader in one way or another, tries to drill and stimulate pride in his followers. And I don't think that this is an earmark of one school, rather than the other. The Black Muslims' pride in blackness is part of their thesis.

[00:12:09] Q: And self-improvement too.

HASTIE: And self-improvement also, yes. So I don't believe that's a distinguishing characteristic between schools. It may be that the distinction is that Booker Washington had a tendency to make that almost a whole program, as distinguished from one feature, of a program having other major aspects.

[00:12:43] Q: But there seems to be, I don't want to speak as if I had any, made a survey of this, but the notion of self-improvement has become almost disreputable, in certain circles, because it seems to give something away. The propaganda.

HASTIE: Are you speaking now of the contemporary scene, or are you speaking historically?

[00:13:11] Q: Well, both, both. The emphasis has shifted the other way, and, but it's maybe my sympathy with Dubois, you see, I think we have to be on that. The question is now a little different, of whether the self-improvement idea, has now taken on a symbolic value, which is a negative, where it seems to imply time, process, delay, you see, becomes a bad word.

HASTIE: I see, yes. Certainly a large part of Negro leadership is suspicious of the emphasis on self-improvement by those elements of the white community which are thought to be disposed to slow down the drive for equality. On the other hand, I suspect that it would be hard to find any significant Negro leadership which in dealing with the members of the Negro community themselves, did not place some substantial emphasis on self-improvement.

[00:14:35] Q: Somewhere, in fact, in the last book, James Baldwin says that the best testimony is that the southern mob does not represent the will of the southern majority.

HASTIE: It may be that it doesn't represent the will of the southern majority in the sense of procedure, but in the sense of maintaining the status quo, or preventing any major shift in racial etiquette and accommodation, I wish I could feel it did not represent the will of the majority. But in 1964, I'm afraid it does. Of course, we go back 25 or 30 years and find that prevailing sentiment in the south, came to disavow lynching as a horrible crime, but that did not mean that the dominant will was against keeping the Negro in his place, it was merely against keeping him in his place in that particularly horrible and shocking way.

[00:16:11] Q: What about the northern will to keep the Negro in his place?

HASTIE: Well, I think unhappily there's more of that will than we sometimes like to recognize. I think I expressed to you earlier my fear that the 25% vote for governor Wallace in the Wisconsin primary, truly represents a 25% opposition in your so-called liberal northern communities to some against changes in the status of the Negro – for example, unsegregated or free access to residential neighborhoods, and numbers of other aspects of segregation.

[00:17:16] Q: I read a report on the Gallup Poll about northern attitudes, a few weeks ago, recent poll, I mean, recent in a matter of months, on public accommodations, the sentiment, northern sentiment ran very high, say 75% in favor of, you know, free access to public accommodations, no discrimination.

HASTIE: Yes, I would think it might even run higher.

[00:17:42] Q: Or even higher, as given then, about 75-80, maybe 80%, it's high anyway. The other, right with it, "would you consider leaving your neighborhood of a Negro family came in?" It ran almost as high, would seriously considering leaving it – or would do so. About 55.

HASTIE: That doesn't surprise me. In fact, if I had given detail in answer to one of your other questions, as to what has to be done, after there is the needed legislation, I would have said that one of the basic indexes of the change of sentiment in which people become indifferent to race is attitude towards living in the same immediate neighborhood with Negroes. And I have the feeling that that is the, perhaps the last of the major community problems to be solved, and perhaps the most difficult.

[00:19:07] Q: Is it possible that it would be easier to change in the south than it is in the north?

HASTIE: I heard that same from time to time, and there is of course, some historic basis for it. Urban residential segregation on a broad scale, is the product of your restrictive covenants and your comparable practices, in the development of northern cities, largely in the period between the first and second world war. And during that period, there were many southern communities, in which a relatively few Negro families who were economically in a position to live in a better neighborhood or who happened to own property and lived for a few generations in that neighborhood, lived quite peaceably with white neighbors. Now, whether it is easier today, to get persons in the south to change that pattern, than in the north, I don't know.

[00:20:46] Q: You find this strange thing, an extremely bright young Negro lawyer in New Orleans, complaining to me that they had no ghetto. This is a political defect.

HASTIE: In New Orleans.

[00:21:01] Q: They have no concentration of votes, you see.

HASTIE: New Orleans is an atypical city, because of its whole historic background, of Creoles, people of mixed blood, and even of anti-segregation legislation that was on the Louisiana statute books, but ignored, 30-40 years ago.

[00:21:33] Q: It's true too in other southern towns, to a degree, the interlocking of neighborhoods, and overlapping of neighborhood, was regretted by a very modern-minded young man, who would like to have his ghetto as a political device, you know, to break the ghetto.

HASTIE: Yes.

[00:21:51] Q: It gets funny, doesn't it?

HASTIE: Yes, I think of one of the very early public housing projects in 1930's in one of the South Carolina cities. I've forgotten whether it's Charleston or Columbia. Even in those early days of public housing, there were those in Washington in the national organization, who were making some effort to set up public housing on a nonsegregated basis. In this particular South Carolina city it was finally agreed, that the new housing project would be a long narrow area, between two parallel streets, with an alleyway running parallel to and between these streets. The houses facing on street A would be for Negroes, the housing facing on street B would be for whites, and there would be a common alley separating them. The people could, as they did, visit over their back fences, but formally they would conform to a pattern of residential segregation though it really was not a meaningful separation, in the community life.

[00:23:20] Q: What about the fact that there's a tradition, not a tradition, but just a fact of long standing, of personal association. That's a, that never crosses the mind, I presume, or any Negro or any white man, in the south, as something unusual. Personal physical association.

HASTIE: Yes.

[00:23:44] Q: There are associations of all kinds.

HASTIE: Yes, association is entirely acceptable, so long as the etiquette of the superior group and the inferior group is respected.

[00:24:02] Q: Now what about the reverse in the northern mores, there's no etiquette involved, but simply a refusal of association, or withdrawal from association.

HASTIE: Yes.

[00:24:12] Q: If the etiquette is changed, and segregation changes an idea and etiquette is changed, the spadework you might say, of the personal association, some people maintain, has already been done in the south. It never had to be undone, it was always there, in some way, in all kinds of ways.

HASTIE: Yes.

[00:24:32] Q: From fishing trips to bedroom, it was just always there.

HASTIE: That's probably true, but it doesn't minimize the difficulty of the problem of changing the attitude.

[00:24:46] Q: No, no, no, people are gonna get shot over that.

HASTIE: Yes.

[00:24:49] Q: No, I didn't mean to make that easy, but I'm thinking, I'm looking forward, to another stage. This line of speculation is that some people would hotly deny that it makes any sense at all. Some people say yes, it's a factor to be considered of importance. I'll read you a quote if I may, maybe I'll change the subject a little bit. "The whole tendency of a Negro History Movement, not history, but its propaganda, is to encourage the average Negro to escape the realities, the actual achievements and actual failures of the present. Although the movement consciously tends to build race pride, it may also cause Negroes unconsciously, to recognize that group pride is built partly on delusions, and therefore may result in a devaluation of themselves, for being forced to resort to such self-deception." This is from Arnold Rose, Myrdal's collaborator.

HASTIE: Yes.

[00:26:05] Q: I might save time for you if you would puzzle my writing if you wish, you're a judge a long time, so you can hear things.

HASTIE: That seems to me to presuppose a sophisticated analysis of history contrary to common experience, whether one is dealing with a Negro or with any other person. I doubt whether the reading of such history, has much broader consequences than the intended consequences referred to, namely, stimulating a sense of some measure of pride, rather than shame in one's race and background. I don't think that the reading of such history, tends to make people believe it is unimportant to try to improve themselves. I just doubt whether in actual experience, that consequence is realized.

[00:27:39] Q: I would offer this as a piece of evidence. I would offer the evidence, of southern history, southern official white history, where it's the old south, you see, offers an official view of themselves, of ourselves, you see, by their white confederate southerners. And this, as recognized by many, many, many people, still cling to this idea, even they know it's a fraud, they are passing themselves, and they feel sort of uncomfortable about this. When you hear to it, you break out of it, you see. But I recognize the human possibility, because I've seen this thing working for white southerners.

HASTIE: Perhaps that has an aspect

[00:28:27] Q: Self-delusion.

HASTIE: What Mr. Rose said had an aspect that I did not grasp at the first reading of it. It may have the effect of giving an excuse for being as I am. I have been mistreated, I have been taken advantage of, and therefore the responsibility for my improvement is exclusively the responsibility of those who have mistreated me. If that is what was meant, I certainly can see an element of truth in it. Is that the view that you think is being expressed?

[00:29:18] Q: Well, I think that's part of it. I think there's another part, if I make it out, again by analogy. Of you could go to the extreme case of the Black Muslim history, the false history, the fabricated history, to justify pride. But it just has to be that false, to use history as a substitute for a present reality and to build a pride which is outside of rational justification. I think the southern myth, the white verandah, and the julip and the contented darkie plucking banjo and cavalry charges, instead of the historical south, as we gather from real history. A myth, a delusion, a dream, which is used to justify some sense of superiority, or defect, as you say, in other words, it can work both ways. In the south it works both ways, justifies the alibi, as well as consolation.

HASTIE: Well, insofar as Negro history is used to attempt to inculcate in the Negro the idea that he is a superior person as contrasted with just another human being like other human beings, of course, it's bad. I don't believe that there has been too much impact, even among the black Muslims or the Garvey movement, in convincing Negroes that they are members of a superior race. But to the extent that there has been that effect, certainly it's unwholesome.

END OF TAPE THREE

CollapseTAPE 4 Searchable Text

Collapse[These digitized texts are based upon 1964 typed transcripts of Robert Penn Warren’s original interviews. Errors in the original transcripts have not been corrected. To ensure accuracy, researchers should consult the audio recordings available on this site.]

[00:00:24] Q: I'll read you another quotation, related. "If Negroes are to claim the past, that is rightfully theirs they will have to assume the risk that go with the past. Acquisition of a past is necessary, but also pericous, for it means an end to innocence. Just as the Negro past shows beauty and grandeur, so it also shows human meanness, cruelty and injustice. The Europeans after all, did not invent the slave trade. They stimulated a commerce that Africans had carried on from time immemorial" and so on. Now you find occasionally this, say Lomax, one of Lomax's books, when the white man went to Africa, to seize the slaves, he tells part of history, but not all of it.

HASTIE: Yes, part of the economy of tribal war, was to seize the vanquished adversary and sell him into slavery, unquestionably.

[00:01:27] Q: But the whole picture, do you recognize this problem of a risk of the past in a new self-consciousness of Negroes, of their history, sometimes, they may recognize the risk.

HASTIE: Perhaps I don't recognize it as much as I should, because in my limited perspective, I think we are so far short of developing a really great pride of African ancestry. Also, I think that since during the generations of slavery, the slaves were torn away from that tradition, and tradition is not something one builds with a few books. I don't see how a great danger of the Negro developing an arrogance of race. I think the likelihood is that he develops increasing desire be assimilated in American culture, as distinguished from an arrogance as African. And if I am right about that, while the possibility is there, I don't believe the danger is a very great one.

[00:03:54] Q: Outside of the Black Muslims, of course, that small group.

HASTIE: Oh yes.

[00:04:00] Q: You raise a question the, that is very important, to some Negroes, at least some tell me this is important to them, the question of a tension, a split in the psyche, which Dubois wrote about quite often – between the pull toward, you know, what is now the African mystique, or Negritude, or, even the Negro tradition in America, as distinguished from Western European culture, the Christian, the Judeo-Christian tradition, or Americanism – a real split, which was for some, like Dubois, was a real problem, a fundamental problem, which he never resolved until the very end, I was told. And for some people, as some people now say, this is a real problem, I'm torn. There is the risk of losing my identity in the white race, the white culture, or my grandchildren losing their identity in the white race, in the white culture. Is this significant to you, may I ask? Do you feel it's an issue?

HASTIE: I think it's an issue, perhaps I see it in somewhat different perspective.

[00:05:10] Q: Well, please, please tell me about that.

HASTIE: I see this building up of a pride in blackness, a special pride in African tradition, as filling a vacuum created by a sense of denial of a sharing in the pride of contemporary America, in the history of our own country. And I have a feeling that as Negroes increasingly have an opportunity to really feel that they are a part of America, and the American tradition, that their preference will be to that source of pride and identification. I think you can now observe that in the increasing group of young Negroes who are having, first, educational opportunities, and economic opportunities, outside of the Negro community itself, and who take pride in their American identification, but without any sense of shame, because of their racial identification.

Now I realize that there are all too many who still don't have such opportunity. With many of them this special pride in race, and in racial background and tradition, may well serve as an essential thing to the building of the ego. But I believe it will be a this need for and use of "Negritude" will be much less 50 years hence.

[00:07:41] Q: There's some tendency, among various, you might say, types of Negroes, as far as I can make out, I am told, to resent the shall we say, Negro success, that is, the Negro who makes a professional or business or intellectual success, and and is not officially committed to some program of militant development of Negro position. The most recent instance of this, is the attack on Ralph Ellison because he has kept on just being a novelist, though his novels are certainly clear enough, in terms of his attitude, his novels, not the story, apart from, you know. Well, you see what I mean, this, resentment.

HASTIE: I see what you mean, yes.

[00:08:39] Q: Resentment from the uneducated and the poor, and the deprived, on up through people who have elected to be officially Negro militants. This is not enough to make it personal, I mean, a person like you is outside of that, or a person like a Negro scientist or Negro doctor or Ralph Ellison, who stand outside of official organizations devoted to Negro advancement. This special kind of leadership from the outside, from the periphery, from personal achievement, which is repudiated by certain Negroes quite violently. You no doubt have encountered in certain ways. How much of a problem is this, do you think this has real significance, or just ordinary little human _________.

HASTIE: I have several comments. First of all, it's not peculiar to the Negro. There is resentment in the overall society, and I think properly so, directed toward the individual who has been personally successful in an economic way, and does not have an active concern for the problems of the disadvantaged. So, in that aspect, I think such resentment is inevitable and I share it. Similarly, Negroes who are disadvantaged, resent Negroes as well as, perhaps more than, whites who have achieved personal advantage, and are not willing to devote of their time and effort and to helping their disadvantaged brothers. On the other hand, whether we are dealing with Negroes, or whites, or any groups, there inevitably is a certain amount of human jealousy, of success. And human jealousy is reflected in overt resentments of various sorts. Both of those aspects, I think, are real and important.

[00:11:53] Q: The question of betrayal is a little bit different again. The person betrays his obligation to fight for, you know.

HASTIE: Yes. There certainly have been and still are some Negroes, who use their positions of some eminence or success to persuade their brethren to be patient, to recognize that in God's good time wrongs will be righted, and so on. Some Negro during the days before the abolition of slavery, I think, came out with the expression "Be still and kiss the rod," – that sort of advice. That has always been resented, always will be, and I think, always should be resented. In some cases, it's sheer selfish personal advantage seeking by people who feel that they can improve their own position, in the society or the economic community by by indicating to whites that they can exercise an effective restraining influence upon other Negroes. But the interesting change in the Negro community, in the last 20 years, certainly, is that very few Negroes, feel that they can effectively maintain that posture, because they become so quickly and outspokenly disavowed by Negroes generally, that they are no longer recognized in the white community as being able in some measure to control the Negro community.

[00:14:29] Q: Can't deliver the vote any more.

HASTIE: No, so you find the most conservative Negroes today, taking public positions far more outspoken than what Negroes who were considered radical 30 years ago, would then take.

[00:14:46] Q: Some are forced into and some sincerely accept it.

HASTIE: Correct, correct.

[00:14:53] Q: What lies behind a thing like Dawson's trouble in Chicago? He's a politician of long, long success.

HASTIE: I don't know, I'm far removed from the Chicago scene, though at one time I knew something of it. I suspect there are numbers of things. There comes a time in any dominant one-man, or small group, political control, when people, including perspective leaders, become restive and want to throw off that control. There's also the fact that throughout this period of Congressman Dawson's political dominance in Chicago, many Negroes have seen aspects of their community life and position getting worse rather than better. So this may be a rejection of leadership which, in a broad social view, is seen as having failed.

[00:16:14] Q: Let me read a little card of questions – There is the danger that the the danger that the new found militancy, Negroes may become the victims of their own rhetoric. Negro leaders have already shown a tendency to react to labels, rather than substance. Once a proposal is called soft, or moderate, one feels obliged to attack without regard for the merits of the case. In the fall of 1963 many Negro leaders attacked Kennedy for opposing the "strong" and supporting the "weak" version of the Civil Rights Bill, put before the House Judiciary Committee, yet the strong version was in some ways much weaker, when called strong. For example, it omitted the creation of a Federal registrars to insure Negro voting rights. And so on.

HASTIE: This tyranny of labels and characterizations that analytically don't mean what they say is, I think, characteristic of all social struggle. It's characteristic of political struggle. If one succeeds in giving a particular label that has a bad connotation to a candidate, that candidate loses votes, even though analytically and in fact his position does not deserve that characterization. Therefore it becomes a test of the skill of leadership, to avoid as much as possible the adverse labels, and to win the socially attractive label, to its program.

[00:18:22] Q: We're back to symbolism again, in that way.

HASTIE: We're back to symbolism again. In the American scene, one of the striking examples of success in maintaining a liberal image is provided by the leadership of Puerto Rico, the party headed by Governor Munos Marin, which has been in power through 20 years or more. This group has managed to maintain the popular image of itself, as forward looking and uncompromising, while carrying forward a statesmanlike program opposed by a vocal extremist minority which has called for independence now and has denounced present leadership. There is a problem of social and political tactics here that is very difficult and sometimes very worthwhile leadership has been impaled on a slogan or an _______.

[00:19:56] Q: You know the various interpretations of the phrase – the debt to the Negro – this notion that in its most extreme form, it's payment in back wages, now many people take it that way, you see. For how many hundred years. In other forms, Mr. Whitney Young's notion of a crash program for the underprivileged Negro. And the other form of course, if the question of preferential treatments, in various ways.

Now how can we distinguish any level of this notion of the debt to the Negro, from the debt society owes to any underprivileged person, who is also underprivileged, say in the Harlans of Kentucky, now, in the coal, the dead coal country of West Virginia. How do we, can we distinguish, this one kind of debt from the other and if so …..

HASTIE: Logically, I think we can't. We cannot analytically make such a distinction. The Negro is perhaps the largest identifiable national group as to which this concept is conveniently applied. Also, this debt concept relates to 100 years of slavery, which, in the public mind, a special kind of debt, because it relates the most grievous sort of deprivation. I think basically, again, here is something that is a useful symbol, in social struggle. But as a real justification for a particular program, I would certainly concede that there is the same justification for a program of assisting any and all of the underprivileged in our society.

[00:22:30] Q: Some people go so far to see nothing but danger in a preferential program, for Negroes if it ignores the needs of other poor and underprivileged.

HASTIE: Well, danger, I'm not sure.

[00:22:50] Q: In building up resistance.

HASTIE: Oh, in building up resistance in the white community.

[00:23:00] Q: Particularly among the poor underprivileged whites.

HASTIE: Yes, yes, well, there's certainly, let's take preferential hiring. That particular thing. There certainly is a grave danger, in preferential hiring, in a static or contracting economy. I doubt whether there is a grave danger in any economy that's expanding as rapidly as ours is, and hopefully is going to be, say, in the next decade. The, if our total unemployed labor force employable unemployed labor force, is say, substantially under 5%, while the underemployment of Negroes is very much higher, I don't believe the social impact of preferential employment for Negroes, on the white impact community as a whole, is going to be serious. Now, I'm not speaking of the morality of it now, or of the justification, but I'm talking about how people will react to to it. And in that respect, of course, I must agree with those who feel that the expanding national economy, the rapidly expanding national economy, is a fundamental thing, in any program of improving the economy of the Negro within our national order.

[00:25:00] Q: Quota and preferential treatment are quite different, though, in the application even in a contracting economy, or stagnant economy aren't they? You can justify quota approach, but you can't justify preferential, is that right?

HASTIE: Well, I'm not sure that the two are different except in degree.

[00:25:22] Q: They're different in degree because we …..

HASTIE: A quota is preferential, but it's limited preference.

[00:25:31] Q: It's preferential only if the Negro is not as well equipped for the job, though, isn't it?

HASTIE: Right.

[00:25:40] Q: If he's well equipped.

HASTIE: The unspoken premise of what I was saying, is that for reasons that we need not detail now, we are going to have the problem of large numbers of Negro applicants for employment who in one way or another, are not as well equipped as many white applicants. Some of these Negroes will be adequately prepared for certain training and employment, yet not as well prepared as some white competitor. In this situation, if we pass over the number one person in the group of those who can adequately do the job, in favor of the No. 2, or the No. 20, to achieve preferential scheme of Negro employment it is unfair to the No. 1 man. And the No. 1 man and others are unquestionably going to have resentment such preference. But in the expanding economy, that problem may not be acute, if only because there is going to be opportunity for most capable people, regardless of race.

[00:27:38] Q: Anyway, they'll make it.

HASTIE: Right.

[00:27:43] Q: That's a tough question, though, isn't it, tough problem.

HASTIE: Oh, it's a very tough problem, and unquestionably, there will be a bad reaction in the general community, if the impression is abroad that what the Negro wants, is not justice, but opportunity beyond his merits.

[00:28:18] Q: Merits more or less, merely accidental personal merits, based on his misfortunes of the past, even. Aside from the economy, the problem of maintaining or developing an expanding economy, at a greater rate than we now have it, one of the big things is simply program of training, education and training, isn't it, for both the whites and Negroes?

HASTIE: Oh, of course, it is.

[00:29:06] Q: New technology for one thing.

HASTIE: Surely.

[00:29:09] Q: But that gets mislaid in a discussion, very often, doesn't it?

HASTIE: Yes, but I think it is being increasingly realized in the Negro community. For example, here in Philadelphia, headlines are being made by a small but rather ambitious project, sponsored by a large group of Negro ministers and assisted by the Chamber of Commerce and business leaders. For a privately developed program of training for industry Negroes who, at the present time, lack the skills for the jobs that are available. And while the size of the program is not yet such as to make real impact on city wide Negro unemployment, it does represent a major emphasis, originating in the Negro community, upon this aspect of the problem.

[00:30:26] Q: How well are you acquainted with, what is it called, the Woodlawn Project in Chicago?

HASTIE: I really know it only by name, very limited reading.

[00:30:46] Q: Afraid we are winding this up.

END OF TAPE FOUR

JUDGE HASTIE, APRIL 20

Collapse